This is me making a mea culpa, and actually profiting from the process. I made an error, and learned from it, and it sent me off on some really intriguing directions. As a result, I think I now have some important things to say about two of the great social, cultural and religious crises in human history.

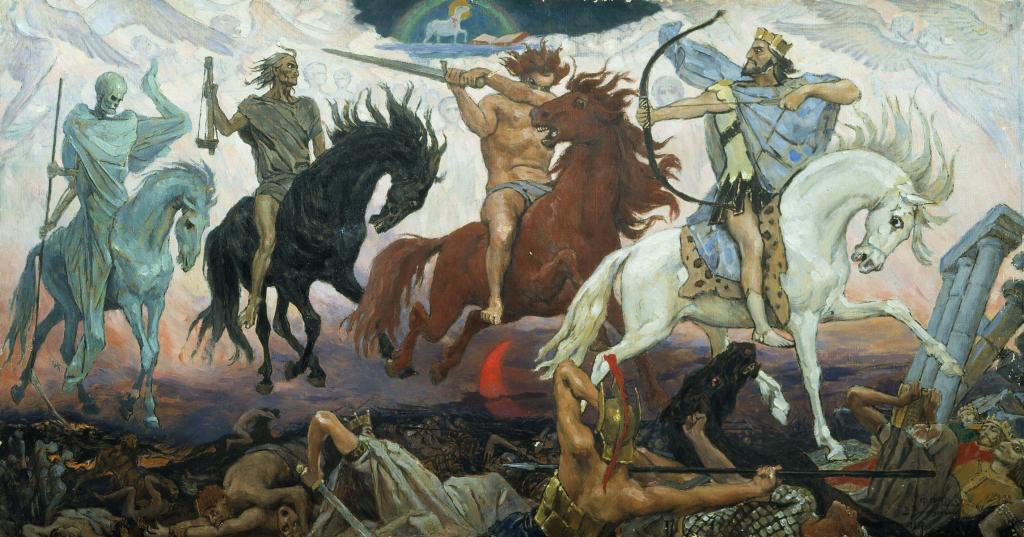

I work a lot on climate history, and the role of climate-related disasters in riving political and religious change. This was the theme of my 2021 book Climate, Catastrophe and Faith (OUP) and many blogposts at this site. I cite several particular times of singular catastrophe, marked by famines, plagues, and general social and political meltdown, to which people responded through “apocalyptic” understandings. In fact, as I have said in the past, one such era inspired the original apocalypse, namely the writing of the Book of Revelation under the emperor Domitian, in the 90s AD. Or so I believed, and now I think I am wrong.

So first, the mea culpa.

This period of the 90sAD has been an ongoing project of mine, but my argument will have to be amended or outright withdrawn. I have searched intensely, but am running into walls.

Reading the material in Revelation clearly suggested a meltdown of the sort that emerges so strongly in other eras, and which is usually associated with either an El Niño event, or more probably, a major volcano. The combination of famine and plague is very suggestive, and so especially are the comments indicating changes in the skies. The fit is excellent, to the point of looking like a textbook example. Something is happening.

I then set off to find supporting evidence, for periods where such documentation is scarce. Most of the usual databases don’t work, because of the very early date, but I can’t find records of a volcano or a super-cold event in any of the obvious resources, eg the bristlecone pine data which does produce such a textbook year in 43BC. There is the large Ambrym volcanic eruption of 50AD, and some third century candidates, but the dates are just wrong. Nor do I find obvious support in the well-studied reign of Domitian himself. I then turned to the excellent Chinese records, which offer the foundation for some fine examples of environmental studies, particularly relating climate to phenomena like desertification, harvest failures, and the sudden mass movements of nomads, not to mention the collapse of dynasties. The evidence is superb and consistent for such disasters as I am hypothesizing, but it falls almost exactly a century too late, anticipating the fall of the Han dynasty in 220AD.

I am simply not finding support for my statement about the 90s, and this is puzzling me. I must be wrong. On the useful side, I have found so many other examples to bolster my general argument about other periods. In particular, my research sent me off examining the records of major volcanic eruptions, and the results are, I think, quite powerful.

And now, the first lesson.

Recently, I wrote about the massive catastrophe that swept many societies around the world around 2200BC – or the “4.2ka BP” event. Some have attributed this to a cosmic calamity, like a meteor strike, but I think I now have the answer. It must have been volcanic-related, and in a very unusual way.

