Happy Filipino American History Month, everybody! In honor of this occasion, I’m doing the one thing I love more than snacking on a freshly pressed polvoron: thinking and writing about religion, popular culture, and Asian American life.

The theme of religion and Filipino American life received a good deal of attention this year in the film Easter Sunday, which was released in theaters in August and is now available to stream. Starring the Filipino American comedian Jo Koy, this film chronicles the experience of a struggling actor who returns home to celebrate the Easter holiday with his loud and lovable Filipino family. Easter Sunday is probably the most extravagant celebration of Filipino American life I’ve ever witnessed on screen, with appearances by Filipino American celebrities (Lou Diamond Phillips, Tia Carrere, and Eva Noblezada!), multiple references to Manny Pacquiao, and assorted hijinks in the settings of contemporary Filipino American life: a mall in Daly City, a family karaoke party, and, of course, a Catholic Church.

To reflect on what Easter Sunday can tell us about Filipino American religious life, I assembled a group of Filipino American religious studies scholars and theologians to discuss the film:

- Rachel Bundang, PhD, Religious Studies faculty, Sacred Heart – Atherton and Pastoral Ministries adjunct faculty, Santa Clara University

- Gabriel Catanus, PhD, Director of the Filipino American Ministry Initiative (FAMI) and Affiliate Assistant Professor of Theology and Ethics, Fuller Theological Seminary

- Rev. Neal D. Presa, PhD, Visiting Associate Professor of Preaching at New Brunswick Theological Seminary and Affiliate Associate Professor of Preaching at Fuller Theological Seminary

Easter Sunday as “the Filipino Superbowl”: The Centrality of Religion in Filipino American Life

Melissa Borja

Early in the film, Joe Valencia, the main character played by the comedian Jo Koy, explained why he needed to return home to visit his mother. “Easter Sunday is like the Filipino Superbowl!” he said.

This statement is a controversial one. Without a doubt, Easter is a notable event in the Philippines. There, Lenten processions, Holy Week passion plays, and Easter Sunday rituals are elaborate affairs characterized by celebration and spectacle. Some events, such as the San Pedro Cutud Lenten Rites in Pampanga, even draw large crowds who witness penitents flagellate themselves with bamboo and volunteer to be nailed to wooden crosses. In contrast, while Filipinos living in the United States observe Easter, it’s not obvious that Easter is more important than Christmas or New Year or any time Lea Salonga performs in concert or a family member acquires a new karaoke machine.

But if we set aside the matter of whether Easter Sunday actually is the Filipino (American) Superbowl, the decision to make Easter Sunday the focal point of a film that unapologetically glorifies all things Filipino is a significant one. The film illuminates a vital fact about Filipino American life: Easter is a big deal to Filipinos because religion is a big deal to Filipinos. Put simply, a Filipino American movie about a family celebrating Easter Sunday reminds us that religion is central to Filipino American life and to Asian American life more generally.

A Pew Research Center report on Asian American religious life shows the remarkable religiosity of Filipino Americans. According to this report, 89 percent of Filipino Americans who were surveyed identify as Christian (65 percent as Catholic and 21 percent as Protestant), and among Asian Americans, Filipino Americans have the lowest percentage of religiously unaffiliated people (8 percent). 85 percent of Filipino Americans–a higher proportion than any other ethnic group–said that religion is “very important” or “somewhat important” in their lives. Finally, 56 percent of Filipino Americans surveyed reported that they attended church at least once a week–a church attendance rate that was higher than any other Asian American ethnic group.

The details of Filipino piety shared in the Pew report ring true with my own experience. I remember praying the rosary in the family minivan on the way to elementary school, hosting visiting priests who led novenas at our dining table, and listening to my parents detail their bus trips to visit historic Catholic churches throughout the country. Growing up in Saginaw, Michigan – a town with a relatively small Asian American population – I also recall how much religious life and ethnic community life overlapped. In Saginaw, there was no Filipino cultural center, no Filipino restaurant, and no Filipino grocery store. But we had the church, which functioned as the home of a vibrant Filipino American social club that gathered in the narthex after Mass every Sunday. Local titos and titas would hang around the holy water stoup to catch up with friends and discuss grandchildren, trips home to the Philippines, and expectations (usually dismal) about the upcoming Detroit Lions game.

