I just published the book He Will Save You from the Deadly Pestilence: The Many Lives of Psalm 91. Many things make that psalm highly distinctive among Biblical passages, not least the fact that it alone, among scriptural texts, is quoted by Satan himself. But Satan makes an odd mistake, or a fumble, one that has baffled curious commentators through the centuries. I happen to have the solution, and it is one that actually identifies a long arc in the Jesus narrative – one that we usually miss. The topic is uniquely and centrally relevant to the Lenten season, which began yesterday.

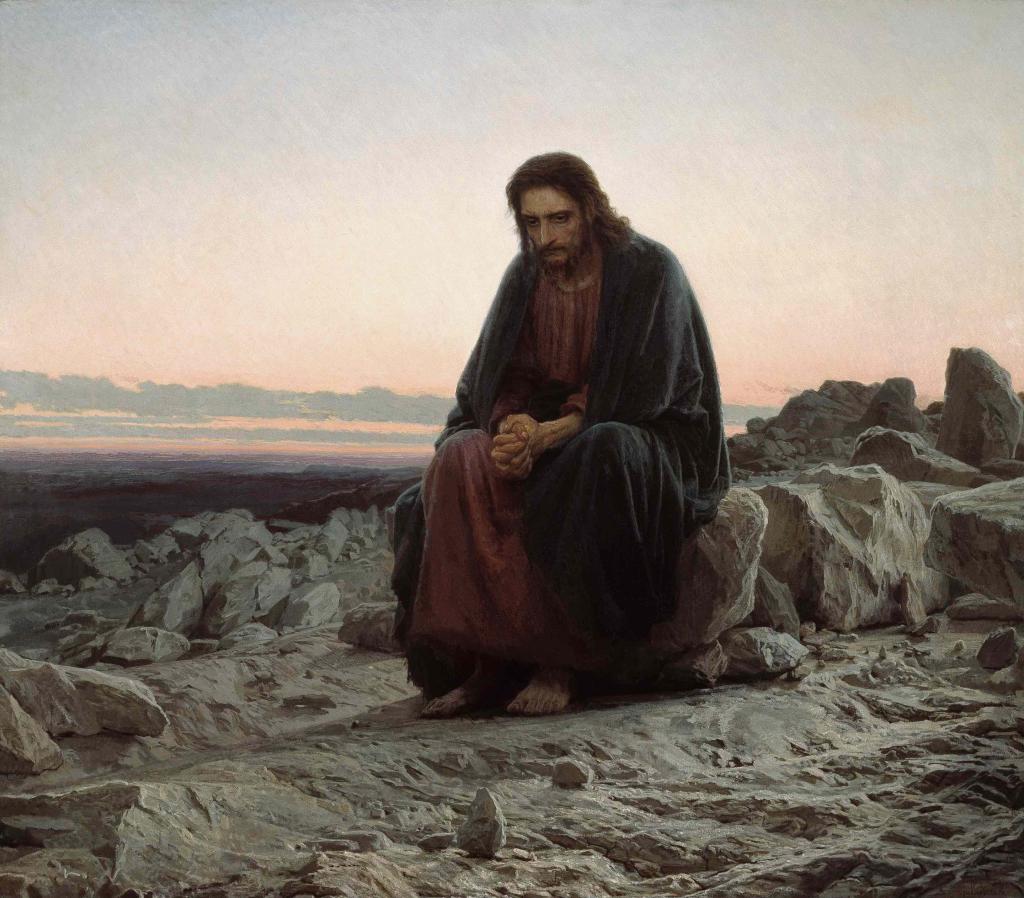

Through the centuries, many artists have depicted the harrowing episode of Christ’s temptations in the wilderness, which is the source of that Lenten idea. Some depict Jesus in dialogue with the tempting Devil himself, while others focus on a solitary Jesus, who presumably is battling these temptations as inner impulses and psychological conflicts. Hearing these seductive calls to action, Jesus must decide whether to reveal his supernatural status by some flamboyant miracle, by casting himself off the Temple. At that point, he hears the assurance of Psalm 91 that the angels will bear him up. But he resists, faithful to God.

