Yesterday, as I was enjoying a light breakfast of fried eggs, toast, and a Nesspresso cappuccino in our kitchen, I stumbled upon the most curious tweet. Initially when I saw the tweet, I became puzzled. Why? Well, the tweet consisted of a quote attributed to Jonathan Edwards, along with a portrait depicting a youthful, handsome, man composing a document at a stationary desk. While the portrait depicted a genteel man from the eighteenth-century, I knew it certainly was not a portraiture of Jonathan Edwards. There are only a few authentic, historical, semblances of him; I am familiar with all of them. It was clear to me that this portrait was inauthentic. Obviously, the negligence of using an inauthentic depiction of the quote author, understandably, might be inadvertent. Nonethless, it niggled me enough to re-read the quote rather than to just keep scrolling through my feed.

The quote seemed to be charged intentionally with the sort of idea that would evoke vitriol from readers. It said: “To pretend to praise Christ while living lives that mock Him is like joining those who taunted him at the crucifixion and shouted Hail, King of the Jews.”

The quote tweets and comments from others candidly pointed out to the original poster the hypocrisy of the assertion attributed to Edwards, a known slave-holder. For those less familiar with this point of fact, both Yale and Princeton have documented Edwards’s status as a slaveholder and his views on slavery. Interestingly, the original post came to my attention because the Oklahoma University sociologist, Dr. Samuel Perry (@profsamperry), had quote tweeted and commented: “And after he penned these words, Jonathan called for one of his slaves to bring him more ink for his quill pen so he could continue calling Christians to live like Jesus.”

I then started to speculate to myself about whether Edwards had indeed penned these words. In my time on social media, I have observed a number of misattributed quotes to great minds of Western history. Since I happen to be a scholar of Jonathan Edwards, I was able to make short work of authenticating the quote, and here’s what I found.

The quote was an inauthentic attribution to Jonathan Edwards!

Here’s how I went about my fact-checking. First, I visited Edwards.yale.edu and performed a Quick search from the sites home page. Years ago, the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale, under Kenneth P. Minkema’s leadership, digitized all of Edwards’s writings, even making original manuscripts available to readers with high resolution photography. I simply entered the word “mock” from the quote into the quick search and pulled 128 hits from the 73 volumes of Edwards’s digitized works. (You may view the results here.) I combed through those hits and discovered that none of them were a match, not even a close match, to the tweet quote.

Knowing that many of Edwards’s sermons, after the 1740 revivals, were produced in outline format, I thought that perhaps the quote derived from a cleaned up sermon manuscript that had been prepared for a critical publication. I happen to have the entire critical collection of Yale’s The Works of Jonathan Edwards on Logos, so I opened each work and searched again for the term “mock.” Still nothing.

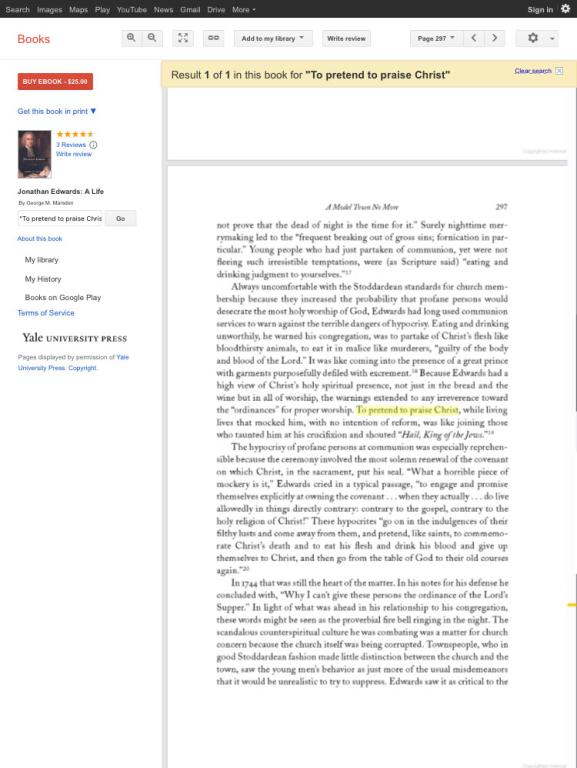

I then decided to simply Google the first phrase of the quote, “To pretend to praise Christ…”, and I found a revealing hit on Google. Google detected the phrase on page 297 of George Marsden’s acclaimed biography, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (Yale, 2003). However, these were George Marsden’s words describing the ideas of Edwards rather than a direct quotation to Edwards.

There happened to be an endnote for the quote, so I consulted that endnote on page 563. There Marsden cites that the ideas he is working with in this chapter are derived from a sermon published in 1788 from Edinburgh that appears in Volume 2 of the Hickman Edition of Jonathan Edwards. Naturally, I consulted this volume of Hickman and came across the paragraphs that inspired Marsden’s interpretation of Edwards. Here are those two paragraphs:

Now, what can this be else but mockery, to make a show of great respect, reverence, love, and obedience, and at the same time willfully to declare the reverse in actions. If a rebel or traitor should send addresses to his king, making a show of great loyalty and fidelity, and should all the while openly, and in the king’s sight, carry on designs of dethroning him, how could his addresses be considered other than mockery? If a man should bow and kneel before his superior, and use many respectful terms to him, but at the same time should strike him, or spit in his face, would his bowing and his respectful terms be looked upon in any light than as done in mockery? When the Jews kneeled before Christ, and said Hail, King of the Jews, but at the same time spit in his face, and smote him upon the head with a reed, could their kneeling and salutations be considered as any other than mockery?

