Fisk University is a private, historically black university, founded in 1866 and located in Nashville, Tennessee. It opened its doors in the same year that a terrorizing race riot broke out in neighboring Memphis, Tennessee. The university is named for General Clinton B. Fisk, who had at one time been in charge of the Freedman’s Bureau in Nashville. The school grew rapidly in its early years, focusing on training educators for African-American schools throughout the South. Among Fisk University’s first graduates included Virginia E. Walker Broughton (1856–1934), who taught in Memphis public schools until she followed a call from God to join the Bible Bands Institute in 1887 and teach women the bible.

Within five years of training a student body of 500, it became apparent that Fisk University needed to allocate a large plot of land and construct permanent buildings for its continued growth. The university’s treasurer and choir leader, George L. White, organized a group of students in 1871 to travel and perform concerts, as a means to collect funds for the building campaign. This a capella troupe, called the Fisk Jubilee Singers, travelled the country and popularized the genre of spirituals. In its first year of travel, the Fisk Jubilee Singers raised $20,000 towards their building campaign and brought awareness to the existence of Fisk University, leading to matriculation from many African-American students.

Gustavus D. Pike’s history, The Jubilee Singers (1874) describes the evolving style of the Fisk Jubilee Singers:

Mr. White commenced to teach Sunday school songs, but went on to drill his choir to sing operatic music. He started North in ’71 to sing the more difficult and popular music of the day, composed by our best native and foreign artists; but he found his well-disciplined choir singing the old religious slave songs, his audiences demanding these, and satisfied with little besides, till the cries of the oppressed went echoing all over the North, as some rare heaven-born relic of a bondage past, the history of which had been near the heart of God for the past two hundred years. The Jubilee Singers made known to us how the poor slave besought the God of heaven in song, until he gave victory. (Pike, The Jubilee Singers, 47–48)

When the Jubilee Singers performed, members of the group shared their stories of slavery and freedom. Thomas Rutling recounted how his mother was whipped frequently and taken away from him when he was two. He had numerous siblings, some of which were sold and separated from one another. The climactic part of Rutling’s account was his story of freedom. He recalled:

One night, the report of Lincoln’s Proclamation came. Now, master had a son who was a young doctor. I always thought him the best man going: he used to give me money, and didn’t believe much in slavery. Next morning I was sitting over in the slave quarters, waiting for breakfast, when the young doctor came along and spoke to my brother and sister, at the front door. I supposed it was about work; but they jumped up and down, and shouted, and sang, and then told me I was free. (Pike, The Jubilee Singers, 56)

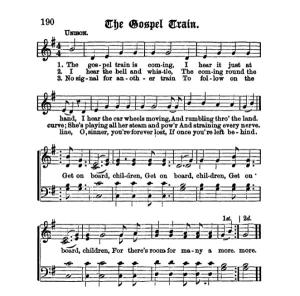

“The Gospel Train (Get on Board)” (1873) is a signature example of an African-American spiritual that the Fisk Jubilee Singers performed. This spiritual was born from an era that unified the geography of a nation through the bond of novel steam technology wedded to the power of tempered steel. The plan for the transcontinental network of railway transportation began in 1862 and the union between the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railway took place at Promontory Point, Utah on May 10, 1869. Harnessing the language of trains in spirituals and hymns had picked up steam throughout the 1860s. Here are the lyrics to this widely recognized arrangement of the Fisk Jubilee Singers:

V1

The gospel train is coming,

I hear it just at hand

I hear the car wheels moving,

And rumbling thro’ the land

C

Get on board, children (3x)

For there’s room for many a more

V2

I hear the bell and whistle,

The coming round the curve

She’s playing all her steam and pow’r

And straining every nerve

V3

No signal for another train

To follow on the line,

O, sinner, you’re forever lost,

If once you’re left behind

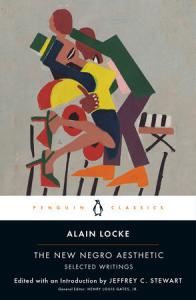

Alain Locke (1885–1954), the father of the Harlem Renaissance, reflected back on the significance of the African-American spiritual for American culture in an essay on music. His comments are worth quoting in full:

The spirituals are [the] taproot of our folk music—stemming generations down from the core of the group experience, in the body and soul suffering slavery and expressing for the race, the nation, for the world, the spiritual fruitage of that hard experience. But they are not merely slave songs or even Negro folk songs. The very elements that make them spiritually expressive of the Negro make them at the same time deeply representative of the soil that produced them. They constitute a great, and now increasingly appreciated, body of regional American folk song and music. As unique spiritual products of American life they’ve become nationally, as well as racially, characteristic. They also promise to be one of the profitable wellsprings of the native idiom in serious American music. In that sense they belong to a common heritage and, properly appreciated and used, can be, should be, will be part of the cultural tie that binds. (Alain Locke, “Spirituals” in The New Negro Aesthetic edited by Jeffrey C. Stewart [New York: Penguin, 2022] 178).

From the genre of spirituals came the genre of gospel music, which Mahalia Jackson (1911–72), the Queen of Gospel, popularized. Spirituals, jazz, and gospel music—while uniquely African-American contributions to the arts—account for a large proportion of uniquely American style of music. In the period nestled between the emergence of spirituals and the rise of gospel music, and contemporaneous with the circuit travels of the Jubilee Singers, John Weldon Johnson wrote a poem entitled “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (1900), which his brother John Rosamond Johnson put to music.

Many Americans heard this hymn, known as the Black National Anthem, performed by Sheryl Lee Ralph, prior to the kick-off of the Super Bowl this past Sunday night. While many people have celebrated the inclusion of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” in the liturgy of the Super Bowl pre-game, others have critiqued the notion of a nation having two anthems.

Sadly, these people are unaware that spirituals, jazz, gospel, and “Lift Every Voice and Sing” emerged in a protracted period where African-Americans had to validate their existence as Americans. They were, in this era, still giving voice to the oppression and suffering they had endured and still endure. It’s during this period that the Great Migration, African-Americans migrating from the South to the Midwest and Northeast, alleviated these people from the racist resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and its accompanying violence in the South.

Unfortunately, when the Great Migration inaugurated a massive shift in population of African-Americans to the North, it brought an unexpected, concomitant surge of prejudice and discrimination from Yankees as well. A wave of White Supremacist, Nativist, and Americanist rhetoric surged through the nation. Individuals like Madison Grant (1865–1937) marshaled zoology, anthropology, and eugenics to justify the Nordic race as the superior race (Cf. The Passing of the Great Race: Or the Racial Basis of European History [1916]). Grant—a founding member of the American Eugenics Society, Vice President of the Immigration Restriction League, and the Secretary of the New York Zoological Society—lobbied and organized caging a Congolese man, Ota Benge, alongside chimpanzees in an exhibit at the Bronx Zoo in 1906, a clear indication of what he felt about the recent rise of African-American residence of Harlem. Interestingly, surrounding neighbors in Manhattan had been caging in Harlem residence by erecting 10 foot wrought iron fencing to separate the Harlem community from adjacent white communities.

So while whites may have preserved the nation’s union and united it with steam and steal technology, the black segment of the nation’s population had to validate and fight for their flourishing. They did so in the face of violent surges of race riots orchestrated by the Ku Klux Klan in the South. When they fled for refuge to the North, they faced a new threat of Yankee, Old-Stock eugenicists, who caged them into a North Manhattan borough.

If you’re wondering why our nation has two national anthems, it’s because one anthem serves a people, who have continually sought full inclusion as first-class citizens in our society, and, at every turn, they have been haunted by the specter of slavery. Yet, their music demonstrates the fullness and beauty of their humanity and bespeaks their restless hope for liberty, with groanings, at times, too deep for words.