Tumultuous times of transition in the academic, evangelical, political, and social spheres have brought evangelical historians to an interesting midpoint of the summer. These conditions potentially foster fears that plausibly lead to the opportunity of faith.

This past spring, a number of colleges and universities announced their closing, notable from the Christian sector included the announcement from King’s College in Manhattan. Then more news of transitions came from Manhattan in May, with the passing of Timothy Keller, heir of the neo-evangelicals, a sire to the Reformed-Resurgence movement, and co-founder of TGC. SCOTUS delivered two key decisions related to education in late June, including rejecting Biden’s plan of student loan forgiveness and effectively ending affirmative action. Meanwhile, we’re all trying to figure out where to process these transitions, for Elon Musk continues to blunder his way through owning Twitter, by creating too much friction for users. A mass exodus to alternate social platforms—such as Mastodon, Bluesky, and Post—has perhaps found its terminus with Meta’s launch of the Threads application, which reported to have 100 million users within days of its launch.

These sudden cultural turns do not happen in a vacuum. Individuals are affected by them, while they manage their own adversity. Sometimes we conceal private adversity for the sake of everyone else, who seem overly burdened with managing the affairs of these meta cultural shifts. I’d say that’s the case for me. Too long have I played the role of the public intellectual, always ready to respond to and speak into the issues of cultural adversity, while quietly carrying the burdens of personal adversity. Nonetheless, doing so has been to the detriment of cultivating the opportunity of faith by conveying how I’ve faced my fears.

I began to ponder this following a major transition that occurred in our family life. This last week, we laid to rest our beloved Maltese, Lenny. Fortunately, we were blessed that he had quite the long life of sixteen years. Our decision to transition him came after two long years of observing his decline. The affects of blindness, deafness, immobility, and incontinence—along with increasing signs that he was in real pain and discomfort—caused us to share with our children that it was time. Since our oldest is fourteen, essentially, none of our children know a world without Lenny. This past week has been a time of deep grief for all of us, grief we didn’t think would be there.

But that’s not all. The decline of Lenny has occurred concomitant to the decline of my father. Nearly two years ago, my father went missing, after leaving home to get a haircut, go to Home Depot, and then pick up some pool chemicals from Leslie Pools. After nearly twenty-four hours, he was found three hours from home in Northeast, Texas, near the Texarkana border. It was at that time that my mother and he decided to get a definitive diagnosis of dementia. Granted, we all suspected this condition when he was in his late fifties, and we kept finding post-it note reminders all over his home office. However, over the last couple decades, the situation shifted from seemingly innocuous absent-mindedness that made good fodder for jokes and jests about dad’s “memory” to real endangerment and risk to his safety in his late seventies.

Why have I quietly concealed this burden? Imagine being a historian on the hunt for a tenure-track position in your early forties, while personally wondering whether the condition of your father lies dormant within you. I mean, our profession relies on the use of memory.

I’ve always prided myself in having a stellar one. I’ve credited it to certain habits. Voracious reading, storytelling, and writing are among those habits. As an elementary aged child, I told such good stories to my teachers that they pushed me to compete in UIL as a storyteller. That was the start to discovering my love and skill for teaching. I’ve never been a notetaker. Left-handedness never lent itself to fostering penmanship, so my notetaking has always been sporadic. Perhaps that’s what caused me to skillfully map webs of information in my mind to reinforce oral and reading comprehension. While my penmanship is atrocious, I’ve been fortunate to benefit from the keyboarding power of the digital age, in order to compensate for my poor penmanship and facilitate a love of composition.

Nonetheless, facing the fear of memory loss has reinforced new habits. I make meticulous visual presentations for my lectures because they provide a handy tool for reviewing the lecture material during the hour or minutes prior to a lecture. I have developed an extensive digital archive of primary and secondary sources. I leverage social media as a record of my reading. I can refer back to it to recall important quotes, their sources, and when and where I read them.

