It was a hot summer in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956. The temperature soared to 100 degrees Fahrenheit in August and highs remained in the 90s for weeks.

But what made the summer especially miserable for the African Americans who lived in Alabama’s capital city was their standoff with the city authorities over the issue of racial segregation. Ever since the previous December, the vast majority of Montgomery’s Blacks had refused to ride the buses in protest over the city’s segregation policies on its public transportation and over the arrest of Rosa Parks. The city had fought back. The home of Martin Luther King Jr., the 27-year-old Baptist pastor who was leading the bus boycott was bombed in the early spring. King was also arrested later that year. Segregation on the city’s buses continued, and so did African Americans’ refusal to ride them.

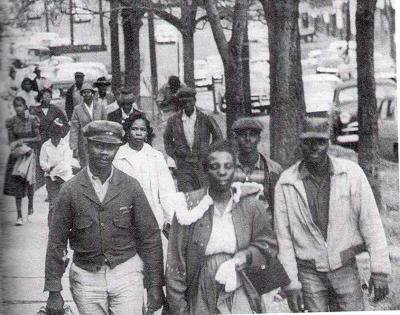

King’s organization, the Montgomery Improvement Association, operated a carpool with 300 cars to give rides to some of the people who had depended on bus transportation to get to their jobs and other places of necessity, but those 300 cars were not enough for everyone who might have needed a ride. And so, all through the long, hot summer people walked. “It is more honorable to walk in dignity than ride in humiliation,” King said. “We decided to substitute tired feet for tired souls, and walk the streets of Montgomery.”

At the end of the year, the Supreme Court would declare Montgomery’s system of bus segregation unconstitutional, and the bus boycott would end with victory for Montgomery’s African Americans, who would be able to ride on newly desegregated buses. But at the end of the summer, Montgomery’s Blacks had no way of knowing when, if ever, this victory would come. And they were tired.

King knew that some of his congregants at the Dexter Avenue Baptist church in Montgomery were probably asking the question of where God was in the struggle. So, in September he preached a sermon about the reasons why he believed in God even in the midst of injustice and the challenges of life.

We don’t often think of King as a Christian apologist. When we think of Christian apologetics, the names that might first come to mind are people like Tim Keller or C.S. Lewis or any number of others who have written books arguing for the rationality of Christian belief or theistic affirmations. King never wrote a book about reasons to believe. But when he stood before his congregation in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956, King offered an apologetic for his Christian faith by outlining his reasons for believing in God even in the midst of adversity.

In 1956, there were several different common approaches to Christian apologetics. Evidentialist apologetics, which relied on historical evidence to demonstrate the historicity of biblical narratives (including narratives of biblical miracles, such as the resurrection of Jesus) and on scientific evidence to suggest that the well-ordered universe must have been created by a divine designer, had been popular since the late seventeenth century, at the dawn of the Enlightenment, and they were still the preferred apologetic approach for some conservative evangelicals. They were the still the leading method of apologetics taught at Wheaton College, where students were expected to take one class in philosophical defenses of Christian theism and another in historical evidence of the Bible’s accuracy – a class that relied heavily on evidence from twentieth-century biblical archaeology.

King never showed any interest in evidentialist apologetics or the classic philosophical proofs of God’s existence that were taught in classes such as those at Wheaton. This was not surprising, since few African Americans had ever gravitated toward evidentialist apologetics or natural theology. All of the books in that field of apologetics had been written by whites, who were asking questions that did not seem to resonate with most African Americans.

But there were other approaches to apologetics that were also common in the 1950s. A few conservative Reformed evangelicals – especially those who were influenced by the theologians and philosophers at Calvin College or Westminster Theological Seminary – were proponents of some form of worldview or presuppositionalist apologetics. Unlike evidentialists, worldview apologists did not try to present evidence to support any particular Christian claim, but instead argued that the entire Christian worldview presented a more coherent picture of the world than the secular worldview did.

Worldview apologetics was closer to the liberal Protestant or neo-orthodox theology that King had learned in his graduate study at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania and Boston University, but liberal Protestants of the time placed greater emphasis than Reformed evangelicals did on the connection between Christianity and democracy or human rights. In their opinion, the Christian worldview was correct not only because it offered the most coherent view of human psychology and human nature but also because it offered the only possible framework for a view of human dignity that was the foundation for human rights and American democracy.

In his studies of Reinhold Niebuhr, the Boston personalists, and other mid-twentieth-century American theologians, King had encountered numerous voices who made some version of this argument. But as he stood before his congregation on a Sunday morning in September 1956 and faced people who had lived with racial segregation and the lack of voting rights for their entire lives – and who had just spent months walking in the Montgomery heat because they refused to endure the indignity of moving to the back of a segregated bus – he knew that the liberal Protestant arguments about Christianity providing a foundation for American democracy would probably sound hollow.

Why should the people in his congregation believe in God? What reason did they have for holding onto their faith in the midst of injustice?

King argued that the reality of evil and injustice gave people even more reason to believe in God. “Real, determined faith in God,” King said, “gives you the conviction that although trouble is rampant, that although you stand amid the forces of injustice, it will not last always because God controls the universe.” The idea of a personal God “gives life a meaning and a purpose that it could never have without Him,” he declared.

