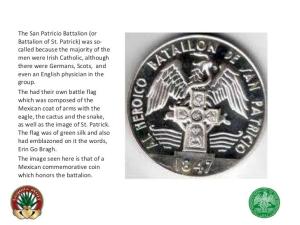

“Los San Patricios” (Pino Cacucci, 2015)

“Have you heard of the San Patricios?” a student asked me a few years ago during an evening Modern Latin American history class; being in ROTC, he was a military history enthusiast and often shared interesting historical tidbits during discussion. I was lecturing on the War of North American Invasion – what we in the U.S. call the Mexican-American War – and we had paused to consider the implications of learning about this conflict from Mexico’s perspective as an unjust invasion of a powerful adversary.

I didn’t immediately recognize that the student was using Spanish words and gazed at him quizzically. “The St. Patrick’s Battalion,” he continued. “Irishmen who left the U.S military to fight for Mexico during the war. They shared the same faith and I think that had something to do with them switching sides to fight against the U.S.”

I had never heard of the San Patricios and I was intrigued. I told the class I would look it up, I would learn more about it and add it to my next lecture on the War of North American Invasion. But as happens so often, life moved right along, and I left APU before teaching that class again.

Having my blog post fall on St. Patrick’s Day has provided both a timely reminder and an ideal opportunity to revisit this fascinating tidbit in history, which, I discovered, the U.S. government successfully hid from public knowledge for nearly a century, not releasing records until the 1970s. Indeed, between 1886 and 1915, letters inquiring about the existence of a contingent of Irish deserters met with denial, the government insisting that no official records existed to confirm such an incident.

Memorial in Mexico City

“In memory of the Irish soldiers of the heroic St. Patrick’s Battalion, martyrs who gave their life for the sake of Mexico during the unjust North American invasion of 1847….

With Mexico’s gratitude 112 years after their sacrifice.

September 1959”

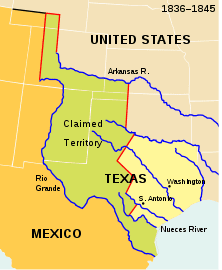

Being a native-born Texan, I share in the history of this conflict, given that a dispute about the borders of Texas incited the war. Formerly part of New Spain, and then Mexico after it declared its independence from Spain in 1810, Texas declared its own independence from Mexico in 1836 before joining the Union in 1845. My family, the Gutiérrezes, arrived to New Spain in the late colonial period with a land grant to colonize the north, settling in what is today Zapata near the U.S.-Mexico border. The local cemetery reveals scores of my ancestors laid out in a veritable history lesson. As I always reply when people ask when my family came to the U.S. from Mexico – we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.

Had the border been established at the Nueces River rather than the Rio Grande, our family history would be considerably different, on both sides. The Gutiérrezes would have remained Mexican, and my mother’s father, fleeing the lingering violence of the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century, would have settled deeper into today’s Texas, so that my parents, separated by an international border, might never have met.

Many are familiar with the context, from the U.S. perspective, of the Mexican-American War, but perhaps not so familiar with the context of la intervención estadounidense en México (United-Statesian intervention in Mexico), typically translated as the War of North American Invasion, from Mexico’s perspective. I cannot detail the complexity of the war’s causes in this post, but as a brief overview, in 1821 – the same year Mexico secured its independence and Agustín de Iturbide proclaimed himself Mexico’s new emperor – Mexico granted permission for Stephen F. Austin to settle 300 Catholic families in Texas (he brought mainly Protestants). In 1823 – the same year that Iturbide abdicated – the U.S. issued the Monroe Doctrine, ostensibly ending European expansion into the Americas. Given the increasing number of U.S. settlers in Texas, John Quincy Adams offered $1 million for Texas in 1826, but Mexico declined. The issue of slavery sparked tension between the two nations, as U.S. settlers continually violated Mexico’s ban on slavery via illegal importation. Foreign interests would become so strong in Texas, in fact, that when Mexican President Vicente Guerrero freed all slaves in 1829, Texas obtained an exemption.

