Did you know that the central aspect of patriarchy isn’t female subjugation?

Did you know that the central aspect of patriarchy isn’t female subjugation?

Some of you may be surprised to hear me say that, given my focus on how patriarchy (especially Christian patriarchy) subjugates women. Don’t get me wrong. Female oppression lays at the heart of patriarchy, but it is more a consequence of patriarchy rather than the focus of patriarchy. The central aspect of patriarchy is men. Or, as sociologist Allan Johnson explained in The Gender Knot: Unraveling our Patriarchal Legacy, “a society is patriarchal to the degree that it is male-dominated, male-identified, and male-centered,” which means that “core cultural ideas about what is considered good, desirable, preferable, or normal are associated with how we think about men and masculinity.” Women are valued in patriarchal societies for how they relate to and support men. They are typically not as valued for their independence from men.

I still remember when I finally understood this. I had spoken up in my women’s history seminar that night. I don’t remember our exact words, but the conversation went something like this:

The other students in the room wanted to know why Southern Baptist women defended their own oppression. Some were puzzled; some were angry; and I was irritated. I was still a Southern Baptist, and—even though I was uncomfortable with complementarianism—I didn’t consider myself oppressed. So, I spoke up. “I don’t think Southern Baptist women consider themselves oppressed, at least not all of them” I said. Let’s just think about Dorothy Patterson. She wears a hat as a symbol of her outward submission, but it doesn’t cover the significant power she wields throughout her conservative world. She teaches (preaches?) at Baptist seminaries, in Baptist churches, and at Baptist convention; she publishes books read throughout the Baptist community; and she was supported by her husband and community to get her PhD. I doubt she considers herself oppressed.

The professor had been watching us. I can still see her sitting at the head of the table, holding one of the oranges she had brought to the class for snacks. “Let’s think about why that is,” she said. Pulling out a small knife she began to quarter the orange, waiting for us to speak.

“Maybe women don’t feel oppressed because it works for them,” someone finally said.

I don’t remember who said this. I don’t remember if these were the exact words (although they are close). I only remember how it silenced me. Indeed, it hit me like a slap to the face. Maybe some women don’t feel oppressed, even within a system that oppresses women, because it works for them? Because, even if the system is male-centered, women as supporters still feel valued and important. I knew this wasn’t the whole story. Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere, (most?) evangelical women believe in female submission because they believe it is what the Bible teaches.

(As one insightful reader of this original blogpost pointed out, so many women living within complementarianism have little choice because it is their entire church and family culture. For many women, there is not a viable alternative. This is absolutely true. For many other women, though, complementarianism is just the backdrop of their lives. It provides identity, community, and purpose. It validates choices they have made and even opens doors for leadership, jobs, writing opportunities, etc. Like any other social structure, complementarianism impacts people differently. By discussing the benefits of complementarianism for some women I am not intending to be dismissive of women’s theological beliefs nor to imply that all women benefit from it.)

Could part of the story of why some women support complementarianism also be because it works in their favor? Because it rewards women who play by the rules?*