I’ve long argued that we can’t understand Asian American life without understanding Asian American religious life. By making an intentionally Filipino American film that puts a religious event at the center, the creators of Easter Sunday emphasize how faith is a central feature of Filipino American life.

Gender and Generation in Filipino American Devotional Life

Rachel Bundang

Across multiple interviews, Jo Koy has made clear that among his major intentions in making Easter Sunday was to reflect Fil-Am audiences back to themselves and to assert Fil-Am representations in the wider US culture. While his portrayal is incomplete and imperfect, I appreciate his awareness of needing to go beyond artifacts (like the Santo Niño devotion) and accents (verbal and cultural).

Like any Fil-Am child who grew up Catholic here in the US, seeing the Santo Niño statue occupy a central place on the mantel was immediately familiar. Whether perched in a home or in a side chapel at the local parish, the statue underscores how central devotions and observances have been to Fil-Am Catholics for generations— often more so than sacraments. Also known as the Infant Jesus of Prague, the Santo Niño is, in many ways, like our Virgin of Guadalupe. He comes with that distinctly Spanish overlay, which for me recalls the countless conversations with other Fil-Ams over the years about the search for a decolonized faith and spirituality. Anecdotally, this has been especially true for the second generation onward: they may participate and identify culturally, but holding firm to a traditional Catholic religiosity as inherited is less important.

Along these lines, it was also interesting to notice how the labor of religion and spirituality was work left largely to the women of the first (immigrant) generation. As is so often the case, they are the guardians and transmitters of religious identity, beliefs, and practices, preserving the cultural threads and memory that survive. The extended family— subsequently Americanized—just came along for the ride and did what the matriarchs expected.

Even with our space constraints, let me toss in a couple more loose threads that we can perhaps weave into the larger roundtable. First of all, the nods to Daly City/Bay Area hip hop culture made me question again how Fil-Ams use proximity to both whiteness and blackness as markers of American identity for themselves. Given this, it was refreshing to see onscreen a fluency with multiple ways of being Asian American, taken as fact, with little explanation. Secondly, we’ve got Lou Diamond Philips as less a gangster figure than a callback to the guru in the cave— in his case, the garage— or a Mr. Miyagi type, offering guidance and a tangible link to a deposit of culture. Overall, we’ve got reminders to include religion as a primary lens for understanding Fil-Am and Asian American experiences.

Food and Faith in Easter Sunday

Neal Presa

In the 2022 movie Easter Sunday, we see the sibling rivalry between Jo Koy’s character Joe Valencia’s mother, Yvonne played by Lydia Gaston, and his aunt/Tita Teresa as they each try to outdo one another in the fiesta being prepared for the family. Underlying the competition is a need for the two sisters to reconcile, especially on the holy day of Easter. My roundtable colleague Dr. Bundag astutely observes that the “labor of religion and spirituality” was left on the shoulders of the two protagonist women in the movie.

In his book Filipino American Faith in Action, Joaquin Gonzalez of the University of San Francisco notes the central role of food to cultivate communal identity (kasamahan) through adaptation and accommodation, the “propagation and reinforcement of faith-based Filipino values,” connecting Filipinx migrants and their families to the Philippine homeland/parentland and our ancestors, and to rekindle a sense of home. Connected to kasamahan is the Filipinx notion of kapwa, which according to Filipinx psychologist Virgilio Enriquiez is best translated as “shared togetherness.” Kapwa, the mutual interconnectivity of Filipinos to one another (and to wider spheres, including country and the Earth) is central to Filipinx cultural and religious identity, for which food and the fiesta gathering are thick with meaning and signification.

