The number of religiously unaffiliated people has risen significantly over the past few decades, a fact that has been the focus of much commentary and collective handwringing about the future of religion and the impact of non-affiliation on civic engagement, pluralism, and American democracy.

The number of religiously unaffiliated people has risen significantly over the past few decades, a fact that has been the focus of much commentary and collective handwringing about the future of religion and the impact of non-affiliation on civic engagement, pluralism, and American democracy.

But non-religious people themselves have received comparatively less consideration in both religious studies scholarship and the public discourse. Who are these “religious nones,” and how have they navigated their decision to be non-religious in the context of a culture and a society that is so deeply shaped by Christianity? How have they reimagined the meaning of community, belief, ritual, and tradition? How have they put values of secularism into practice?

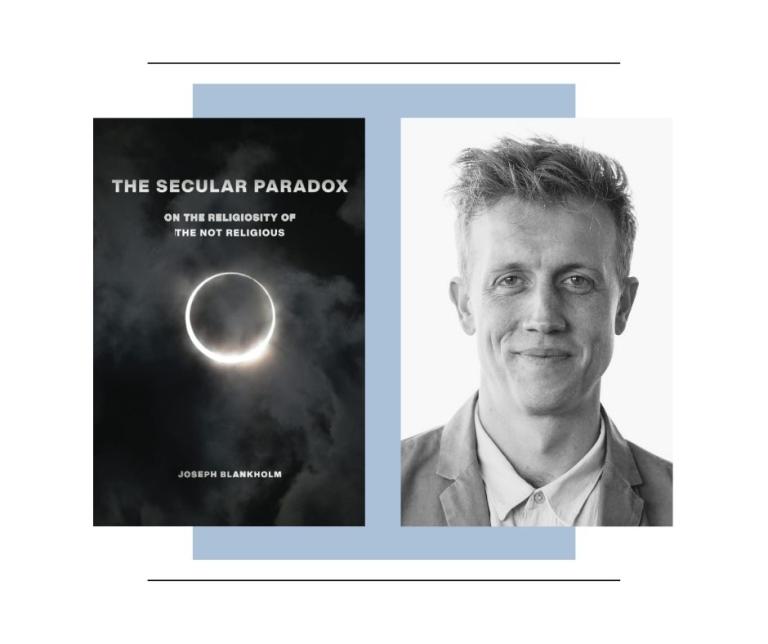

On these questions and more, Joseph Blankholm, a sociologist of religion and a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, offers a much-needed intervention in our conversation about non-religious people. In his book, The Secular Paradox: On the Religiosity of the Not Religious (NYU, 2022), he shows that non-religious people often behave in surprisingly religious ways, in large part because of the strong presence of Christianity in both the broader culture and the secular tradition itself.

I met with Blankholm this month to discuss The Secular Paradox and his research on secularism and non-religion. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Melissa Borja: I think the most useful place to begin is how you came to write about the topic of secularism. Tell me the story behind this book.

Joseph Blankholm: Thanks for this conversation. It’s nice to talk with you about this volume that I’ve spent years researching and writing and I’m excited to share with people. So, the story for this book: I backed my way into it. The story begins when I was an undergraduate. I was studying comparative literature, which in the United States usually means continental philosophy and critical theory. A lot of that is a critique of the Enlightenment, and so some of the texts we’re reading are things by Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche. But we were also being given theological texts that were criticizing Enlightenment thinkers and the way in which Europe produced this secular culture and secular thought.

I was also interested in politics. I ended up pursuing a PhD in anthropology at UC Irvine, where I studied evangelicals in Zambia. I was really interested in doing that because I was interested in evangelicals in the United States and their influence on politics, but also because Zambia is the only officially Christian country in Africa…

I switched, and I started studying separation of church and state in the United States. I started doing an anthropology of atheism and atheists, and I was still studying secularism and studying separation of church and state. But instead of thinking about Zambian evangelicals in a Christian nation, I was thinking about secular Americans who feel oppressed by the Christianity of their state, even though it’s ostensibly secular. Those dynamics proved to be really, really fascinating for me, and as I started to pull the threads more and more, this sweater that I was wearing started to come undone.

MB: I love the metaphor of the sweater you were wearing and it coming undone. Could you talk a little bit more about the specific arguments of your book?

JB: The core of the book is really an argument that secular people are part of a tradition, and that tradition is a lot like a religious tradition. And if we’re scholars of religion, we have pretty good tools for studying and understanding it. From there I make a lot of smaller arguments that prove and also contextualize that and help us think through the consequences of that key insight.

Each chapter is built around a different aspect of religion toward which secular people are ambivalent. So, the first chapter is about belief, the second chapter is on community, the third chapter is on ritual, the fourth chapter is on conversion, and the fifth chapter is on tradition.

