The story has been repeated so many times that it’s now one of the most familiar in the history of white evangelical politics.

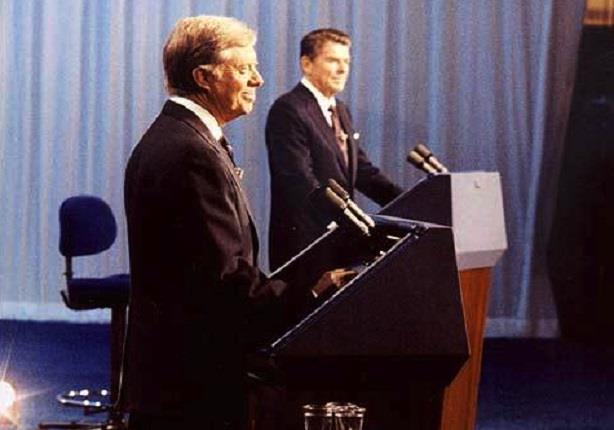

It goes like this: White evangelicals voted for Jimmy Carter in 1976 because they were convinced that the born-again Southern Baptist deacon was one of their own. Sometime between 1977 and 1980, they decided that something – maybe abortion, gay rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, “secular humanism,” or an IRS civil rights directive that would affect Christian private schools – was seriously wrong with the Carter administration, and they therefore repudiated Carter and voted for the Republican candidate Ronald Reagan in 1980. They have been voting Republican ever since.

While historians of the Christian Right have spent many years debating exactly which issue prompted evangelicals to switch from Carter to Reagan, few seriously questioned the central premise of this narrative – that is, the assumption that the switch actually happened. In fact, I’ve assumed as much myself.

That assumption is not entirely wrong; there really was a shift of some evangelical votes from the Democratic to the Republican column between 1976 and 1980. But the shift was less pronounced than one might imagine, given all of the coverage that this supposed transfer of evangelical partisan allegiance has received over the past four decades.

In actuality, when four of the leading political scientists studying modern American religion and politics – Lyman Kellstedt (Wheaton), John Green (Akron), Corwin Smidt (Calvin), and James Guth (Furman) – analyzed polling data from the National Election Study in the early 21st century, they found that the white evangelical presidential vote shifted from 51 percent Republican in 1976 to 65 percent in 1980. In other words, it appears that although there might have been a little bit of party-shifting going on, it was fairly minimal; at most, there was a net shift of only about one in every seven evangelical voters from support for Carter in 1976 to support for Reagan in 1980.

In short, there was far more support among evangelicals for Ford in 1976 than is often remembered today, and there was likewise far less support for Reagan in 1980 than people often imagine.

Kellstedt and his colleagues published their analysis of historical evangelical voting patterns in 2007 (it was included in the second edition of Mark Noll and Luke Harlow’s Religion and American Politics), and I’ve known about it ever since that moment. I even cited the study in God’s Own Party (2010).

If someone had asked me at any point in the past fifteen years how many evangelical voters supported Reagan in 1980, I would have said (correctly) that it was about two out of three – a percentage that was a bit lower than the number who supported the Republican presidential candidate in any subsequent presidential election. Indeed, compared to the last few presidential elections, when about 80 percent of white evangelical voters can be expected to cast their ballots for the Republican candidate, 65 percent evangelical support for Reagan seems remarkably low.

But even though I have known all of this at some level, it was not until the past year, when I began doing more research on regional disparities in evangelical political behavior, that I began to think about the implications of this research and to delve more deeply into the question of which evangelicals supported Carter in 1980 – a question that Kellstedt and his colleagues did not address. Who were the one-third of white evangelical voters who cast their ballots for Carter’s reelection?

To answer this question, I want to look at the regions of the United States where evangelicalism was most concentrated at the end of the 1970s. As I argued in a recent Anxious Bench blog post, when we study modern American evangelical political behavior, it’s best not to think of white evangelicalism as a monolith but instead to view it as a coalition of three distinct regional groups: Midwesterners, Sunbelt suburbanites, and rural southerners.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, the intellectual center of Midwestern evangelicalism was the Chicago suburbs, where Wheaton College was located, Christianity Today was headquartered, the National Association of Evangelicals was founded, and several leading evangelical publishers (such as IVP, Tyndale, and Crossway) were located. Grand Rapids, Michigan, the home of Calvin College (now Calvin University) and publishers such as Zondervan and Eerdmans, competed with suburban Chicago as a second regional center of Midwestern evangelicalism, albeit with more overtly Reformed leanings.

The politics of these two Midwestern evangelical centers were nearly identical: Both were strongly Republican. With the exception of a very small number of left-leaning evangelicals associated with Sojourners magazine and the remnants of Evangelicals for McGovern, evangelicals in both of these Midwestern regions supported Ford over Carter in 1976 and Reagan over Carter in 1980.