The power of food at a Filipinx fiesta is in the sacred gathering of family, friends, neighbors and strangers; the sacred investment of love and care in food preparation, and the pride that the host/hostess have in bringing joy to all those partaking in the feast. It’s the setting of table that connects all those gathered to the holy Table in church sanctuaries, whose Host is the Holy One who welcomes all to the feast of thanksgiving, where reconciliation is made possible between siblings, among all of God’s children.

The next time you are invited to a Filipinx fiesta by a friend’s aunt’s neighbor’s grandma — come, enjoy, feast at the table that has been prepared, give thanks for the food and fellowship, bring your appetite, and bring your stories. You will be blessed as you encounter the Holy.

Power in the Gloves

Gabriel J. Catanus

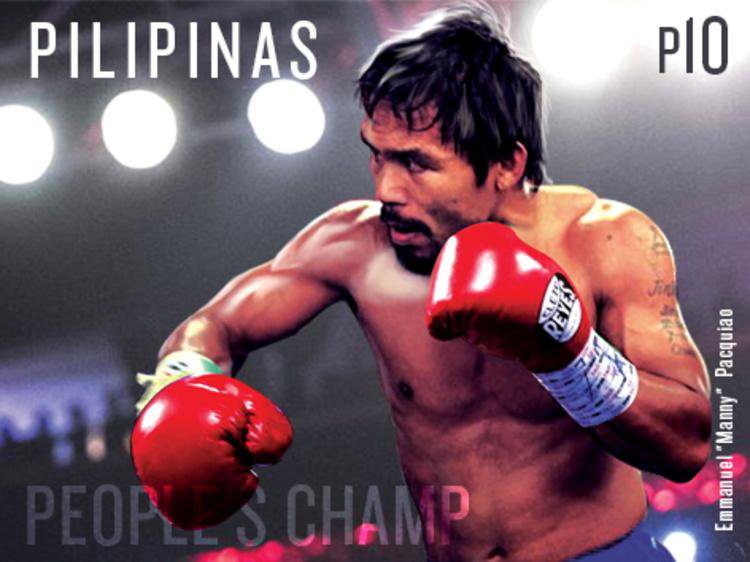

A few days before the 2015 Pacquiao-Mayweather superfight, I launched a blog site with an essay titled, “The Gospel According to Manny Pacquiao.” The gist was simple, based on Manny’s own words at the pre-fight press conference: “I came from nothing into something. And I owe everything to God who gave me this blessing.” The response to my blog post was overwhelming and telling: more than ten thousand hits and dozens of emails in less than two weeks! Though I’ve since taken down my blog posts and much has changed for Manny and the Philippines since then, his status among Filipino Americans— especially Filipino American Christians— was and still is unmatched.

It follows, then, that even without appearing in the cameo-filled movie, Manny and his legacy are a real presence in Jo Koy’s Easter Sunday. Fourteen years later, the boxing gloves Manny wore when he defeated (and retired) Oscar De La Hoya hold symbolic and sacred power for whoever possesses them. Dev Deluxe steals them, Marvin Ma can’t touch them, Tala knows about them, and Lou Diamond Philips pays a fortune to have them— so that, in Eugene’s words, they can be “liberated” from foreign control. When Lou tries them on, he actually “becomes” Manny (in Joe’s words).

In Easter Sunday, Manny’s boxing gloves function like Filipino anting-anting, amulets enabling their wearers to tap into supernatural power, especially during Holy Week— which is fascinating given the movie’s title, though it’s doubtful Jo Koy intended this. Filipino revolutionaries actually wore anting-anting when fighting against their Spanish colonizers. And by lacing up Manny’s gloves and having his own loób (inner or true self) strengthened, Joe is finally able to defeat the villain threatening his Filipino American family and identity. As Rachel points out, the Santo Niño (“Baby Jesus”) occupies a central place in the Filipino American Catholic home. But one can argue that the Christ-figure of Easter Sunday is actually Joe Valencia himself, as he suffers for his family, taps into the Filipino fighting spirit, and through it all finds himself.