Disclaimer: I want to offer a short warning which could hypothetically go alongside most of my pieces. The following has rather graphic descriptions of lynchings in American history and the accusations that accompanied them, which included brutal murders and sexual assaults.

There are a few things that every United Statesian should know about racial violence in the United States. The shame is that this is a history that has been actively suppressed for a while, though I have been encouraged in the last few years to see the popularization of some of it in the last few years. Yet I am convinced that the formation of a just society, a goal that many United Statesians will claim, requires a just appraisal of and reckoning with the past. For those in this country, that requires a robust reckoning with a history of racial violence. There are three profoundly important things to remember about this violence: first, that it is and has been constant; second, that it is more often linked to political and economic dominance than it is to hate; and third, that there have always been voices that have resisted it.

The first thing to note is that such violence is constant and deeply embedded in this nation’s history. As I reflect on the violence of Indian Removal, Chinese Exclusion, slavery, lynching, and coups in Latin America and the Middle East, a question nags at me: how do any of us have any robust engagement with US history without emerging as deeply disturbed people? Consider, as Claudio Saunt does in his excellent book, Unworthy Republic, that “from the moment that the British set foot in North America, they began driving off Native residents” and that this not only amounted, in many cases, to mass murder but that it attempted to sever the connection between people and land, a connection that colonialism always seeks to sever. Consider that when lynching enters into the popular imagination, the rope is the most prominent image, but for those in the lynching era, the primary image was not the rope, but the stake. The spectacle lynchings of Sam Hose, Jesse Washington, Henry Smith and others bear witness to the brutality that human beings are willing to visit upon one another to maintain political and economic dominance. Yet that sheer brutality is also often shocking to those who first hear of it. Unfortunately such shock often reveals ignorance; this kind of violence was spectacular, yes, but not unprecedented. The way that Native Americans, Chinese and Mexican folks particularly have been treated not merely by individuals but by the United States government adds context to a history that is, in many ways, a history of profound and constant violence.