Let me explain the rationale for this. The power of eruptions is measured through the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI), which is similar to the better-known Richter scale for earthquakes. Like the Richter scale, the index is logarithmic, so each point on the scale is ten times larger in terms of ejecta than the preceding: a VEI of 6 is ten times larger than a 5, which in turn is ten times more than a 4. A grade 5 produces a cubic kilometer of ejecta; a 6 produces ten cubic kilometers, and a 7 more than a hundred cubic kilometers. By this standard, the eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii in 79 CE was a 5, and the famous Krakatoa blast of 1883 was a 6, a “colossal.” So was Pinatubo in 1991. (Estimates of the exact power of historical volcanoes are open to some debate). Just this past January, the Tonga volcano produced a Grade 6, the largest of the present century.

And then there are the real empire-slayers, the monsters that potentially destroy civilizations. To find 7s (supercolossals), we would look to the very well-studied Tambora blast of 1815, or the less well-known eruption at Samalas, on the Indonesian island of Lombok, in 1257. Such also was the Paektu eruption in northeastern China, which occurred in the mid- or late tenth century (estimated dates vary widely, but 946 is a common estimate). Thankfully, it has been a very long time indeed since the Earth experienced a “megacolossal” grade 8 eruption, with a thousand cubic kilometers of ejecta. One of the last such events, 74,000 years ago, came close to driving humanity to extinction.

Grade 7’s have been very, very rare. Here is a list of all the ones known since 2500BC, and their probable dates:

c.2300BC Cerro Blanco Argentina – 7

2264BC Paektu – 7

2030BC Deception Island – either a 6 or a 7

1610BC Minoan eruption, Santorini – 7

232AD +/-5 Hatepe eruption, Taupo volcano, New Zealand – 7

430AD Lake Ilopango – either a 6 or a 7

535AD Unknown location, a 6 or a 7; and possibly also another one of that magnitude within a few years. Lake Ilopango?

946AD Paektu – 7

1257AD Samalas – 7

1452-1453AD “mystery” blast, location unknown – either a 6 or a 7

1465AD “mystery” blast, location unknown – either a 6 or a 7

1815AD Tambora – 7

If we count the “possibles” which are either 6 or 7, that is only around a dozen in 4,500 years, but they are very far from evenly distributed. Almost certainly we are missing some. I can think of a couple of candidates where we might be looking for others, eg in 626AD, about which I have also written. Do we really see stretches of a half millennium or so without a single 7? For the sake of argument, let’s assume that we are missing half of the ones that actually occurred. That would mean we would expect a Grade 7 every two hundred years or so, maybe longer. But now look again at that table, which suggests not one, but an astonishing TWO Grade 7s within just a generation or so in the 23rd century BC, and at exactly the time that the third millennium crisis was getting under way. We should add to that a couple of other Grade 6’s in the same era, including Mount Veniaminof in Alaska. In 2030 BC, the Deception Island eruption in the South Shetlands was either a 6 or a 7.

Any discussion about the third millennium crisis surely has to begin with that hyper-active volcanic context.

And the second lesson

Look at that event of c.232, the Hatepe eruption. This has long been a real puzzle, as it was traditionally dated to 180AD, and at that date, we don’t see the kind of sweeping and immediate consequences we might expect. But if we relocate it to 232 or so, it makes wonderful sense. For reasons that are not entirely understood, eruptions tend to group in families, and the years around the 230s were one such era. After Hatepe, there was a Grade 6 in Kamchatka around 240 (Ksudach), and one in Alaska (Mount Churchill) around 245 (admittedly, those dates are open to a lot of guesstimating).

More significant, this was the start of the appalling third century crisis that swept the Mediterranean world in particular between 235 and 270, when “There were at least 26 claimants to the title of emperor, mostly prominent Roman army generals, who assumed imperial power over all or part of the Empire. The same number of men became accepted by the Roman Senate as emperor during this period and so became legitimate emperors.” Roman emperors became rather like London buses: don’t worry if you miss one, another one will be along in ten minutes. The economic crisis was catastrophic, currencies and trade collapsed, and as in most such eras, a horrific plague raged in the late 240s: it might have been measles, or smallpox, and it was devastating.

This was the Plague of Cyprian. The then small Christian movement earned enormous credit for the work believers did tending to the sick and maintaining support networks. Pagans conspicuously behaved less bravely and less altruistically. When the plague threat eventually faded, Christian numbers had grown enormously, making the church a potent presence in society and a plausible contender for cultural dominance. When we describe the Cyprianic event today, the name we give it is that of the Christian bishop of the time who described it, and whose writings survived when those of the privileged elites had perished.

But note the date of that crisis: 235, immediately following the now likely date of the Hatepe eruption. As with the third millennium crisis, I don’t think this is any coincidence whatever.

I continue to explore these topics, but trying to defend my mistaken statement about the origins of Revelation actually led me in some really useful directions.

So again, mea culpa.