My past caught up with me last week.

I stood on the West Campus of Duke University for the first time in more than nineteen years. A school group was visiting, their tour buses parked in the road circling past the gothic tower of the university chapel. I didn’t want to become part of the background for dozens of selfie pictures, so rather than join the crowd on the lawn, I sat on a bench–eating my breakfast bagel from the nearby Beyu Blue coffee shop.

The cold stone of my seat didn’t mar the almost surreal beauty of the moment for me.

Nineteen years-ago I had been an anxious graduate student on the cusp of defending my dissertation. I wasn’t sure if I would pass the defense. I wasn’t sure what the future would hold; I wasn’t sure if my dissertation would be published, much less if I would find a tenure-track position in academia. Despite the years of coursework, language study, archival trips, and hundreds (hundreds) of books and articles read, analyzed, and discussed, I still felt like a novice.

I wouldn’t have guessed that nineteen years later I would sit in the same spot my husband used to pick me up after evening seminars (we only had one car)—but this time, instead of a graduate student, I would be a full professor at a research university. I remember one night my husband surprised me with flowers for our 6-month wedding anniversary. I can still see him holding the bouquet as I walked out from the divinity school to our car, right under the shadow of the chapel. I am certain that neither of us would have guessed that the research I was doing on medieval sermons, that I was to defend a few miles down the road at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in December 2003, would become the foundation for a bestselling book.

But it did.

North Carolina was where my academic career began. As I sat in front of Duke chapel last week, drinking my coffee, I thought about my dissertation research. I reread it not too long ago, shortly after receiving a newly-released paperback of my dissertation book—The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England. While it was written for an academic audience, I could still see the beginnings of my thought process that would eventually lead me to The Making of Biblical Womanhood. So, I thought today I would let you glimpse that young scholar who rode the bus between UNC-CH and Duke and wrote a dissertation on fifteenth-century sermons. If nothing else, the excerpt below from The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England is proof that good ideas are often long in the making.

North Carolina was where my academic career began. As I sat in front of Duke chapel last week, drinking my coffee, I thought about my dissertation research. I reread it not too long ago, shortly after receiving a newly-released paperback of my dissertation book—The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England. While it was written for an academic audience, I could still see the beginnings of my thought process that would eventually lead me to The Making of Biblical Womanhood. So, I thought today I would let you glimpse that young scholar who rode the bus between UNC-CH and Duke and wrote a dissertation on fifteenth-century sermons. If nothing else, the excerpt below from The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England is proof that good ideas are often long in the making.

I hope you enjoy!

Excerpt from pp. 36-39, Chapter 2 “Pastoral Language: ‘Christ’s People, Both Men and Women,” from Beth Allison Barr, The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England (The Boydell Press, 2008 and 2022).

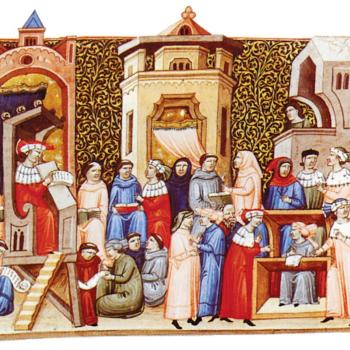

John Mirk concluded his Festial sermon on the Lord’s Prayer with an exemplum about a singlewoman who had lived as a mistress for many years. One day when she was in church, she listened to a sermon about the “horrible pains of hell ordained” for those who lived in lechery and “would not leave it.” The words of this sermon so convicted her that “she was contrite and stirred by the Holy Ghost, that she went, and shrove her, and took her penance, and was in full purpose forto have left her sin for always after.” Yet on her way home she met her lover who seduced her with calming words. “If all things were such that is preached, there should no man nor woman be saved; and therefore leave it not, for is [i]not such. But be we hereafter of one assent, as we have been before, and I will plight you my troth that I will never leave but hold you always.” Then “turned the woman her heart and did the sin as they did before.” Shortly thereafter they both suddenly died. A concerned priest prayed that God would show him the state of their souls, and as he walked past a body of water one day, he saw a dark mist hovering above the surface and heard the voices of this man and woman emanating from the darkness. “Then said the woman to the man, ‘Cursed be you of all men, and cursed be the time that you were born, for by you I am damned into everlasting pains.’ Then answered the man: ‘Cursed be you and the time that you was born, for you have made me damned forever! For had I once been contrite for my sins as you were, I would never have turned as you did; and if you had held good covenant with him that made you, you might have saved us both. But I promised that I would never leave you. Wherefore go we now both into the pain of hell that is ordained for us both!’” The sermon then abruptly concludes, “From the which pain God keep you and me, if it be his will. Amen.”[ii]