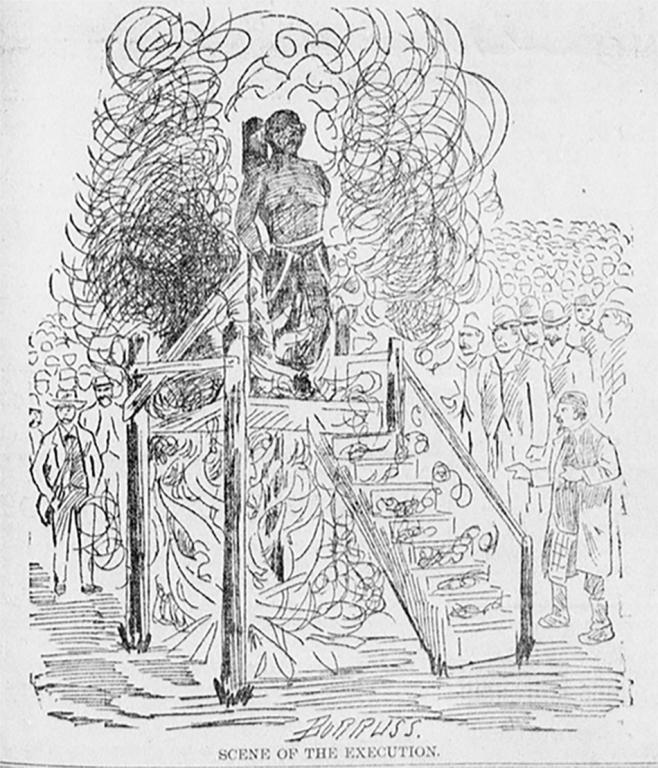

The second thing to keep in mind is that people rarely engage in violence for violence’s sake. These examples do exist, of course, but when we consider governmental and mob action, we have to consider more than just mindless thirst for blood. An example of the tendency to retreat to the latter can be found in the work of a 19th century bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church South. In Paris, Texas, on February 1, 1893, Henry Smith, who had been accused of raping and killing a four-year-old white child, was lynched. The mob applied red-hot irons to his whole body, branding him as well as running the irons down his throat before dousing him in coal oil and burning him alive. Haygood was called upon to “explain not the killing but the torture by burning,” by The Forum magazine, already an interesting request insofar as the killing was assumed to be easily justified. The torture was the anomaly. Haygood’s response, however, would cause Ida B. Wells to question his claims to Christianity. Haygood proceeded to say that he did not condone it, but he did understand it, saying:

Sane men who are just will consider the provocation. Sane men who are righteous will remember not only the brutish man who dies by the slow torture of fire; they will think also of the ruined woman, worse tortured than he. When they think of the infuriated mob in Paris, Texas, and the negro ruffian tortured most horribly till he was dead, they will think also of a white baby, four years old, first outraged with demoniacal cruelty and then taken by her heels and torn asunder in the mad wantonness of gorilla ferocity. Indeed the instant comment of a negro man to whom I stated this case was, “He ought to have been burnt.”

Much could be said about this quote ranging from the deeply problematic comparison made between sexual assault and burning someone alive to the instrumentalization of a Black man for the purposes of advancing an argument. What is most important here though is that this provides the ammo for Haygood to claim that the mob burned Smith because of temporary insanity, a frenzy precipitated by a particularly brutal crime. The “provocation” explained the torture.

Ida B. Wells, however, had a different account. Upon her research and reporting, she found people who bore witness to profound mental illness in Smith. She also found that the rumors of rape were unsubstantiated but rather added to reports in order to actually build a mob and make a brutal death all but inevitable for the accused. With this lynching and others, Wells refused to take the justifications of the lynchers at face value. This was not frenzy or hate run wild. Elements of even this brutal lynching spoke to the intentional targeting of marginalized Black people in order to either eliminate them or keep them in line. Wells’ summary understanding of the phenomenon, however, is best understood by interrogating the remedies that she suggested, the first of which was the withdrawal of Black labor from the South. As she noted in her pamphlet, Southern Horrors:

To Northern capital and Afro-American labor, the South owes its rehabilitation. If labor is withdrawn capital will not remain. The Afro-American is thus the backbone of the South. A thorough knowledge and judicious exercise of this power in lynching localities could many times effect a bloodless revolution. The white man’s dollar is his god and to stop this will be to stop outrages in many localities.

Wells saw what many refused to see: that the way to stop exploitative violence was to remove the occasion for exploitation. She saw in the lynching of African Americans the same thing present in the lynching of Mexican and Chinese workers and the killing of Native Americans: the thirst not for blood, but for profit and for land. It is thirst for the latter that continues to take lives today.

Lastly, one must constantly remember that resistance has always taken place alongside this violence. It is rare that I will suggest that one make assumptions about this history, but I am supremely confident in this one: if there is brutality of the sort that I have narrated above, there is also a contingent of human beings who recognize it for the evil that it is and who are compelled to act in light of that. My own research focuses on Black Protestants who resisted lynching in a number of different ways ranging from prayer to self-defense, but it was precipitated by this assumption: that resistance is always present. Some would likely prefer that resistance to be revolutionary, especially violent. Yet especially in situations where the oppressed were (and are) incredibly outgunned, much more creative modes of resistance are found. It is this third lesson that is the most relevant to us in this current moment. As we are faced with an age where the violence we face is often less spectacular, yet claims as many lives, we are also called to resist. When we consider the effects of carceral and police violence, the continued violence of a system initially meant to protect white property, we would do well to consider those who have suffered in our past and the ways that they continued to assert and maintain their dignity in a society that sought their death. Though the stakes may not burn in our midst, we have found other ways to kill one another. If we are to love one another well, we must discern and uproot such policies, practices, and processes that erode human life.