Sunbelt evangelicals, by contrast, were a little more circumspect about their partisan preferences in 1976, but in many cases leaned toward Ford. The central figure of Sunbelt evangelicalism was Billy Graham, who was believed to be a quiet Ford supporter in 1976 but who made a point of keeping silent about his preferences – in contrast to his overt support for Nixon four years earlier. The pastor of the church where Graham was a member, First Baptist Dallas, made a point of endorsing Ford shortly before the election. In general, the leading megachurch pastors or religious broadcasters of Sunbelt evangelicalism gave Carter careful consideration, but then voted for Ford. Jerry Falwell said that early in the campaign, most of the people he knew supported Carter, but after the Democratic candidate’s Playboy interview, he and his associates decided to support Ford.

Graham and Falwell were hardly political anomalies among evangelicals in the upwardly mobile suburban Sunbelt. Sunbelt evangelicals were much less monolithically Republican in the 1970s than evangelicals in the Chicago suburbs or Grand Rapids were, but the evidence suggests that the Sunbelt suburbs where these evangelicals were located often leaned Republican – which likely means that the evangelicals in those suburbs did as well. Campbell County, Virginia, where Lynchburg (the home of Jerry Falwell) is located, voted for Ford over Carter by nearly a two-to-one margin in 1976. Dallas, Texas likewise supported Ford, as did the suburbs of Birmingham, Alabama, and all of the California counties where evangelicals had a sizeable presence, such as San Diego and Orange County. It is true that suburban Atlanta supported Carter (barely), but Carter’s real strength in 1976 came from rural counties, which gave him overwhelming support.

Since Carter’s appeal among evangelicals in the upwardly mobile suburban Sunbelt was limited, he depended heavily on two other groups of southern white evangelical voters: Southern Baptist moderates like SBC administrator Foy Valentine, who had progressive views on economics and centrist views on social issues, and a much larger group of rural evangelicals, who tended to be less progressive theologically but just as strongly Democratic as the moderates. The moderate Baptist leaders were more vocal in their explanations of why they were supporting Carter, but the rural evangelicals provided more votes. Their support was just enough to give Carter approximately half the evangelical vote in 1976 – and a strong majority of the southern evangelical vote, despite the defection of many suburban Sunbelt evangelicals to the Republican candidate.

But what happened in 1980?

The traditional narrative suggests that evangelicals abandoned Carter in droves and voted for Reagan. After all, Reagan made a direct bid for southern evangelical support and numerous southern evangelicals reciprocated with their endorsement.

But, as we have seen, Carter never had the support of many Midwestern and Sunbelt evangelicals – and if that’s the case, the only sizeable contingency of evangelicals who could have switched their votes from Carter to Reagan were those in the rural South. In actuality, relatively few of them abandoned Carter.

Upon closer inspection, it appears that a number of the Christian Right leaders in 1980 – especially Jerry Falwell – had never supported Carter but had instead voted for Ford in the previous election. Furthermore, reports from the early 1980s indicate that the Moral Majority’s center of influence was concentrated in the Sunbelt suburbs, such as the area around Birmingham; it did not attract as many members in rural areas.

What happened in 1980 is not, therefore, that large numbers of evangelicals who had voted for Carter in 1976 regretted their action and cast their ballots for Reagan in 1980. Instead, in the suburban Sunbelt that had quietly voted Republican in 1976, evangelicals mobilized and created a new political movement that assigned religious importance to a partisan choice that they and their neighbors were already making.

These Sunbelt evangelicals were, for the most part, upwardly mobile, and they found it easy to embrace a religiously infused political message that melded the culture wars and free-market economics – because, for the most part, they were either already Republican voters or they were part of a region and social class that was already in the process of embracing a Republican identity.