Two of the four gospels, Matthew and Luke, recall the strange scene in which the Devil himself quotes Psalm 91, which was odd enough because in its day, this was the exorcism Psalm par excellence. Hearing the Devil quote it is like seeing a cinematic vampire waving a crucifix. Viewed by itself, it might seem like an isolated or even quirky reference. We easily miss the sequel that occurs later in the New Testament itself, most explicitly in Luke, and which completes the wilderness story. When we place the temptation scene in its larger context within the New Testament, both the episode and the psalm become central to the early Christian narrative. In Luke’s gospel, indeed, Psalm 91 becomes the charter of the Jesus movement and of the church. As an indispensable mainstay of early Christian belief, the psalm shaped both the writing of the gospels and their later interpretation.

Three Rejections

Matthew and Luke differ both in detail and in their general concept. In Matthew, the psalm is used in the second of three temptations, and his Devil offers a slightly compressed version of 91. In Luke, 91 is the basis for the third and culminating temptation, and that reflects its critical position in his narrative. Luke integrates the Psalm 91 material into a complex sequence although the denouement does not follow on immediately. In musical terms, it is as if a leitmotif is here introduced, and listeners have to await its reappearance – and in fairness, we have to wait a while. To understand this, we need to analyze Luke’s account of the wilderness encounter in some detail.

The Devil tempts Jesus three times. So you are hungry? he asks. Then turn these stones to bread.

He takes Jesus to a high mountain. Look at all the world’s kingdoms, he says. Just worship me, and I will give you all of them.

Then the Devil takes Jesus to a high point on the great Temple itself and urges him to throw himself off. Does not Psalm 91 say that angels will protect him, so that he will not so much as dash his foot? What better way for a messiah, a Christ, to prove his status to the world, and to show that he is guarded by angels?

Luke and Matthew agree that on each occasion Jesus refuses the temptation, and three times he quotes a verse from Deuteronomy. More specifically, he draws on a section of that book that in modern Bibles appears as chapters 6–8, immediately following the giving of the Ten Commandments. To the first suggestion (in Luke’s sequence), he responds that man shall not live by bread alone. Nor will he worship Satan, responding, “Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God, and him only shalt thou serve.” To the third suggestion, about throwing himself off the Temple, he replies, “Do not put the Lord your God to the test.”

The Missing Verse

From early times, commentators expressed puzzlement that the citation of 91 in the wilderness scene was oddly incomplete. As reported, the Devil quoted what we would call the psalm’s vv. 11–12,

For he shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways.

They shall bear thee up in their hands, lest thou dash thy foot against a stone.

This is a famous passage. But do note that Satan stops there, and does not proceed to the far more celebrated verse 13, as most readers of the psalm would do in that era and later:

Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.

Some quotes are so famous that we complete them automatically. If you hear “Our Father,” it is hard not to think immediately of “which art in Heaven.” Psalm 91 was very famous and well-used, and quoting verse 12 naturally sent you into verse 13. But at this point, the Devil stops. In a sense, he has already said far too much, because any reader of the Psalm knew what came next, and what horribly bad news that was for Satan and his cause. Of course he stops there, because this next verse proclaims the fall of evil forces (like himself), and moreover it contained what were at the time read as evocative messianic references to trampling and serpents.

Naturally, thought some commentators, the Devil would not want to undermine his argument by citing such an embarrassing line. Origen noted this failure to follow through. Incidentally, he also thought that Satan had committed an “exegetical blunder” in suggesting that the Son of God would actually need the help of angels to accomplish anything.

So where did verse 13 go? Why did Jesus not hit Satan back with it? It makes the whole story annoyingly incomplete, and even mysteriously so. In fact, however, if we read Luke’s gospel as a whole, that very v. 13 shortly reappears, centrally and memorably, as Jesus openly proclaimed his messianic mission. Jesus caps Satan’s quotation.

When we read the story of the temptations and the wilderness, we normally read an ending at Luke 4.13: “And when the Devil had ended all the temptation, he departed from him for a season.” But that is not the end of the story. Satan and Jesus would meet again, and sooner in the story than we might expect.

Three Triumphs

In two of his chapters, 9 and 10, Luke presents a series of critical episodes that upend and reverse the Devil’s challenges in the wilderness, and Psalm 91 is pivotal to this story, specifically the allegedly missing v. 13. Among the four gospels, this story appears in fully developed form only in Luke. This may mean that he constructed those connections himself or, more likely, that he alone preserved an ancient narrative of the movement’s beginnings.