The argument is basically that secular people–people who are atheists, agnostics, freethinkers, humanists, secular humanists–share a belief system that is really based in science. I call them exclusive empiricists because a lot of Christians believe in science too. But what separates secular people is they don’t also believe that scripture is a good way of knowing the world. They don’t also believe that divine revelation is possible. So they’re exclusive empiricists, and they’re also people who believe in their own finitude. They think that consciousness and entire life just ends at death, and that’s really all we have. A lot of them are also, I guess you’d say, ontological materialists or physicalists. They have certain beliefs that maybe they hold lightly, but live as if they’re true, that this is all a material substance.

So those are basically the beliefs of nonbelievers, and it’s the central part of their identity. And then I studied people who are forming [secular] communities, local communities around the country, people who are joining national organizations that do everything from lobbying to activism to legal work. Some of them are much more focused on things like pastoral care. There are national organizations that help the local communities do good accounting, get tax exempt status sometimes as a religious community, because the IRS will accept that, help them deal with aging “congregants,” essentially, for lack of a better term. And so [there are] different types of national and local work that nonbelievers are engaged in as nonbelievers—people who share this belief system working together to do different kinds of things.

It turns out also they have rituals. They get married, they have memorial services, they have coming of age ceremonies, they have naming ceremonies. And a lot of these are modeled on Christian or other religious ceremonies. But what they mean and how they’re structured are really oriented toward secular people for their understanding of death and the finitude of their life and toward what they think of as meaningful.

Conversion is similar. You know, it’s a huge question for secular people: Am I just deconverting? Sometimes that’s the case. But a lot of times people are also converting to something. They’re gaining this belief system that I’ve outlined and shown as present. Then they’re wondering, Do I want to join a community that is similar in some ways to the religious community I was a part of because now I have kids, and I want to send them to something like Sunday School, or I want intergenerational community for my children, or I really like that I went to a Christian summer camp, so I want to send my kids to a secular summer camp.

Then the tradition chapter is really thinking, where does this all come from? It’s very easy to trace for hundreds of years. It’s harder to trace for thousands, but I think you can do it. So if you trace it for hundreds of years, you look at the French materialists in the late 1700s and the secular religions in the wake of the French Revolution pretty concretely—that’s the same stuff that we’re seeing today when I’m doing anthropology of secular people. It passes through August Comte’s fantastically interesting Religion of Humanity in the middle of the 19th century, all the way into how that influences humanism and the way it integrates with the Unitarian Church in the early 20th century. It undergoes these changes, but you can see there’s a concrete chain of influence—people publishing, people founding publishing houses and founding newspapers—and that history is really easy to trace. The deeper history is harder, but I trace some of that too, and I think it’s pretty interesting.

The big point is that secular people are an awful lot like a religious tradition, if we choose to look at it that way. And that tells us an awful lot about who secular people are. They’re not just the remainder of religion. They’re not just this negative—they’re this positive thing. But here’s where it gets really tricky, and this is why it’s a paradox. They’re kind of both. So to be secular is to be not religious and to also be kind of religious in a way that’s hard to talk about, hard to admit, even if you’re really into it, even if you’re someone who’s in these communities.

…I went to a humanist celebrant ritual workshop. It’s basically humanist clergy, and it’s a workshop about how we create effective rituals to mark meaning and time in people’s lives. And I’m in that room with those people and they are drawing hard lines, like I can’t have any God talk when I do a wedding for people [or] I can’t have a cross on the wall when I do a memorial service because they’re not religious. So they’re doing these very religion-like things, but they’re drawing hard lines as well. That feeling of both/and: that’s what it is to be secular, and that’s the secular paradox that I think is quite unique and tells us a whole story about this thing that’s both denied and kind of tentatively embraced.

…I spent a lot of time in the book talking about people I call secular misfits. There are people who mis-fit the secular. The metaphor of a shape that mis-fits is actually really important because it tells us that when you remove religion, it creates a Christian-shaped hole. And when you’re trying to fill that hole, you have to basically participate in what is mostly a European tradition.

…If I’m looking at secular Jews—Jews who are atheists—some of them are forming communities, and some of them are not. I’m looking at people who can’t deconvert like Christians do because you can’t just not be Jewish anymore. I actually interviewed a guy who was really, really upset about this and kept coming back to it in an interview because he wanted to be able to deconvert like his Christian friends could. And, you know, if I’m talking to a Black atheist, I’m talking to people who experience what they call sometimes a double negative. They use different language, and I don’t even know if they’re talking to each other. They just all feel this [frustration] where their own community doesn’t believe you can be Black and atheist because they see Black as coextensive with religiosity, Black bodies as being inherently religious. Then they’re talking to an atheist community where they’re wearing these Richard Dawkins shirts that say, “We’re all African.” They want to erase racial particularism because they believe in a universal human. And so they are experiencing this sort of double negation, this double refusal of their legibility as Black atheists. That tells me a story about the Christian-shaped hole the secular leaves, and it tells me a story about what you need–a certain type of body, a white male body, usually of European descent–to look, feel, and be secular in the normative American way.

