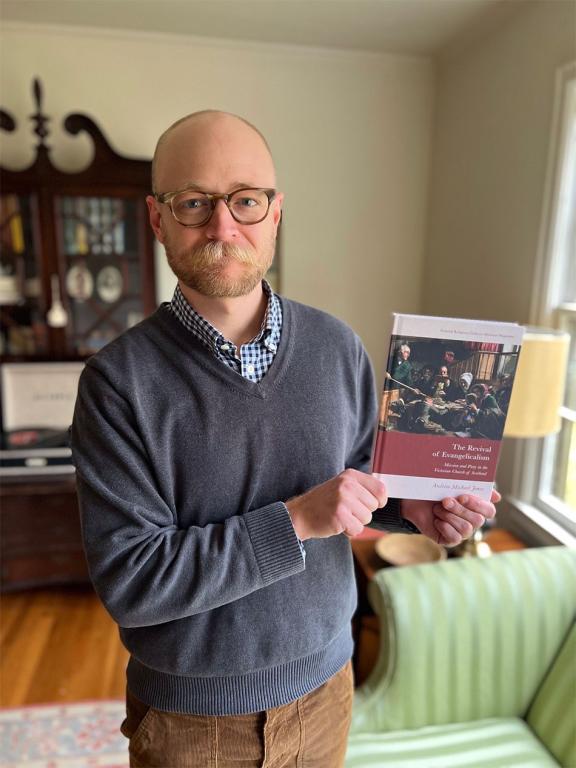

Today we have the pleasure of featuring a guest post from Andrew Michael Jones. Andrew Michael Jones is the NEH Postdoctoral Teaching Historian at Reinhardt University in Waleska, Georgia. He completed his PhD at the University of Edinburgh and published his first book, The Revival of Evangelicalism: Mission and Piety in the Victorian Church of Scotland, with Edinburgh University Press in 2022. He lives in Marietta, Georgia—on the southernmost edge of the former Cherokee Nation.

While I’ve spent most of the last decade as a historian of religion in modern Scotland, this academic year I accepted a postdoctoral fellowship near my home in the metro Atlanta area that focuses on the Cherokee Nation. The specific remit of the project is to transcribe, digitize, and provide interpretation for hundreds of claims against the U.S. government made by members of the Cherokee Nation from what is now the state of Georgia, where I grew up and moved back after wrapping up my PhD in Edinburgh.

In May of 1838, the men, women, and children of the Cherokee Nation were rounded up, forced from their homes, dispossessed of the vast majority of their belongings, and placed in concentration camps to await their removal to Indian Territory, according to the stipulations of the fraudulent 1835 Treaty of New Echota. Between this period and the beginning of what later became known as the Trail of Tears, agents working for Principal Chief John Ross went around the camps and took claims for property from the Cherokee people. These 1838 claims provide a treasure trove of information about Cherokee life before removal, the process of removal, and the people involved. Critically, they also amplify the voices of a story so often told through the lenses of white missionaries, soldiers, and politicians.

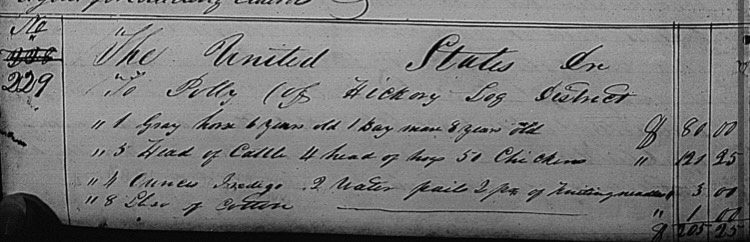

I’d like to share two examples of stories I’ve found thus far embedded in the 1838 Cherokee claims. The first (#229) is the experience of a woman recorded simply as Polly (it was not uncommon for Cherokee people to lack European-style surnames in certain contexts). Relating to the theft of some horses and cattle:

Claimant states that a white man known to her by the name of Ned came to her house and forcibly took off her horses and claimant has not got her horses since. [S]aid man is a citizen of the United States. [T]he cattle was stolen in the year 1833. The claimant states that she was from the home and a whiteman by the name of Waggoner came and killed claimant’s cattle in presence of her children and she has not received any compensation for the same.

The second (#736) shows the extent of the property taken from some of the people in question. In this one, a man named Jack Still claims five houses, a corn crib, stables, an apple orchard, a peach orchard, a plumb orchard, and 70 acres of “good river bottom land” on the Chattahoochee River.