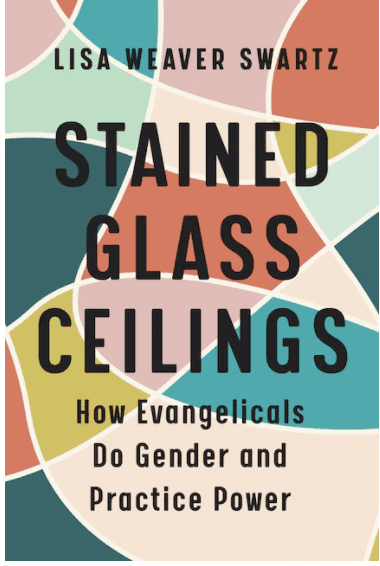

In her brilliant and forthcoming book, Stained Glass Ceilings: How Evangelicals Do Gender and Practice Power, Lisa Weaver Swartz argues that women’s empowerment within evangelical institutions “is available to the degree that [women] are willing and able to cooperate with the constraints of an institution whose identity is built around male-centered stories,” (212). Women who play by the rules are more successful. As Swartz writes, “the most successful church women adapt. They learn to display just the right amount of femininity in public, navigate the demands of the second shift, and resist developing structural critiques or feminist consciousness.” In exchange for limited agency, they gain “legitimacy and voice,” (189, 221-222). Patriarchy does not center women; but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t value women. Plus, when evangelical women’s voices support and enhance the voices of men, they are more likely to be heard. You will have to wait till Swartz’s book releases at the end of this month for the rest of her argument, but believe me when I say she helped me understand part of the answer to that question asked in my graduate seminar—why do Southern Baptist women support a structure that subordinates them?*

In her brilliant and forthcoming book, Stained Glass Ceilings: How Evangelicals Do Gender and Practice Power, Lisa Weaver Swartz argues that women’s empowerment within evangelical institutions “is available to the degree that [women] are willing and able to cooperate with the constraints of an institution whose identity is built around male-centered stories,” (212). Women who play by the rules are more successful. As Swartz writes, “the most successful church women adapt. They learn to display just the right amount of femininity in public, navigate the demands of the second shift, and resist developing structural critiques or feminist consciousness.” In exchange for limited agency, they gain “legitimacy and voice,” (189, 221-222). Patriarchy does not center women; but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t value women. Plus, when evangelical women’s voices support and enhance the voices of men, they are more likely to be heard. You will have to wait till Swartz’s book releases at the end of this month for the rest of her argument, but believe me when I say she helped me understand part of the answer to that question asked in my graduate seminar—why do Southern Baptist women support a structure that subordinates them?*

Because it works for them is at least some of the answer for some women. Maybe not consciously for most women; certainly not for every woman; but both evidence and experience suggest it is true for some women. Complementarianism provides a space created by and for women that is supported by men. As Swartz shows so well, it gives women community, acceptance, assistance, education, identity, and legitimacy. If they stay within the predefined boundaries (i.e., not wielding authority over men nor resisting male authority), complementarianism even supports women in ministry. Complementarianism, like all patriarchal structures, does not center women. But, because it needs women, it values women who help keep it going.

(Just so you know, Swartz also helped me understand the lack of empowerment for women within so many egalitarian structures. As I wrote in my endorsement, “In a brilliant and compelling narrative, Lisa Weaver Swartz shows how patriarchy persists and adapts even in spaces supportive of women in ministry. Her research explains why women defend complementarianism as well as why the gender-blindness of egalitarianism fails. Regardless of your theology, you should read this book. I promise it will help you better understand the plight of evangelical women.”)

But what about the women who don’t play by the rules? The women who don’t fit the complementarian narrative. Well, they have a harder time. Historically speaking, they are also less likely to be remembered. Swartz writes how evangelical institutions “erase” non-conformists from collective memory, retelling or just forgetting the stories of those who “do not align” (63).

Take, for example, Bertha Smith. She isn’t discussed by Lisa Weaver Swartz, but she fits the description of what happens to the stories of non-conformists within evangelical institutions. Just last week a friend asked me if I had heard of her. The question surprised me. I put down my grilled pimento cheese and provolone sandwich (I promise it is good). The clock was ticking on our conversation. We had approximately 40 more minutes before my friend needed to be back in his classroom.

“The name sounds familiar, but I’m not sure.” I answered honestly. “Who is she?”

Olive Bertha Smith was a Southern Baptist woman who preached. Indeed, the reason my friend (a pastor) had known her name was because she had preached at his church. But, like me, most of his congregants didn’t remember who she was. Growing up in the post-conservative resurgence Southern Baptist world, I knew the name of lots of famous Baptists, like William Carey, B.H. Carroll, Billy Graham, Adrian Rogers, Oswald Chambers, Martin Luther King, Jr., John Bunyan, W.A. Criswell, Charles Stanley, and (although I hate to admit it) Jerry Falwell. But, aside from Annie Armstrong and Lottie Moon (the namesakes of the two major Baptist missionary offerings), most of the names I knew were men. I had never heard of a woman preaching in the Baptist world.

