I will never say that progress is being made. If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. The progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even begun to pull the knife out, much less heal the wound. They won’t even admit the knife is there. – Malcolm X, 1964

The absence of brutality and unregenerate evil is not the presence of justice. To stay murder is not the same thing as to ordain brotherhood. – Martin Luther King, Jr., 1967

Perhaps one of the most significant things that I have learned as a historian is that racial reconciliation is a myth. For this to make sense, however, one must understand the three constitutive elements of that statement: race, reconciliation, and the role of myth.

As I’ve hinted in past pieces, race is not a neutral construct. It is a particular historical one. Whiteness, blackness, Asianness, indigeneity and other such terms are often flexible and stretched by their uses rather than their Platonic forms. This is why Jonathan Tran and others focus less on what race is, a conversation that could occupy much of our time with little tangible effect on the lives of our brothers and sisters, and focus more on what race does: that is, the tangible ways that the construction that we call race shapes our lives. By “the myth of racial reconciliation”, I mean this story that we tell ourselves: that if we just get people with different racial identities together in a room or if we just build more extensive and diverse friend groups, racial disparities will fade and racial injustice will cease. After all, no one wants to be racist…right?

It is unfortunate that there are still Christian circles that latch onto this language because it is, at its root, less than Christian. I know and respect many dear brothers and sisters who use the language and justify it, but I personally cannot. This is not to say that the language of reconciliation is sub-Christian: reconciliation lies at the heart of the human being’s relationship with God and her fellow human beings. But when one appends race to the term, it loses its historical significance. Reconciliation with God and reconciliation with your neighbor assume prior peace broken by sin and later restored. When we talk about race, we are talking about a concept whose very root is exploitative. What is sub-Christian about the term is that it obscures the historical reality that there is no relationship to restore. Rather there are wounds to heal, modes of domination to dismantle, and methods of exploitation to resist. Such an idea is summed up in my favorite sentence of one of my new favorite books, as Jonathan Tran explained Cedric Robinson’s term “racial capitalism”:

Racism helps set the conditions of domination necessary for capitalist exploitation, just as exploitation in turn elicits the justification that, under conditions of domination, racism provides…the process of exploitation produces [racial] distinctions.

Martin Luther King, Jr. said it this way:

It seems to be a fact of life that human beings cannot continue to do wrong without eventually reaching out for some rationalization to clothe their acts in the garments of righteousness. And so with the growth of slavery, men had to convince themselves that a system which was so economically profitable was morally justifiable. The attempt to give moral sanction to a profitable system gave birth to the doctrine of white supremacy.

Order is supreme. Exploitation and domination precede justification. Race has always occupied the latter position, which is not an ideological claim. It is a historical one. The other issue that this draws attention to, however, is the fact that even if the ideas were to fade, the dominative and exploitative conditions would continue. Yes, I want my brothers, sisters and neighbors to think well of me, perhaps even love me. But that is a tall order. I will settle for them not having the power to kill or exploit me with impunity. As a friend of mine wrote in a short article, you can’t relationship your way out of racial capitalism.

For example, when people frame the phenomenon of racialized lynching, the picture that often consumes the American mind is that of crazed mobs of thousands of white men, women, and children in a bloodthirsty frenzy killing a Black man, whether by hanging, burning alive or by shooting him to pieces. It is emotionally preferable for us in the twenty-first century to hear of this history and to maintain a comfortable historical distance. But we can only do so if we think of racism in terms of frenzied violence. Ida B. Wells saw past the frenzy, at the time justified by Southern apologists as the acts necessary to protect Southern white femininity. Wells saw the truth, however: lynching was a weapon to maintain white hegemony. It was how white communities “kept the Negro in line”, present yet subordinate. In post-Reconstruction America, where some still had the memory of slavery, the exploitation of Black labor continued. Violence was one of the tools necessary to maintain that exploitation.

So why did lynching fade? Did southern whites just become less violently racist? Sociologists Stewart Tolnay and E. M. Beck answered this question at the end of their insightful book, A Festival of Violence:

We are not naïve enough to believe the white elite experienced a revelation that exposed the “evil” of prejudice, discrimination, and racial violence. Rather their transformation was much more pragmatic and self-interested. They witnessed the exodus of the very population that provided their supply of cheap and pliant labor.

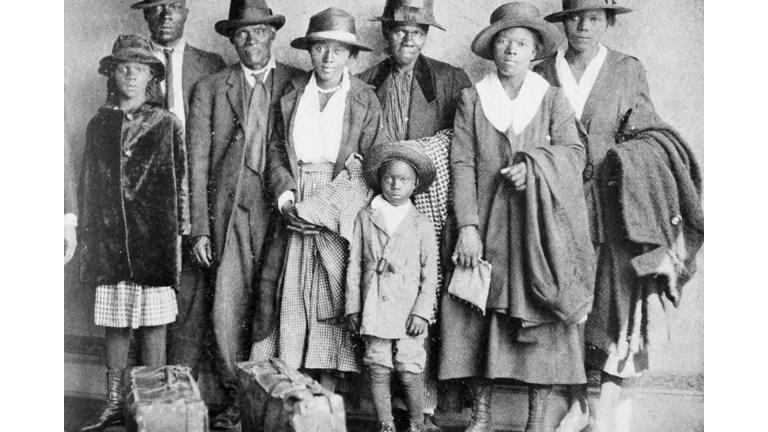

The Great Migration paired with the bad press that lynching began to get in the 1920s and 1930s both nationwide and internationally ultimately best explain the decline of spectacle lynching. In summary, lynching faded because it became a threat to the political economy of the South, not because people stopped being racist. In fact, this should be a conclusion that we expect if racialized thinking is, as it has historically been, post facto justification of exploitation. Reconciliation did not stop the brutal deaths of Black men and women. What Ida B. Wells named “the white man’s god” had to be threatened: the wallet.

This then narrates the root of the issue with racial reconciliation language. At no point in American history has there been the active presence of “racial peace” or “racial justice.” As long as race has been a conversation and category, it has been a category of exploitation and of division. Even as we move forward, we cannot single mindedly seek the eradication of harmful ideas without also spending time, political energy, and money alleviating the material conditions that kill and exploit. Some will be upset that I do not here go into the ways in which we have progressed: after all, slavery has been abolished! (No, it hasn’t been. Our prison system is, constitutionally, slavery.) Spectacular anti-black violence like lynching has stopped! (No, it hasn’t. The spectacle just takes a different form, like police killings on social media.) One can approach this with two minds: self-congratulatory pats for lessening brutalities that never should have existed in the first place or relentless seeking not for the absence of brutality but for the presence of love and justice.

This brings us back to the direction we ought to look when we ask and answer questions about race and how it works. It is good for us to love one another as Christ has commanded us, but that love must take the form of recognizing the political economy in which we live. Race and the systems of domination and exploitation it has propped up have left waves of devastation and death in their wake to the extent that even in their seeming absence, the wounds remain. The segregated cities, housing, and schools remain. The poverty maintained by what Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor called “predatory inclusion” remains. The conditions that attempt to make it impossible to properly love our neighbor remain and impose themselves on our minds as “normal”. We cannot let that imposition remain. Slough off the myth that racial justice will be achieved if we, through interpersonal relationships, reconcile. Our ethical imaginations must always tend not merely toward survival, but toward liberation and healing. Pull the knife out, treat the wound, and walk and heal alongside the wounded, understanding that the way forward is not to accept the world, but to seek and await its remaking that began at the Cross and will soon be completed. That will be a political economy in which we thrive.