Hispanic atheists are another good example I talk about a lot. I also talk about a pair of siblings who are Native American and how they fit these things together being atheist and actively participating in their indigenous traditions in Oklahoma. And so just trying to figure out, okay, there’s this tradition that’s been around for a long time. What does it feel like today to inherit this tradition but also have it negated? How is it differently negated for different people? How is it differently embraced for different people? And then what does that mean for us if we’re going to be, say, scholars of religion, but also just people in the world who are atheist or agnostic or interacting with atheists or agnostics—what are the consequences of all that? I try to do all those different things in the book.

MB: I’m already hearing things that surprise me as a religion scholar. I wonder what most surprised you when you were having conversations with the people who are at the center of your book and doing the research on this topic.

JB: It was a really very self-undoing process. I think I’ve probably considered myself an atheist, but someone who doesn’t really think much about that. For a lot of my life since I was a teenager, I just didn’t have a lot of self-consciousness about it, I think. Doing the research for this book taught me that I’m secular, and it taught me I’m part of a tradition, and it gave me myself in an incredibly disorienting way. And that’s that sweater that I started to pull the threads on and undid, and I’ve had to kind of rebuild and refigure out who I am through that process

…I think that there’s two things that a lot of atheists and agnostics and other kinds of nonbelievers do that I’ve realized maybe I did, but I certainly can no longer think this way. One is thinking that what we believe is what you get when you strip religion away. It’s just what’s left. And the other one is that what we believe is what’s true, and that there are certain ancient people who figured out these truths, and then there was this period we call the Dark Ages, and then it was rediscovered in the Renaissance and rediscovered in the Enlightenment, and now we have that truth again…I think that those are two really prevailing stories that I was disabused of by myself, but also by the people I was talking to and learning from. And the place that’s left to me is a different kind of place. So toward the end of the book, I say, I’ve taken the way the eternity of our truth, but I’ve given us a place in the pantheon, and I use that third person plural to do that work…I hope that my fellow scholars who read [my book] genuinely see themselves and can take a better account of themselves because I think a lot of us go around not really realizing who we are, not realizing we’re part of this tradition, not realizing the way we determine it. And so I’m trying to hand people a piece of themselves.

MB: I love that, and it gives me a lot to think about personally. In general, I’m very fond of people who are willing to say hard truths and encourage people to confront difficult things about which it’s painful to be honest.

We’re also dealing with a broader conversation in general in America about the rise of “religious nones.” Thinking beyond the academy, I wonder if you could talk about how your book intervenes in the broader public conversation about non-religious people. What do you think the broader public gets wrong when they talk about non-religious people? And how does your book offer an important corrective?

JB: It’s a good question. It’s a lot of what my new work is focusing on because it just builds sequentially. So when I have like a new PhD student who comes in to work with me, there’s usually a point in the first few meetings where I tell them, “You’re in the weeds,” and I mean something really specific by that.

So I’ve come to understand that for American religious pluralism, a garden is a pretty good metaphor. It’s something that’s tended to somewhat violently. Sometimes you’re using pesticides, and you’re killing things. There are certain cultivars that you’ve selected through a process we might liken to eugenics, and you’re ordering it neatly in this array and selecting for certain traits and all that stuff. And there are certain things that you recognize as vegetables and flowers and other types of plants, and you kill all the weeds. Well, now we’re at a point where a third of the country is weeds because they’re not religiously affiliated. They’re doing all kinds of things that don’t look like religion. They don’t look like the plants we’re used to. They’re not doing what they’re supposed to do. And we need to start figuring out how to identify these cultivars because our garden is overrun by weeds, and we don’t have the thinking to do that yet.

And so in my first book, I’m taking off this small chunk, right? Atheists, agnostics, humanists, other freethinkers: those are some weeds. I think we also need to understand spiritual people and the variety among them better. We need to understand the metaphysical tradition. And then I think we also need to make better sense of people who are a little bit incoherent in terms of their beliefs and maybe are incoherent because it’s kind and sweet and loving to be that way. It creates more social cohesion if you’re not getting into arguments about what’s real or how best to know the world or something like that. So a lot of the new work I’m doing is kind of making sense of the weeds, and I think it also makes sense to call them weeds because think about the terms that we use, right? The non-religious, the nones, atheists, agnostics: they’re all defined with respect to the religious. That’s what kind of term “weeds” is, but with respect to plants. And so we’re overdue. I’m in the weeds, my students are in the weeds, and we need to figure out what we’re looking at.