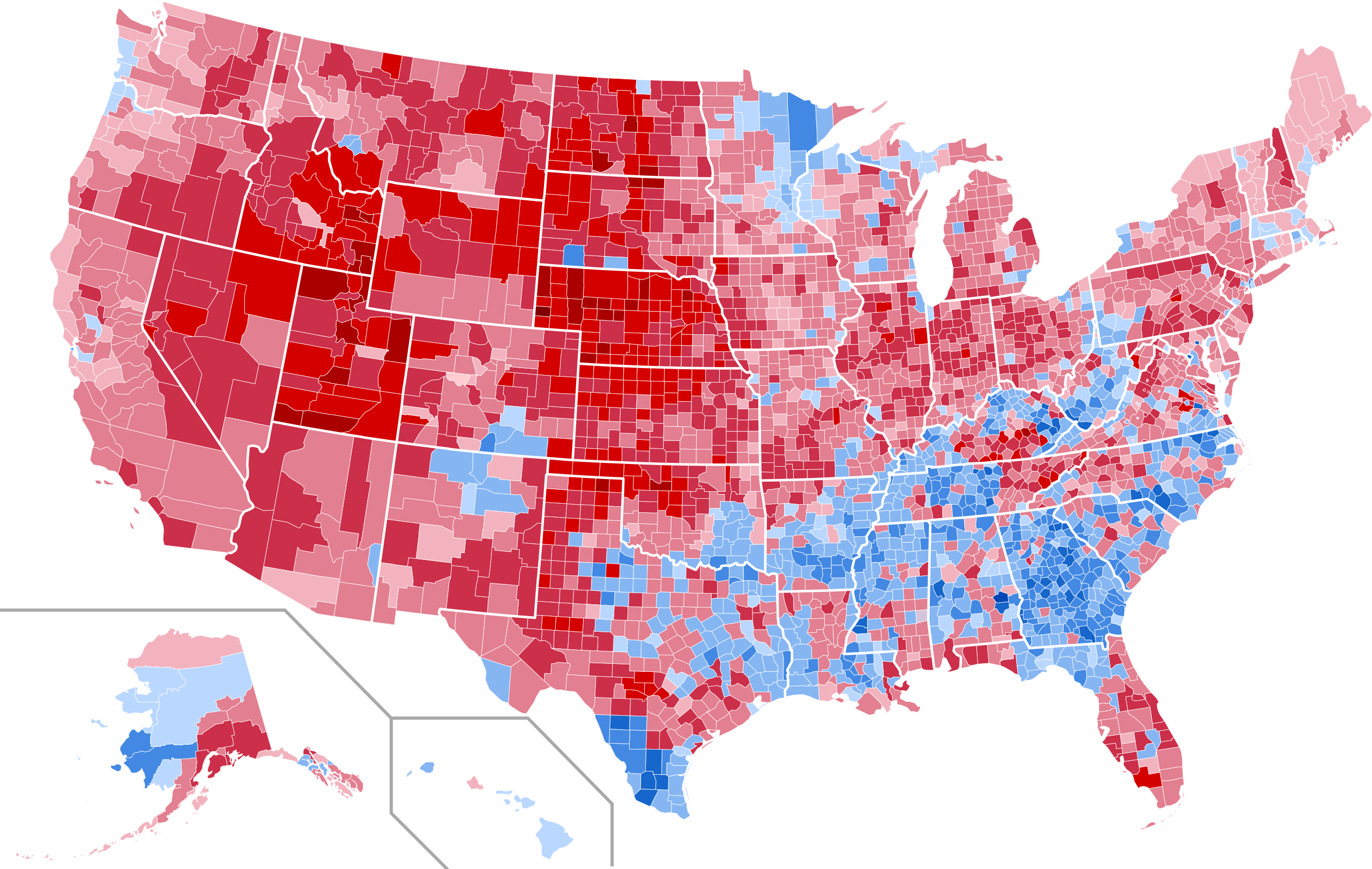

But in the rural South, evangelicals didn’t buy this message. Take a look at this election map from 1980:

This map shows that while Reagan won many of the southern metropolitan areas, including Birmingham, Pensacola, Mobile, and a few of the Atlanta suburbs, the rural South mostly went to Carter. The rural west Georgia county where I currently live (Carroll County) voted for Carter over Reagan by 56 percent to 40 percent.

While Georgia (which, after all, was Carter’s home state) might have been more likely than the rest of the South to remain loyal to Carter, this phenomenon wasn’t confined to Georgia. Carter carried the state of West Virginia. He won most of the counties of middle Tennessee and Arkansas. And although Reagan had launched his presidential campaign in Mississippi with a direct bid for southern white votes, Carter came remarkably close to winning the state; Reagan ended up carrying Mississippi with only 49.4 percent of the vote, compared to Carter’s 48.1 percent.

In short, there’s substantial evidence that a lot of southern whites (including southern white evangelicals) in the rural South quietly voted for Carter in 1980, despite all of the encouragement of the Sunbelt-based Religious Right not to do so.

But the rural southern evangelicals who voted for Carter over Reagan didn’t say a whole lot about it. The Carter campaign’s attempts to organize an evangelical vote against Reagan didn’t go very far, and there was no rural southern evangelical organization for Carter that could counter the media influence of the Christian Right.

Perhaps one reason for the silence was that the southern rural evangelical support for Carter in 1980 was based not on any specific issue but rather on something a bit more nebulous: a perceived set of shared southern values and a belief that Carter cared about the poor white southerner in a way that perhaps the Republican Party did not.