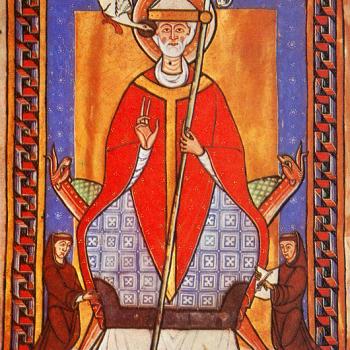

This story illuminates several provocative points about men and women in the late medieval parish, including at least two about male and female spirituality. First, the story portrays the fictional female parishioner as an ordinary member of sermon audiences who listened and attempted to implement the spiritual lessons she learned. Second, the story portrays the fictional male character as not in church with his mistress, and—as implied by his shout, “you might have saved us both”—perhaps even dependent on his mistress for (some) spiritual assistance. In short, this story suggests that women played critical roles in the pastoral world of late medieval England: listening to sermons (perhaps more than their male counterparts), attempting to implement the spiritual lessons they learned, and—for better or for worse—influencing the spirituality of men around them.

From this perspective, it is not surprising that the sermon in which the story is embedded uses language targeting female, as well as male, parishioners. For example, it opens with the salutation: “Good men and women, you shall know well that each curate is held by all the law in holy church, to expound the ‘Pater Noster’ to his parishioners once or twice in the year; and if he do not so, he shall be hard accused of God for his negligence.” The sermon text then explains: that the “’Pater Noster’ be vii prayers the which each man and woman have great need to pray God for; for that puts away the vii deadly sins, and gets grace of God…both to the life and to the soul”; that parishioners who acknowledged God as their father, as the Pater Noster demanded, were “brother and sister in God”; and that parishioners should employ the Pater Noster to defend themselves against the “enticing fiends” who slyly “bring a man or a womaninto sin.” Through the use of explicit gender-inclusive language, this sermon makes its point clear: to convince all parishioners—both men and women—of their need for understanding and using spiritual teachings in their everyday lives.[iii]

Nor is the explicitly gendered language of this sermon anomalous. The compiler of Lincoln Cathedral MS 133 echoed the pattern found in the Lord’s Prayer sermon, generously incorporating both implicit gender-inclusive language (gender neutral nouns, such as people and friends, and pronouns, such as they) and explicit gender inclusive language (specifically stating men and women) within the ten sermons he copied from Festial—sometimes even going beyond the gender sensitivity of other Festial manuscripts. The Septuagesima sermon from Bodleian Library MS Gough Ecclesiastical Topography 4, for example, records:

Thus, good men, know that Adam and Eve were both holy…[iv]

Lincoln Cathedral MS 133 records instead:

Thus good man and woman may know that Adam and Eve were both good and holy…[v]

…In sum, Lincoln Cathedral MS 133 reveals the choices a clerical scribe made about language within his text—what words to include, what words to exclude, and what phrases to alter. These choices were certainly influenced by the base text used, but they were also influenced by the copyist himself. Helen Spencer has noted that, “Because a compiler selects and rearranges his materials, he is making something new out of what was old….A compiler may reveal much about himself by his selection of extracts, even though he expresses himself through the words of others…”[vi] As this chapter demonstrates, the choices made in sermon manuscripts such as Middle English Sermons and John Mirk’s Festialreveal clerics intentionally providing room for women within the language of their texts. Like Mirk’s sermon on the Lord’s Prayer and Lincoln Cathedral MS 133, clerical attentiveness to women within sermon language occurred often and in ways suggesting both individual attentiveness on the part of clerics as well as a general pattern of attentiveness at moments of pastoral care. Thus, when Margery Kempe declared that she “would give every day a noble to have every day a sermon”, perhaps some of her attraction to hearing sermons stemmed from the female-friendliness of pastoral language.[vii]

Words matter, y’all. They always have.

Happy Thanksgiving!

[ii]John Mirk, Mirk’s Festial: A Collection of Homilies, by Johannes Mirkus ed. Theodore Erbe, EETS (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, and Co., 1905), 287-288.

[iii]Ibid., 282, 285-286.

[iv]Ibid., 68.

[v]Lincoln Cathedral MS 133, f. 106r.

[vi]H. Leith Spencer, English Preaching in the Late Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993), 270.

[vii]Margery Kempe, The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Sanford Brown Meech with prefatory note by Hope Emily Allen and notes and appendices by Sanford Brown Meech and Hope Emily Allen, EETS os 212 (London: Oxford University Press, 1940), 142.