“I say that if there is not a God, there ought to be one; and since there ought to be a God, there is a God; and if man doesn’t find the God of the universe, he’ll make him a God,” King said. “He’s got to find something that he would worship and give his ultimate allegiance to. And I say this morning that the Christian religion talks about a God, a personal God, who’s concerned about us, who is our Father, who is our Redeemer. And this sense of religion and of this divine companionship says to us, on the one hand, that we are not lost in a universe fighting for goodness and for justice and love all by ourselves. It says somehow that although we live amid the tensions of life, although we live amid injustice, no matter what we live amid, it’s not going to be like that always.”

The God that King believed the universe pointed to was not merely a spiritual force or the impersonal God of some of the deists. The existence of love and justice in the universe suggested a God who was deeply personal and caring, King believed. “Religion at its best does not look upon God as a process, not as some impersonal force that is a mere moral order that guides the destiny of the universe,” King told his church in Montgomery. “High religion looks upon God as a personality. . . . God is much higher than we are. But there is something in God that makes it so that we are made in his image. God can think; God is a self-determined being. God has a purpose. God can reason. God can love. Aristotle used to talk about God as ‘Unmoved Mover,’ but that’s not the Christian God. Aristotle’s God is merely a self-knowing God, but the Christian God is an other-loving God. He reaches out with His long arm of compassion and love and embraces all of His children.”

But was this merely wishful thinking? The argument that there must be a God because it was the only way to secure love and justice and the higher values of the universe might strike some as circular reasoning or merely a wishful assertion.

But King had one other argument for God that was deeply rooted in the African American Christian tradition: the evidence of personal experience of God. Many of the greatest African American resisters of injustice – people such as Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth – had heard directly from God and had a sense of God’s presence. Anglo-American Christian apologetics was based on the assumption that God’s existence must be demonstrated through reasoned evidence for people who had never sensed God’s presence directly. But what if they did have direct experience with God’s presence? Could that count as legitimate evidence of God?

King believed that it could. In a seminary class during his second year at Crozer, he wrote a paper titled “The Place of Reason and Experience in Finding God,” in which he argued that experience of God constituted legitimate evidence for God’s existence. Direct experience with God did not have to include hearing God’s audible voice – though for some African American Christians, it clearly did. “Religious experience is not an intellectual formulation about God, it is a lasting acquaintance with God,” King wrote in his seminary class paper. “So it is quite obvious that religious experience ranges from an every day experience with reality to the very height of mystic ecstasy.” And all of that, he argued, could serve as legitimate reason to believe in God.

In his seminary paper, King cited the turn-of-the-century Harvard psychologist William James for the argument that religious experience could be a legitimate way to find God and know that God exists, but in his sermon in Montgomery, he credited the idea to an older source: the enslaved people on southern cotton plantations who found God through a direct encounter. They were “the greatest psychologists that America’d ever known” because of their recognition that faith in the promise that their suffering would not last forever gave them the strength to go on.

So, in his Christian apologetic, King did not feel the need to prove God’s existence from abstract principles or provide historical arguments for the Bible’s veracity in order to argue for the existence of the Christian God. Instead, he pointed out that without a personal God of justice and love, there would be no hope in the struggle and no “meaning and purpose” in life. And then he could point to the evidence of personal experience to show that the God that people hoped for and longed for really did exist. He could remind the people in his congregation that in the moment when things looked most hopeless, faith in God was more necessary than ever. If the struggle seemed difficult even with God’s presence, it would be impossible without God – because there would be no meaning in the struggle at all and no guarantee of a better day.

King’s sermon worked. After his message, African Americans maintained their bus boycott for another three months. By Christmas that year, they could celebrate the end of segregation on Montgomery’s buses and the end of one phase of their long struggle for civil rights.

The arguments for faith in God that King presented in Montgomery continued to guide him for the rest of his life. In his last public address, delivered in Memphis the day before he was assassinated, he employed biblical imagery of the “promised land” to speak of his confidence that victory over injustice would be achieved, even if he would not live to see it. It was his faith in God’s justice that gave him an unshakeable hope that the cause of right would prevail in the end, no matter how difficult things looked.

But King’s arguments for God were very different from those of most white Christian apologists – especially the arguments of Christian evidentialists. The main reason for that, I suspect, is that traditional evidentialist apologetics attempts to find clues to an absent God from history and science. For people who have never sensed God, white Christian evidentialist apologists have pointed to evidence from the complexity of the universe to argue that the cosmos must have had a designer and they have appealed to evidence from historical testimony to argue that the gospels present an accurate record of Jesus’s life and resurrection. It is an apologetic based entirely on an academic study of evidence rather than an examination of personal experience or psychological need. But that form of evidentialism has been almost entirely unknown in the historic Black church.

Instead, African American Christian apologetics, including the sort that Martin Luther King appealed to, was premised on the idea that God is not absent and that people do not have to look to history or to the creation of the universe to find clues to God’s existence. Instead, they can find evidence for God from their own experience with God in the present and from their deepest longings. If injustice seems to be prevailing at the moment, it is a reminder that people need to look more deeply to find evidence of God at work even in the present – because it is in the darkest moments of injustice that the promises of God’s justice and the ultimate triumph of the right can appear more real than ever.

I’m not sure that this form of apologetic would seem persuasive to people who have not experienced deep longings for justice and who have not walked the hot streets of a segregated city in order as a protest for human dignity. There’s a reason that King’s apologetic arguments were not taught at the time in white Christian college classes on evidences for Christianity.

But for those who were participants in the struggle, King’s evocation of the longing for transcendent justice and his reminder of people’s personal experience with God formed a persuasive argument for faith.