Like all good stories in the ancient world, it has a threefold structure.

Luke’s wilderness account features three temptations, which we might summarize as the miraculous feeding; the ascent and the call to worship; and the invocation of Psalm 91. These three reappear, in that very same sequence, in Luke’s later two chapters.

It starts with food and feeding.

We first encounter the famous scene in which Jesus miraculously feeds the five thousand. When invited by the Devil to turn stones into bread, he had quoted the Deuteronomy passage concerning manna, the miraculous bread from heaven, and had refused to be provoked into performing a miracle. Yet in Luke 9, he performs exactly such an act, in a way that is meant to evoke the giving of manna. Jesus responds to the Devil’s challenge, but entirely in his own way, and in his own time.

Then they go up to a high place.

After that miraculous feeding, Peter acknowledges Jesus as the messiah. There then follows another reversal of the wilderness episode. The Devil had “led him up to a high place” to tempt him with worldly power. In Luke 9, it is Jesus who takes the initiative in “leading people up” when he takes his apostles “up to a mountain.” There he is transfigured in divine glory, and appears with Moses and Elijah, as God proclaims his Sonship. Again, this scene reverses the earlier one. Jesus will indeed go up to a high place where he will receive immeasurable power, far beyond mere kingly rule, and he will achieve it through his obedience to God, not Satan.

And then, third, they quote Psalm 91, and this time, they do it in full.

We then move directly on to Jesus’s sending out the disciples, in what is effectively the foundation of the church. Here again, the story overturns an earlier temptation, specifically the Devil’s use of Psalm 91. Jesus sends out his seventy-two disciples (or seventy; manuscripts differ), with healing as a core part of their mission. In each village, they should “heal [therapeute] the sick who are there.” At the time, the boundaries between healing and exorcism were slim to nonexistent, as was the distinction between the sick and the possessed. Jesus is dispatching exorcists, not paramedics. On their return, the disciples joyfully report their triumphs, but they do not mention healing or “therapy” in any sense that we might recognize. Instead, they recount over- coming devils, daimonia:

And the seventy returned again with joy, saying, Lord, even the devils are subject unto us through thy name. And he said unto them, I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven. Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you.

In this last verse, 10:19, Jesus is remembering and paraphrasing our psalm’s v. 13. Reinforcing the identification is the assurance that nothing will hurt the believer, which recalls 91’s “no evil shall befall thee.”

The Great Reversal

Over the previous two centuries, Jewish interpretations of v. 13 had transformed the psalm’s animals into threatening spiritual beings and demons, and that exactly fits the context here. One phrase here can be interpreted in various ways. The Greek text of Luke 10:19 promises triumph over “the power of the enemy,” ten dynamin tou echthrou. But what does that last word, echthros, mean here? Literally it means an enemy, a hostile force or person, and that is how it is rendered in most English translations. It is the word used when Jesus tells his followers to love their enemies. But it can also mean The Enemy, in the sense of the Devil. (The Greek text gives no clue about issues of capitalization or punctuation.) As this text was interpreted in later centuries, that “enemy” became ever more explicitly Satanic.

We are not told the means by which the disciples undertook their healing of body and soul, still less the exact words they used, but in the context of the passage, it would make excellent sense if they were deploying 91, perhaps as part of a package of other songs and formulae. Within a generation of the events described here, the Qumran community was recording such songs of exorcism, and quoting them alongside Psalm 91. If in fact Jesus’s followers had undertaken their healing mission by deploying 91, it would be exquisitely appropriate for Jesus to reassert that text in praising and reaffirming their victories. For Luke, Jesus is accepting the Devil’s original challenge and overcoming it. Satan had invited Jesus to plummet from a pinnacle of the Temple; instead, he himself has fallen from Heaven. Point by point, the wilderness story has come full circle.

We note that the creatures to be trodden here include “snakes and scorpions,” although the latter does not appear in our psalm. But this does recall a verse in Deuteronomy that stands adjacent to the others cited earlier and which refers to “snakes and scorpions” in the context of the eremos, wilderness. This leaves little doubt that the later passage harks back to the temptation dialogue, and that the two scenes are united by Psalm 91.

Satan is trampled, exactly as foretold in our verse 13, but it just takes a little longer than he, or we, expected.