On a recent trip to New York City to binge on musical theater, my companion and I fit in the Broadway and West End hit Six. It was excellent fun. As someone who teaches on the Tudors each year, I found myself wanting to explain the historical jokes to my friend and trying to decide whether the musical was an asset to those of us who do early modern history as we try to convince the world of our relevance. When I returned to my classroom with a t-shirt from the musical listing all the wives, my students’ response to my trendiness was gratifying.

Perhaps Six won’t do for sixteenth century historians what Hamilton did for interest in early U.S. history, but it did raise some questions for me. Are sexy, anachronistically feminist queens what we want to pull students into the classroom or to get them interested in history? Or is it a come-for-Greensleeves-Boleyn-stay-for-the-Puritans sort of situation? Are we baiting and switching or is a re-interest in royalty and high politics just going to be the next trend in historiography?

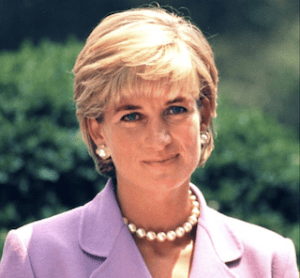

With Queen Elizabeth II’s death, journalists, historians and pop culture analysts all rushed to assess why people in the United States care so much about British royalty. As a child of the 80s and 90s, I was deeply aware of Princess Diana Spencer, but not the rest of the royal family. My wedding happened to be on the day she died, so it is possible I started looking out a bit more for her boys and the outcome of her ex-husband’s romantic pursuits as a result of feeling tied to that family by the coincidence of that date. Still, as a scholar of British history, I’ve never known enough about the royals to answer my friends’ questions or to care that much about whether the British continue to have monarchy or not.

But I did very much enjoy the BBC show Downton Abbey. And the Crown. And Victoria. And I finally watched Bridgerton. These shows are unabashedly consumed with the hierarchy of aristocracy and unearned wealth. They cause their viewers to focus on those whose lives are bound up with inherited power and land. And I’m not alone in my interest. How did a people whose nation was begun with a repudiation of inherited power and a focus on earning wealth through labor manage to become so enamored with not just any aristocracy—but that of the empire that they liberated themselves from? We don’t celebrate the Spanish monarchy, or the Danish, so clearly this is about more than an enjoyment of crowns and palaces. Perhaps, we like aristocrats, whose wealth is greater than that allotted to the residual Western European monarchies.

Heather Cox Richardson and Joanne Freeman have analyzed this in their podcast Here and Now. They focus on the 3 long-lived monarchs, whose reigns overlapped with the existence of the United States: George III, Victoria, and Elizabeth II. George III was the focus of a long list of crimes in the Declaration of Independence (the parts that we don’t usually read on Independence Day). Queen Victoria represented a sort of womanhood that was idealized by women in the nineteenth-century United States. And her mourning her husband in the aftermath of his death mapped onto the large-scale mourning that occurred in our nation after the Civil War. Elizabeth II allowed us to respect the dismantling of empire at the same time that we were expanding our own during the Cold War.

Of course, the culture of celebrity is much more widespread than our focus on British royalty. Katelyn Beaty’s Celebrities for Jesus outlines some of the ways our wider society’s obsessions with VIPs and proximity to wealth and power has infiltrated the church. Focusing on people and organizing around them rather than the longer-term, ordinary structures of the church, consistently risks the church’s mission. We are at the mercy of the morality and talent of a few names. It feels like a far cry from the multi-faceted Body of Christ, with its focus on the spiritual gifts of all of us—the priesthood of all believers.

As I teach early modern British history, I know how much my students enjoy a good story of a royal marriage or aristocratic conflict. However, as a point of focus, they are the opposite of what my biblical upbringing encouraged me to orient myself toward: the least of these. I try to include some of Christopher Hill’s World Turned Upside Down alongside Linda Porter’s The First Queen of England. While we may have human tendencies to orient toward power, scholars and teachers have the opportunity to work against the grain, and to encourage a focus on the lives of people who are no less heroic for having made their history far from the command centers or luxurious manors. They also are the beloved children of God and their history matters.