Which meant I’d never heard of Bertha Smith.

I’d never heard of how she felt called by God to ministry, graduating in 1916 from the Woman’s Missionary Union Training School in Louisville, KY. I never heard how she became a Southern Baptist Missionary in China in 1917, serving in the Shantung Province and becoming a part of the great revival there alongside Baylor alumna C.L. Culpepper. I didn’t know that she was imprisoned by the Japanese during WWII, expelled from China by the Communists, and appointed the first Southern Baptist missionary to Taiwan, serving there until she retired at the age of 70.

I also didn’t know that she preached the Sunday morning service at “hundreds of Southern Baptist Convention churches during her lifetime,” especially between 1958 and the early 1980s. Indeed, you can find both audio and video of Bertha Smith’s sermons on the internet today. Just check out these posted by Greater Cleveland County Baptist Association, or here on sermonindex.net. I didn’t know that Bertha Smith influenced Baptist leaders like Charles Stanley and Adrian Rogers, urging both to run for president of the Southern Baptist Convention, and that she even preached at Adrian Rogers church. How ironic one of the men responsible for the Conservative Resurgence, which pushed women out of the Baptist pulpit, was influenced to take leadership because of a woman who had preached from his pulpit!

Bertha Smith was an international missionary, prayer warrior, and preacher. Yet when Daniel Akin preached a sermon in honor of her at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, guess which of her ministries he did not emphasize? Entitled “Bertha Smith: A Soul-Winning Missionary and Woman of Prayer, Revival and the Victorious Christian Life,” he intersperses portions of her life with scripture and quotes from male preachers, including complementarians like Tim Keller, Tom Schreiner, and John Piper. He describes her ministry as one of sacrifice, prayer, and “personal witness.” He emphasizes that she, as a woman on the mission field often did “the work which men do not go to do.” He quotes her description of the mission (church?) she built in China: “Miss Smith Baptist Mission,” which she wrote on a sign and placed on a bamboo fence. People began to come, she wrote, and—“in addition to the Sunday services, we had Bible classes Tuesday and Thursday evenings.” She was an evangelist and a prayer warrior, but he doesn’t describe her as a preacher. He also doesn’t mention that she spent more than 20 years at the end of her life preaching from the pulpit in Baptist churches and teaching Baptist pastors like Charles Stanley and Adrian Rogers.

I still have a lot to learn about Bertha Smith, including reading her memoir and digging in to the historical records from her life. But I can tell you that Bertha Smith–no matter how her life is framed–taught adult men, preached Sunday morning services from behind the pulpit, and exercised authority over male leaders in the Southern Baptist world. Wade Burleson is right to be angry about Al Mohler’s amnesia over women preaching. As he writes to Mohler, “You are as old as I am, and you probably listened to Miss Bertha teach us the Word of God in a church, or from a Southern Baptist Convention platform.”

When I learned about Bertha Smith last week, I couldn’t help but think about that question asked in my graduate seminar, especially in light of Lisa Weaver Swartz’s forthcoming book. While I can’t speak for all complementarian women, I can speak from my experience as a complementarian for more than twenty-five years (1990-2016), and I can speak from the evidence of history. So, why did I as a woman support complementarianism for so long?

Because I believed it was true.

Because, as Lisa Weaver Swartz has found in her research, it gave me identity and purpose.

And–because women like Bertha Smith had either been omitted from my education or recast to “align” with the values of my complementarian world–I didn’t remember anything different.

*Citations for Lisa Weaver Swartz are from the page proofs. I will update as soon as I receive the published book.