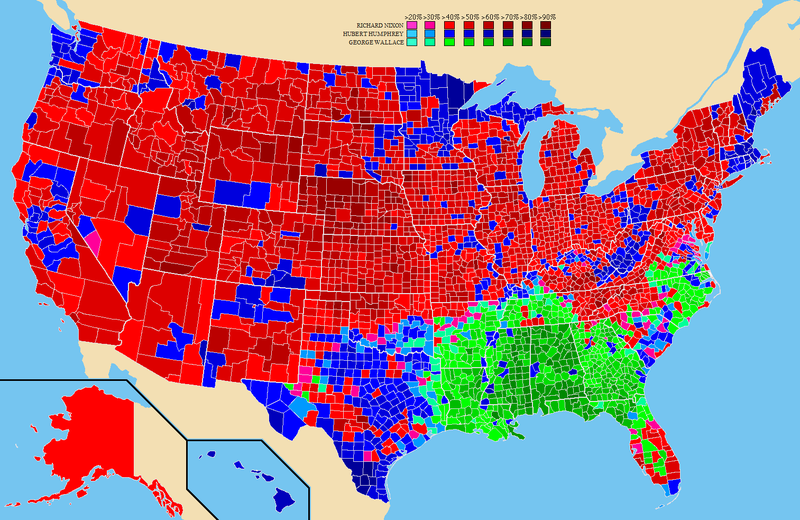

Indeed, the map of rural southern counties that supported Carter in 1980 shares a remarkable correspondence with the 1968 map of rural southern counties that voted for George Wallace (whose votes are marked in green on this map):

A typical rural, predominantly white county in the South voted for Wallace in 1968, Nixon in 1972, Carter in 1976, and quite possibly Carter again in 1980. But then the county switched to Reagan in 1984 and Bush in 1988. Although some rural southern counties supported Clinton in the 1990s, they returned to the Republican fold in 2000 and never went back to the Democrats.

But in 1980, their votes were still in flux – and even in the midst of a Reagan landslide, they remained remarkably loyal to Carter.

This matters for at least two reasons.

First, I think that it suggests that the origins of white evangelical support for the Republican Party are considerably more complicated than many analysts have suggested. Various regional factions of evangelicals have moved in and out of the conservative Republican coalition at different points over the course of the last half century – and in 1980, the evangelicals who were moving into that coalition were largely suburban; they were not rural southerners. They were already predisposed to favor the Republican Party’s free-market ideology and its color-blind ideology.

But second, it tells us that we’ve ignored a critical evangelical constituency when we’ve told the story of the 1980 election only as the story of a massive evangelical conversion to the GOP. We’ve left rural white evangelicals out of the story. And it turns out, on closer inspection, that these were the very voters who had been most drawn to George Wallace’s campaign a few years earlier.

Carter’s policies on civil rights were very different from those of Wallace. Yet his appeal to rural white southerners may have been similar. Like Wallace, he could credibly claim to be one of their own. He could plausibly claim to understand the rural South. And white voters in the South were not going to take that lightly. It would take a lot to convince them to vote against a fellow white rural southerner – and many of them were not ready to take that step in 1980.

White rural southerners did not become devoted to the GOP until they became convinced that the party shared their values and represented their identity. They weren’t yet persuaded of that in 1980. Reagan represented the values of the conservative Southwest, but it was not yet clear to many rural whites in the South that he represented the values of their region. And so, for at least one more time, they voted for a Democrat in a presidential election.

Forty years later, rural whites in these same counties overwhelmingly supported Donald Trump. If we want to understand the Trump phenomenon among evangelicals in the rural South, it’s not enough to study the political behavior of the Sunbelt evangelicals who organized the Religious Right at the end of the 1970s and voted for Reagan in 1980. Instead, if we’re looking at evangelical political preferences in 1980, we need to look not only at the Reagan voters but at the Carter voters – because it’s from the very counties that gave the strongest support to Carter that some of the most enthusiastic Trump voters would emerge.

Carter and Trump are wildly different, both in character and in their positions on the issues. But as strange as it may seem, the through line for rural southern voting runs from Wallace to Carter to Trump – just as for the suburban Sunbelt it runs from Nixon to Reagan to Biden.

The history of white evangelical politics, it turns out, is not always quite what we have imagined it to be. The story that we’ve traditionally told about the origins of the Religious Right and their affinity for Reagan is partly true – but it’s an incomplete story, because it leaves out the rural South and focuses too heavily on the Sunbelt.

The suburban Sunbelt evangelicals, who had never had much affinity for Carter, soundly repudiated him in 1980. But rural southern evangelicals did not. And if we want to understand evangelical political behavior, we need to figure out why.