Evangelical luminary Ron Sider died in August. A key leader—perhaps the key leader—in the evangelical left, he sought to organize a theologically conservative but politically progressive movement that would challenge evangelical support for President Richard Nixon. In last month’s post, I left off with Sider’s unsuccessful campaign to get evangelicals to vote for Democratic challenger George McGovern. But not long after, Nixon became embroiled in the Watergate scandal, and Sider saw a new opening . . .

***

“There is a new movement of major proportions within evangelical circles,” the still-unknown Messiah College professor Ron Sider wrote in early 1973. “It is still a minority movement, but it is widespread and growing. This emerging group of evangelical social activists … needs direction.” Members of the now-defunct EFM proposed a workshop to be held over Thanksgiving weekend. Hashing out plans in April at Steak and Four Restaurant near Calvin College in Grand Rapids, they sought to infuse symbolic value into what they hoped would be the evangelical left’s coming-out party.

First, they decided to meet not in suburban Wheaton, the initial suggestion, but instead at the YMCA in downtown Chicago. Just down the street from the historic Pacific Garden Rescue Mission, the YMCA’s location pointed to evangelicalism’s nineteenth-century legacy of social action and urban concern.

Second, organizers, searching for consensus among a broad range of traditions and interest groups from which a movement could be launched, sought diversity. They invited Black evangelicals and white evangelicals; old and young; evangelists and relief workers; and leaders from a variety of evangelical traditions.

Third, they decided that conference delegates should release a concise, hard-hitting manifesto that would articulate their social concerns to the evangelical world and the national media.

Fifty evangelical leaders, some of the most influential in the younger generation, felt the weight of history when they finally convened on a chilly, foggy Friday morning in late November for the Thanksgiving Workshop of Evangelical Social Concern. After an opening address in which Sider instructed those gathered to “not hesitate to stop and pray” when they got bogged down in debate, delegates immediately declared their opposition to Watergate, the Vietnam War, Nixon, and fellow evangelicals who blindly supported the president.

In a major address Tom Skinner acknowledged that evangelicals had “missed the Civil Rights movement,” stating that it was not too late to “emphasize social sins and institutionalized evils as vigorously as personal sins.” Bill Pannell said that “a new breed of evangelicals” had arrived, that the time for “significant breakthroughs was now.” Sider concurred, “I don’t think it is mere rhetoric to say that we have come together at a moment of historic opportunity.” In a prescient forecast, he predicted that “for better or for worse, [American evangelicals] will exercise the dominant religious influence in the next decade.”

If the Workshop enjoyed consensus in its criticism of conservative politics, it nonetheless encountered difficulties in trying to draw up its manifesto. The composition of what became the Chicago Declaration, a process begun months before the Workshop itself, was plagued by fits and starts. The drafting committee’s first attempt was so strident that Frank Gaebelein, a sympathetic editor at Christianity Today, proclaimed it “heretical.” Civil rights activist John Alexander, no conservative himself, agreed with Gaebelein, calling the initial draft “leftist propaganda.”

Delegates at the Workshop itself continued to criticize the more moderate revised draft. At four pages, everyone agreed, it was too long. A more cutting critique came from Black participants, who perceived hints of “evangelical triumphalism.” How could the evangelical left, they asked, use self-congratulatory language after its own tradition had failed to embrace the civil rights movement? After someone blamed fundamentalist doctrine for their failures—“We’ve been victimized by our own heresy,” a white delegate said. “We’re still good people”—William Bentley, president of the National Black Evangelical Association, retorted, “What does good mean? If you are part of an oppressing community, your goodness means nothing to me.”

Very quickly, Sider recalled, “the lid blew off.” Black participants sharply attacked the planning committee for including only one Black member. Then over a separate lunch of turnip greens and ham hocks prepared “for atmosphere,” they drew up an alternative declaration much more radical than the original. Palpable tension permeated the Workshop through the first evening. When delegates after the day’s final session entered the dark streets in search of a snack, they traveled in two racial groups that, according to one participant, “vented their frustration in angry separation.”

The handful of female delegates also demanded that evangelicals “clean up their own houses.” Nancy Hardesty, an alumna of Wheaton and graduate student at the University of Chicago, and Sharon Gallagher of the Christian World Liberation Front in Berkeley discovered that there was no mention of sexism in the first draft of the Declaration. The women caucused and presented their demand for such a statement. As the Workshop progressed, they grew even more offended. Amidst high-powered evangelical executives and scholars, one woman felt as if “she had walked into an Eastern men’s club. The men tended to be insensitive to women as people.” Delegate Ruth Bentley, for example, was listed as “Mrs. William Bentley.” And when the section in the Declaration on sexism was discussed, Gallagher reported that the few women present were “commanded to speak and then expected to shut up when the men felt the issue had been covered.” Evangelical men, she suggested, regarded women as little more than personal house slaves.