Men attend ordinances, and yet willingly live in wicked practices, treat Christ in the same manner that these Jews did. They come to public worship, and pretend to pray to him, to sing his praises, to sit and hear his word. They come to the sacrament, pretending to commemorate his death. Thus they kneel before him, and say, Hail, King of the Jews; yet at the same time they live in ways of wickedness, which they know Christ has forbidden, of which he has declared the greatest hatred, and which are exceedingly to his dishonor. Thus they buffet him, and spit in his face. They do as Judas did, who came to Christ saying, Hail, Master, and kissed him, at the same time betraying him into the hands of those who sought his life.

When I definitively uncovered the evidence proving the misattribution, I was stunned. How could someone make such a careless blunder?

As a scholar of Jonathan Edwards and a public intellectual, I felt a responsibility to set the public record straight, so I crafted a quote tweet thread about the inauthentic attribution to Jonathan Edwards and provided commentary about the context and circumstances of the tweet. For by this time, the original post had accumulated 55k+ views, 525+ likes, and 150+ retweets. Yet, no one, and I mean no one, had thought of authenticating the quote.

The original poster, Justin Bullington (@JustnBullinton) is a micro-influencer with over 24k followers. He is the host of the TheoBros Podcast (@TheoBrosPodcast), and he is a pastor and bible teacher at Princeton Bible Church in Princeton, Illinois, located off of I-80 in the exurbs, just over two hours West of Chicago. I have noted for some time that sometimes pastors at quiet, small town, rural churches have an oversized online presence of influence. There’s actually a number of these sorts of nano-influencers (1k–10k followers) and micro-influencers (10k to 50k influencers), as well as, perhaps, a handful of mid-tier influencers (50k–500k followers) out there with this kind of ministerial profile. It sort of makes sense that pastors of small churches will have the bandwidth to cultivate an oversized social media influence.

Interestingly, when I first stumbled upon the original post and poster, I took him to be your standard Reformed Resurgence TheoBro, which is typically of the covenant amillennial persuasion or the more docile historic premillennial version. However, when ascertaining his church’s distinctives, I discovered that the church he pastors is distinctively of the dispensational premillennial variety, which means it has fairly fundamentalist roots. Perhaps these fundamentalist roots reveal something about the cultural inclinations of Bullington.

Regardless, Bullington has clearly embraced the TheoBro epithet as a badge of honor rather than an opprobrium, and he imbibes the masculine authority that accompanies the emerging tribe of TheoBros.

I rightly indicated in my thread that a negligent misattribution of a quotation, even if unwitting, is not merely irresponsible, but it undermines the trustworthiness of Bullington’s “manly” authority. Retrieving from Bullington’s heritage, I quoted from the Banner of Truth Trusts abridged Puritan Paperback of William Perkins’s famous puritan preaching manual, The Art of Prophesying: “In preparation there must be careful private study” (Perkins, The Art of Prophesying, loc. 405).

I continued my thread with the following pointed comments:

Sadly, too many care about building a platform rather than taking care to study diligently. If you cannot responsibly make a quote attribution, how can we trust you with interpreting and preaching God’s Word faithfully on Sunday.

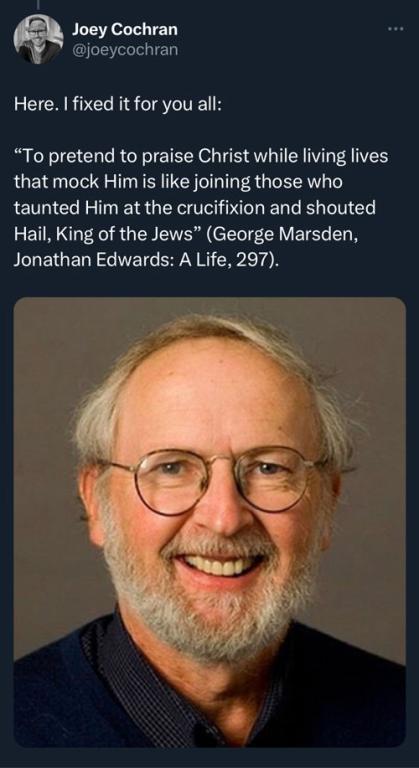

My thread concluded with a common refrain that many social media interlocutors employ. They correct the original post. I did so, by republishing the quote and properly attributing and citing George Marsden, and included an accurate headshot of this highly regarded historian. While a tad snarky, it makes a vital point worth imitating, that is, to give proper attribution to the correct person and to put care into research and study. That way we do not mislead people.

Honestly, it is extremely deceptive for a man to rely on his manly authority as a crutch to camouflage sloppy habits and pass himself off as an expert or authority. In today’s era of ChatGPT, platform over priorities, pragmatism before diligence, and celebrity rather than faithfulness—we need pastors and Christian intellectuals who push back against these impulses and model scholarly care and integrity, practice it, and teach it to the next generation. A number of commenters on my thread indicated the significance of this value.

I was flattered by both Lauren Chastain’s (@laurchas22) and Dr. Carol Ann Vaughn Cross’s (@equipoisecology) kind comments. Lauren insisted that “There should be a whole class in a university setting that goes into the beauty that is this tweet thread.” Dr. Cross indicated that she was bookmarking the thread to use in her Core First-Year Research and Writing Seminar at Samford University. The two of them convinced me that it would be relevant to document and recount this story for my monthly column at the Anxious Bench and to use the incident as a case study in my lectures on historical methodology and research at Wheaton College. Incidentally, I concluded the thread with an invitation to come study with me at Wheaton College.

I’m grateful that the thread I produced affected people. We need to celebrate and affirm people who take seriously God’s Word, God’s history, and God’s people—and devote their lives to modeling, teaching, and instructing others on how to responsibly represent God to the world.