On January 8, thousands of Bolsonaro supporters stormed the Brazilian Congress, Supreme Court, Senate, and Presidential palace. Many people reported on the event—and a forthcoming piece I co-wrote on the history of evangelical connection to right-wing politics in Brazil will hopefully come out soon—but I would like to highlight some evangelical pastors who supported Bolsonaro and have not condemned the criminal acts against the Brazilian democracy. The Brazilian insurrection underscores that Christian nationalism (and/or “the religious right”) is a transnational phenomenon—as Ben Cowan demonstrated in his Moral Majority Across the Americas. It also pokes additional holes in the notion that there is a wide gap between U.S. evangelicals and Latin American “evangélicos” regarding their theopolitical dispositions when it comes to the majority expressions of the movement. In my own work, I tried to trace a significant stream of the historical roots of Brazilian conservative evangelicalism—and its connections to U.S. evangelicalism. These connections were fully displayed in the evangelical presence in the Brazilian insurrection.

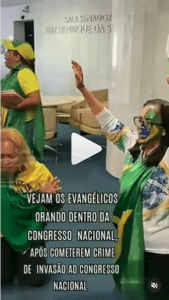

The bibles being proudly shown and Christian worship songs being sung during the insurrection were indicative of the involvement of evangelicals in the event. Evangelical leaders led caravans and organized people who went to Brasília, Brazil’s capital, to eventually invade and vandalize government buildings. One evangelical pastor led a group that announced: “Fight now and be a part of history.” During the insurrection, some evangelical politicians shared posts that offered a favorable impression of the invasion, which they later deleted. It has been reported, for example, that evangelical pastor and politician Júnior Tércio and his wife, Clarissa, were accused of crimes against democracy for encouraging criminal acts. Another evangelical pastor, Elias de Souza, reportedly lead a caravan to the capital. Other less-known evangelical leaders and parishioners were among those destroying government buildings.

Most nationally known evangelicals were not directly involved in the Brazilian insurrection. However, some in the progressive evangelical minority have noted that these leaders strengthened and legitimized right-wing radicalism for years. They also did not explicitly condemn the acts in their first responses to what had happened. For example, Silas Malafaia, the famous Assemblies of God pastor who is a strong Bolsonaro supporter, said that he was against excesses but, hinting towards legitimizing the events, concluded that “the people’s patience has limits.” The pastor of former first lady Michelle Bolsonaro’s Baptist church posted a video of the criminals inside government buildings without comments condemning the crimes. Baptist pastor and former senator Magno Malta said that the invaders could not be compared to criminals and terrorists. The list goes on…

The right-wing dispositions in Brazilian evangelicalism are not odd exceptions. Recent polls suggest that two-thirds of Brazilian evangelicals support military intervention and do not believe that Lula, the democratically elected Brazilian president, was the legitimate winner. According to a poll by Atlas/Intel, although most of the Brazilian population believes Lula was the legitimately elected president, only 28% of evangelicals believe he won the elections. Similarly, over 64% of Brazilian evangelicals support military intervention, while most of the population does not. Evangelicals are three times more likely to support a military dictatorship than the general population. Although the majority does not support the January 8 insurrection, they are twice more likely to have supported it.

When it comes to Brazil, I do not mean to define “evangelical” solely by the political affiliations of the majority of self-described evangelicals. Still, neither do I want to kill the term with a thousand qualifications. In my home country, “evangélico” is primarily synonymous with “Protestant.” I also believe in people’s self-description when they call themselves “evangélico.” According to several studies, most are conservative theologically, socially, and politically. The right-wing political affiliations of evangelical leadership are thoroughly documented in Portuguese, some in English too. The less prominent evangelical left has received less attention. And as important as showing the diversity in the movement is, naming the majority dispositions and general trends is more crucial than ever.

In Brazil, journalists and social scientists have done a better job than historians tracing the major trends and connections of evangelical political involvement. For example, Ricardo Alexandre’s E a Verdade Vos Libertará, Juliano Spyer’s Povo de Deus, Andrea Dip’s Em Nome de Quem?, and Mariana Lacerda’s O Novo Conservadorismo Brasileiro have, in different ways, warned of the dangers of the growing right-wing evangelical presence in Brazilian political life. Evangelical historians in Brazil—not unlike many in the U.S.—have mainly invested their time in showing the diversity within the movement, sometimes giving the impression that such diversity had more statistical and strategic relevance than it does. But there are indicators that the progressive minority is also occupying more spaces.

In the last decades, Brazilian progressives—including Lula’s Workers’ Party—have noticed the importance of courting evangelicals; they have intentionally nurtured relationships with progressive evangelical coalitions. Brazilian evangelicals have also shown to be quite pragmatic regarding political power—not always shy about strategically shifting their allegiances. Progressive evangelicals have also been organizing, and the few progressive evangelicals serving as elected officials have continued to emphasize that there are social justice-focused, inclusive ways to be evangélico. However, the many layers sustaining evangélico politics include religiously-legitimized beliefs that limit possibilities in the contemporary context. The discourses against gender minorities, adoption of dominium ideologies, resistance against politics of inclusion, and “us” versus “them” mentalities of right-wing Brazilian evangélicos are not just political preferences; they are theologically-grounded convictions. Evangélicos are also growing in numbers and influence as Brazil moves closer to becoming a majority-evangélico nation. In light of this growth and conservative evangélico success, the U.S.-Brazil religious networks that have advanced transnational conservatisms are poised to strengthen. Transnational progressive resistance must also increase to counter this trajectory successfully.