By 1830 – the same year President Andrew Jackson offered $5 million for Texas – 30,000 U.S. immigrants had overwhelmed the Tejano population, prompting Mexico to outlaw further U.S. immigration (a law they repealed a few years later). Grumblings between foreigners and Mexicans continued, a situation exacerbated by Mexico’s political instability, which fomented rebellions throughout the country. In 1836, following the battle at the Alamo and the subsequent capture of General Antonio López de Santa Anna (who had served as Mexico’s president in 4 brief stints between 1833-1835), Texas secured its independence. Intermittent battles continued while both Mexico and anti-slavery forces in the U.S. opposed Texas’s annexation as a slave state, but to no avail, as in 1845, Texas joined the Union as a slave state. The U.S. established the border at the Rio Grande River, with Mexico claiming that the Nueces River, 100 miles east, demarcated the border.

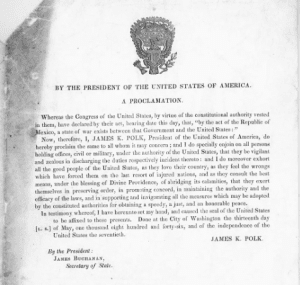

Unable to reach a resolution, James K. Polk declared war on Mexico in 1846, a war that was largely unpopular. Abraham Lincoln, a recently elected congressman, questioned Polk’s motivations for declaring war; you can read that document here. Ulysses S. Grant, who served in the conflict, called it a most wicked war waged by a stronger nation against a weaker one and admitted that he was opposed to the measure, but that he had lacked the moral courage to resign. Henry David Thoreau famously refused to pay war taxes during this period and was briefly jailed.

U.S. declaration of war against Mexico: May 13, 1846

Which brings us to the Batallón de San Patricio, Irish soldiers in the U.S. Army who defected to fight for Mexico under a green banner emblazoned with St. Patrick, a shamrock, and the traditional harp of Erin, and who, after being captured, suffered execution as traitors. What would motivate these men (which included German Catholics and U.S. soldiers) to switch sides?

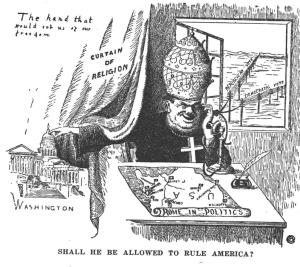

There are several factors, including Manifest Destiny, suspicions against immigrants, a shared history of aggression from a powerful neighbor, incentives/propaganda from Mexico, little to no access to Mass for Catholic soldiers in the U.S. Army, and general anti-Catholicism, the latter about which I learned years ago with fellow blogger Philip Jenkins when I took his wonderful class on American Catholicism while a graduate student at Penn State.

There’s not enough space to analyze these factors, so I’ll just make a few comments. The 1840s saw millions of Irish fleeing famine and the disillusionment of English occupation. Many emigrated to the U.S., where they encountered anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment, suspected of seditious loyalty to the Papacy. This was a period of nativism that saw an armed Protestant mob burn an Ursuline convent outside Boston in 1834, the publication of tantalizing “tell-all” books about life in a convent, and anti-Catholic riots in Philadelphia in 1844 that attacked Irish-American homes and burned Roman Catholic churches.

Anti-Catholic cartoon from the 1840s

Into this atmosphere emigrated John Riley from County Galway in 1843, he who would eventually lead the San Patricios. Having served in the British Army, he joined the U.S. Army in 1845 – the same year Texas entered the Union – where he witnessed his fellow countrymen punished for trivial offenses and his previous military experience overlooked. War with Mexico was imminent, and in April of 1846, camped across the Rio Grande with his company of mostly Irish and German Catholic soldiers, he asked permission to go to Mass (soldiers stationed on the border often crossed into Mexico for Mass), and defected. Others followed and eventually he was leading the Batallón de San Patricio, by most accounts a superb artillery unit. They fought so well that Mexican General Francisco Mejia reportedly said they were worthy of immeasurable praise for their daring bravery.