The only crime both claimants committed was being born Cherokee. Yet they lost nearly everything, in often dehumanizing and violent ways.

What these individual stories and the broader story of removal have in common is what my friend Malcolm Foley recently discussed here at the Anxious Bench as prototypical racial violence. According to Foley:

There are three profoundly important things to remember about this violence: first, that it is and has been constant; second, that it is more often linked to political and economic dominance than it is to hate; and third, that there have always been voices that have resisted it.

What I’d like to offer now are some reflections on how each of these three facets of racial violence relate to the history of the Cherokee people, with specific reference to Cherokee Removal. Along the way, I’ll provide some resources for those interested in learning more.

First, the pressure to claim Cherokee land in Georgia dates back to the colonial era, but became much more constant following the so-called Compact of 1802, whereby the state of Georgia ceded its western land claims to the federal government with the promise that the land would be cleared of indigenous peoples in due course. By the second and third decades of the nineteenth century, this had not been accomplished and the white people of Georgia grew restless. Bands of white horse-thieves – like those that stole the livestock from Polly – terrorized the Cherokee Nation while Georgia legislators began to extend state jurisdiction over the Cherokee Nation and parcel out Cherokee property to “lucky drawers” in a state-sponsored land lottery. The pressure faced by the Cherokees divided their leadership, causing a minority to agree to a treaty whereby they would cede all Cherokee Nation lands in the east for a financial settlement and other lands west of the Mississippi River in present-day Oklahoma. An excellent recent study of the way in which state and local violence presaged the run-up to the Trail of Tears is Toward Cherokee Removal: Land, Violence, and the White Man’s Chance by Adam J. Pratt.

Second, the forces that eventually caused the mass removal of the Cherokee people in 1838 were driven by avarice and power as much – if not more than – a unique antipathy towards the Cherokees, as such. Did they consider members of the Cherokee Nation equal to them despite their darker skin? No. Did the fact that a non-“white” people group existed in the South in a free-yet-secondary class deeply trouble the racial hierarchies of the plantocracy? Yes. However—as Claudio Saunt’s Unworthy Republic has recently shown—the plot to dispossess the Cherokees (and Chickasaws, and Muscogees, and Choctaws, etc.) and access their cultivable land for growing a cash crop (“king cotton”) involved Georgia politicians as well as financiers in New York and Europe.

Third, there were people throughout the era of Cherokee removal that resisted, both members of the community and white allies. The fact that thousands upon thousands of Cherokees resisted is extraordinary, but not at all surprising. They were fighting for their birthright, a land that they held sacred. More damning to the argument that the white people of the time simply “didn’t know any better” is the fact that many white Americans also protested the Georgian-Jacksonian collusion that eventuated removal in the end.

The person I find most compelling who fits this second mold is a man named Evan Jones (no relation). Jones was born in Wales, but emigrated to the U.S. and became a Baptist missionary among the Cherokee people of modern-day North Carolina. He saw fruit from his evangelization efforts, not least through the conversion of the future Cherokee Baptist icon and Cherokee Nation political leader, Jesse Bushyhead. In 1984 the Brown University historian, William G. McLoughlin (1922-1992), wrote a wonderful account of the complex interactions between the Cherokees and Christian evangelists called Cherokees and Missionaries: 1789–1839. In it, he recalls the ways in which Jones resisted throughout the period, and eventually chose to accompany his flock along the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma.

Finally, another quote from Foley’s piece: “I am convinced that the formation of a just society, a goal that many United Statesians will claim, requires a just appraisal of and reckoning with the past.” That reckoning for people like me means both staring the past in the face, honestly, and then, with humility, reconsidering the stories we tell about ourselves. White Americans, at least in my experience, like to think of ourselves as the heroes or central actors in the story of American history. Yet our, or at least my, ancestors were often the villains that dispossessed the inhabitants of the good land, ploughing under fields of green corn and planting cotton to be picked by enslaved Black persons, carted off to Savannah, and shipped to Liverpool for the sake of mammon.

Casting ourselves unilaterally as protagonists in the narrative of American history is both ahistorical and morally corrupting. Moving forward in the life of our nation, may we all receive the grace to choose the narrow gate of the Jesse Bushyheads and the Evan Joneses of the world—one of sacrifice, justice, and true Christian witness—over the wide gate taken by the Georgia legislators and federal agents.