Pacifists added to the ferment. John Howard Yoder, president of Goshen Biblical Seminary, complained, “Blacks have a paragraph they can redo; women have a word they can redo; but there is nothing at all about war. It contains something about the military-industrial complex being bad for the budget, but nothing about it being bad for the Vietnamese.” Yoder, supported by fellow Anabaptists Ron Sider, Jim Wallis, Dale Brown, and Myron Augsburger, persuaded the delegates to insert the following into the Declaration: “We must challenge the misplaced trust of the nation in economic and military might—a proud trust that promotes a national pathology of war and violence which victimizes our neighbors at home and abroad.”

This agreement on what to say about American militarism led the way to resolution over the controversial questions of gender and race. After the initial shock of unexpected disagreement, all sides rallied and rediscovered their common enemies: racism, Nixon, unchecked capitalism, and theological liberalism. After a coffee break late Saturday afternoon, Black delegates decided to “let up,” according to attendee Marlin Van Elderen. Then Stephen Mott, a professor at Gordon-Conwell, interceded on behalf of Nancy Hardesty who wrote the following sentences into the Declaration: “We acknowledge that we have encouraged men to prideful domination and women to irresponsible passivity. So we call both men and women to mutual submission and active discipleship.” Despite dissent from some, delegates accepted the insertion. Participants began approving section after section of the reworked document, and by the final Saturday session, they had nearly completed their task. On this evening, Sider recalled, “one group of black and white brothers and sisters went out to enjoy soul food together.”

The final text of the Chicago Declaration confessed that evangelicals had failed to defend the social and economic rights of the poor, the oppressed, and minorities. It attacked America’s materialism, sexism, and “pathology of war.” It pledged to acknowledge God’s “total claim upon the lives of his people,” even in the long-distrusted political arena. “We endorse no political ideology or party,” signers maintained, “but call our nation’s leaders and people to that righteousness which exalts a nation.” This less radical version, written by Jim Wallis but heavily edited by Paul Henry “not to sound too harsh, anti-American,” eliminated references to Nixon’s “lust for and abuse of power” and alleged United States involvement behind the overthrow of the Allende government in Chile. It instead reflected a new moderate consensus. Final approval was given to the Declaration during a worship service on Sunday morning. When the vote had been tallied, Sider rose to speak of “a deep sense of presence and guidance of the risen Lord.” He then invited delegates to sing the Doxology, marking the end of a remarkable weekend of progressive politics and evangelical piety.

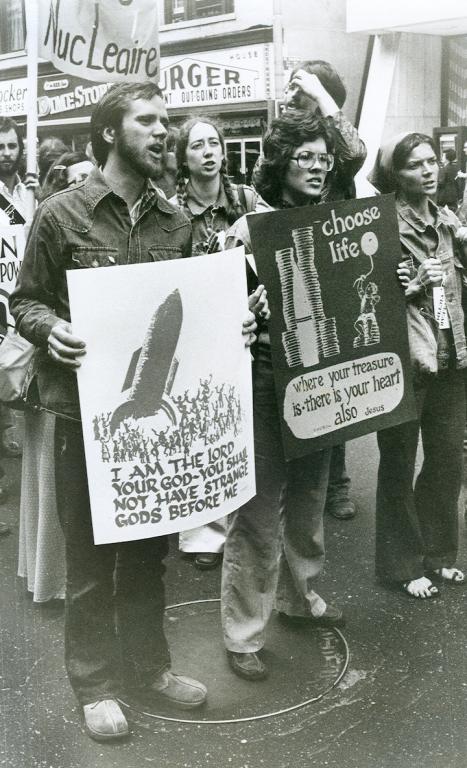

The media, fascinated by the idiosyncratic blend of conservative theology and progressive social critiques, reported widely on the weekend. Reporters from United Press International, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, and others framed their reports in terms of mainline Protestant stagnance and evangelical resurgence. A reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times suggested that “some day American church historians may write that the most significant church-related event of 1973 took place last week at the YMCA Hotel on S. Wabash.” Upon hearing of Evangelicals for McGovern and the Chicago Declaration, William Sloane Coffin, a prominent civil rights and peace activist who served as a mainline chaplain at Yale, declared, “Now this is the real McCoy, rooted in deep personal experience! … I’ve always suspected that the future was with these Evangelical guys.”

In my next post, I’ll chronicle the Declaration’s afterlife. It turned out that the future was not in fact with “these Evangelical guys.”