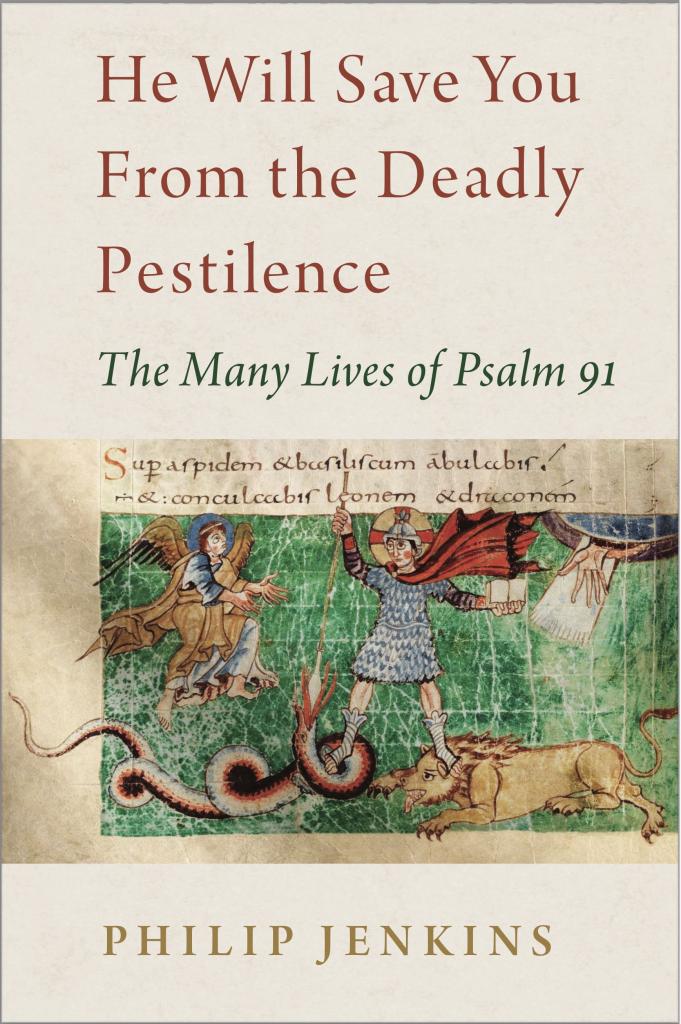

My new book is He Will Save You from the Deadly Pestilence: The Many Lives of Psalm 91 (Oxford University Press). That particular psalm has been used widely throughout Western history, as a political manifesto and a means of understanding plague and pestilence, and also as a definitive protection against demons. Here, I want to talk about its use in the nightly prayer service of Compline. Such a prayer in the darkness seems a highly appropriate thing to discuss at this time of year, immediately following the shortest day – the year’s midnight. (See Lisa Diller’s recent post at this site).

Compline is a lovely event, widely used in the Episcopal church as well as the Catholic tradition. But historically, it was very much a monastic phenomenon, which made it very relevant to the monks, nuns, and friars who for so long would have constituted the literate elites of Christian societies. In the West, virtually all those monastics ended every single day of their clerical lives with the service of Compline, in which 91 was a fixture. How could those frequent reciters and listeners help carrying its words into those other contexts – of writing the histories, and telling the stories by which we know the Middle Ages?

I include the psalm’s most-used protective verses at the bottom of the present post.

Psalm 91 is worth reading in detail, but what makes it so important is that it is not a prayer for protection, it is an outright statement the believer will be guarded against all sorts of harm. No ifs or buts. This is what God shall do. This was all invaluable in a world that deeply and thoroughly believed in the power of demons, which were especially active during the hours of darkness, and the time of sleep.

Pioneering monks and desert hermits refer to the psalm so much that I have described this text as a charter of monasticism. One distinguished pioneer of distinctively Western monasticism was Cassiodorus, who in the sixth century produced his popular Exposition of the Psalms. This is lavish in its praise of 91:

This psalm has marvelous power, and routs impure spirits. The Devil retires vanquished from us through the very means by which he sought to tempt us, for that wicked spirit is mindful of his own presumption and of God’s victory. Christ by His own power overcame the Devil in His own regard, and likewise conquers him in ours. So this psalm should be recited by us when night sets in after all the actions of the day; the Devil must realize that we belong to Him to whom he remembers that he himself yielded.

Christians in this era advocated using any and all psalms in prayer, and some offered suitable rotations to work through the full Psalter over a short period, but 91 was rare in being deployed each and every day.

That regular usage contributed to creating the evening prayer service of Compline. The Christian compline tradition was probably begun by Basil the Great, but Benedict introduced it to the West, giving it its later Latin name, completorium, marking the completion or end of the day. (The German word is still Komplet). The Western Compline used 91 alongside two other psalms, 4 and 134, and that general threefold structure persists today. Today, the service may provide a psychological blessing, a shedding of daily cares before moving to a new stage of relaxation, but in its origins it was intended to fortify the believer against the spiritual perils of the night.

It is hard to overstate just how pervasive that liturgical usage was. One famous later monk (I’ll tell you his name shortly) warned of the dangers that could arise during contemplation, when so many devils “stand to profit if they can destroy and exhaust us with false lights and raptures of their own devising.” But believers could stand secure. Using his translation of the distinctive Latin version of the psalm, which differs from the King James text I quote below, that monk then quotes the psalm that is

chanted every night in the monastic Complin [sic] when the shadows fall upon the cloister and the monks are ending their day of prayer. ’I will be with him in trouble. I will rescue him and honor him. The angels are at our side, holding us up less we should dash our foot against a stone. We could not travel through the forest that the spiritual life has now become unless His power carried us onward, where we tread upon the asp and the basilisk and never feel their sting, and never suffer harm! Altissimum posuisti refugium tuum. We have made the Most High God our refuge. The scourge will never touch us.

The monk was Thomas Merton, writing in 1953, when Dwight Eisenhower was president of the United States, when IBM was marketing the first mass-produced computer, and when Marilyn Monroe was in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Some ideas last a very long time.

Should you wish to do the Compline service yourself, and there are many worse ways of ending a day, you can find the short and easy text here. It is ideal as the days draw in, and the darkness gathers.

You can also watch this beautiful choral Compline service – which happens to come from my old Cambridge college, of Clare.

PSALM 91: 3-13

Surely he shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler, and from the noisome pestilence.

He shall cover thee with his feathers, and under his wings shalt thou trust: his truth shall be thy shield and buckler.

Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day;

Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday.

A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee.

Only with thine eyes shalt thou behold and see the reward of the wicked.

Because thou hast made the Lord, which is my refuge, even the most High, thy habitation;

There shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling.

For he shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways.

They shall bear thee up in their hands, lest thou dash thy foot against a stone.

Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.