By 1847, the Batallón de San Patricio consisted of two units of 200 men each. On August 19, they initially repelled U.S. forces outside the walls of Churubusco near Mexico City, but the incompatibility of the munitions with the Mexican rifles and the unintentional explosion of newly-arrived ammunition forced the San Patricios and their Mexican comrades to retreat behind the walls of the convento. According to several sources, each time Mexican officers began raising a white flag, the Patricios tore it down. New Orleans correspondent George Kendall supposedly wrote (I could not corroborate the source): “The boldest in the holding out were the deserters of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, who fought with desperation to the last, tearing down, with their own hands, several of the white flags hoisted by the Mexicans in token of surrender.” Sources differ in their interpretation – some arguing that the San Patricios were so valiant that they were willing to fight to the death, and others contending that they were willing to die in battle rather than face capture and execution by the U.S. Army. The two interpretations may not be mutually exclusive. In the end, a U.S. captain raised his own white handkerchief to stop the carnage. About 60% of the San Patricios died that day at Churubusco, with 85 soldiers, including Riley, captured and sent to trial; the U.S. Army charged 72 with desertion. Mexico’s General Antonio López de Santa Anna apparently declared that with a few hundred more San Patricios, he would have won the war.

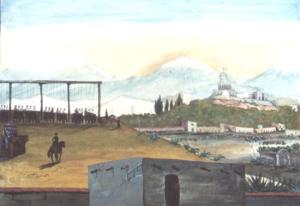

The Battle of Churubusco with a view of the convento

At their trial, most San Patricios pleaded drunkenness, or insisted that Mexico forced them to switch sides, telling detailed stories about their capture. In the final count, the U.S. Army executed 50 San Patricios by hanging over three days in three different locations – the largest mass execution in U.S. history. The final group of 30 were placed on the gallows outside Chapultepec Castle and forced to wait for hours until the moment the U.S. hoisted the flag over the castle in victory, so that as they died by hanging it would be the last thing the San Patricios saw. The cruel nature of the punishment made headlines around the world, including in a Mexican paper: “… these are the men who call us barbarians and tell us that they have come to civilize us… May they be damned by all Christians, as they are by God.”

The mass hanging of San Patricios, as portrayed by Samuel Chamberlain, c. 1867

Riley, among others, escaped death because he had defected prior to the official declaration of war. Along with the surviving deserters, he received 50 lashes and was branded with a D on his face before being forced to bury his friends and then march to prison. All the San Patricios remained imprisoned until June 1, 1848, released as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo.

According to an uncorroborated online source, Riley later wrote about his defection: “Listening to the advice of my conscience for the liberty of a people which had war brought on them by unjust aggressors… I separated myself from the American forces.” Some will argue that Riley – and others who followed him – found it unconscionable to support a Protestant army invading a Catholic country, that they shared more commonalities with the poor working class in Mexico than their fellow soldiers, and that they felt affinity with Mexican believers with whom they could worship in Latin, the universal language of the Catholic Church. Others argue that the Irish could not remain enlisted with a formidable invading army, motivated by Manifest Destiny, attacking a weaker foe because it reminded them of British occupation and famine in their homeland, from which they had fled. Still other sources argue that Mexico’s efforts to recruit soldiers to their side with land grants and promotions in the Mexican military enticed the defections.

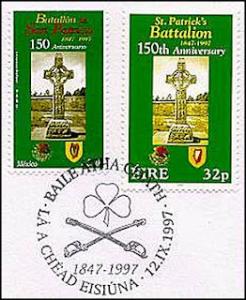

Today, September 12 remains an important day of remembrance in both Ireland and Mexico. In John Riley’s birthplace, the town flies a Mexican flag, while Mexico commemorates the day with music, parades, and other festivities. On the 150th anniversary of the execution of los San Patricios, that is, on September 12, 1997, Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo led a ceremony in Mexico City declaring that there were deep affinities between the Irish and Mexican character. You can read the document here. Both countries issued matching commemorative stamps marking the 150th anniversary.

Commemorative stamps issued in 1997 by Mexico (left) and Ireland (right) to honor the 150-year anniversary of the St. Patrick’s Battalion

While I admittedly have a lot more to learn about the Batallón de San Patricio, as a Mexican Catholic who enjoys the Traditional Latin Mass, I really like the image of Irish Catholics and Mexican Catholics kneeling together in prayer, united by shared faith and personal experiences.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day! ¡Feliz día de San Patricio!