The fear of memory loss has also created a sense of urgency, which is counter-intuitive for me. Because my personal disposition is that of a risk-taker, I attempt to counteract the propensity to carelessness that commonly accompanies risk-taking with patience and prudence. I let my study and research bake until I feel certain it is time to unveil my interpretations and conclusions. I also attempt to be clear when my ideas are experimental. In fact, I employ social media to publicly workshop and experiment with ideas and interpretations of history. The process of being a slow professor or intellectual has proven immensely beneficial, as I commonly uncover more archival data that complexifies and thickens the texture of my research, which sometimes moves it into a new trajectory.

Fundamentally, the fear of memory loss has caused me to be a more vigilant and curious historian, who values both the breadth of general macro-histories and the depth of detailed micro-histories. I cannot settle to be merely an intellectual historian because I know the bearing that social and cultural contexts have on an intellectual’s development, nor can I settle for merely mastering the discipline of history, for I know that having a depth of understanding in other disciplines augments my mastery of the historical discipline.

Lately, I’ve been revisiting historical methodology and practice, specifically in reference to the project of Christian history. The summer is optimal for carving out balcony time to re-assess and re-evaluate how I’ve been doing as a “Christian historian” who works with the history of Christianity in its modern context. It’s not just student evaluations that stimulated this interest. My work with the Conference on Faith and History burdens me with this introspective responsibility, as well as current issues in our discipline.

The publication of Myth America (Basic Books, 2023), edited by Kevin Kruse and Julian Zelizer, has stoked the fires, once again, of tensions between ideological histories from the right and ideological histories from the left. Johann Neem’s review of the book at The Hedgehog Review represents these tensions. I found the review curious because Neem appeared offended that Kruse and Zelizer did not write the book he wanted them to write, one that legitimated his ideological commitments as well as theirs.

This review caused me to step back and revisit how everyday AHA historians probably perceive CFH and a historian like me, at a place like Wheaton College. Over the past couple years at CFH, I have striven to facilitate fellowship between believing historians, while fostering welfare between our niche guild and the wider guild of historians. I’ve also tried to figure out how to be a Christian teaching history from a Christian informed framework, while also maintaining the values of a liberal and pluralistic society.

Hence, over the past couple days I’ve been re-reading Marsden’s The Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship (OUP, 1997), revisiting select chapters from History and the Christian Historian (Eerdmans, 1998) and Religious Advocacy and American History (Eerdmans, 1999), and I’ve dipped into Kathleen Wellman’s Hijacking History (OUP, 2021). The process of doing so has been enlightening. It seems the problems I’m concerned about have been the perennial problems of evangelical historians since the conception of the neo-evangelical movement and the attempt to place it in a longer history of evangelicalism.

I’ve drawn two conclusions that lead to two suggested proposals. First, we live in an era where we have to manage ideological tensions rather than resolve them. Second, a context of uncertainty is the opportunity to be faithful in the face of our fears.

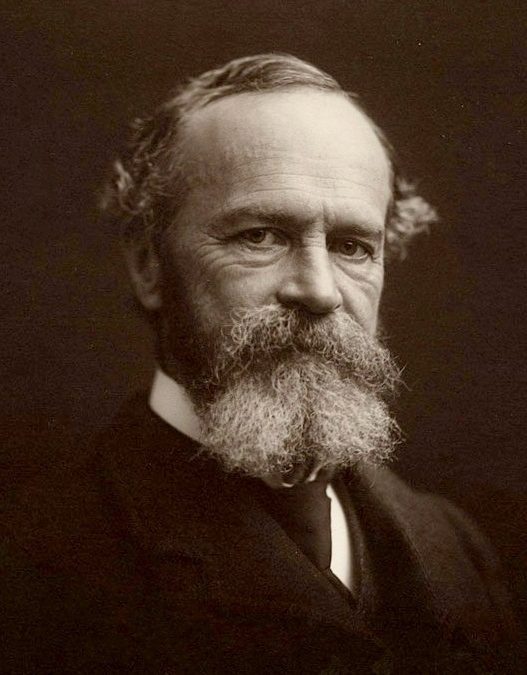

To illustrate these conclusions and proposals, I’d like to use anecdotes inspired by my research on William James, the founder of the American school of psychology, co-founder of the philosophical school of pragmatism, and professor at Harvard University from 1872–1910.

If Christ Came to Chicago and Pragmatic Liberal Pluralism

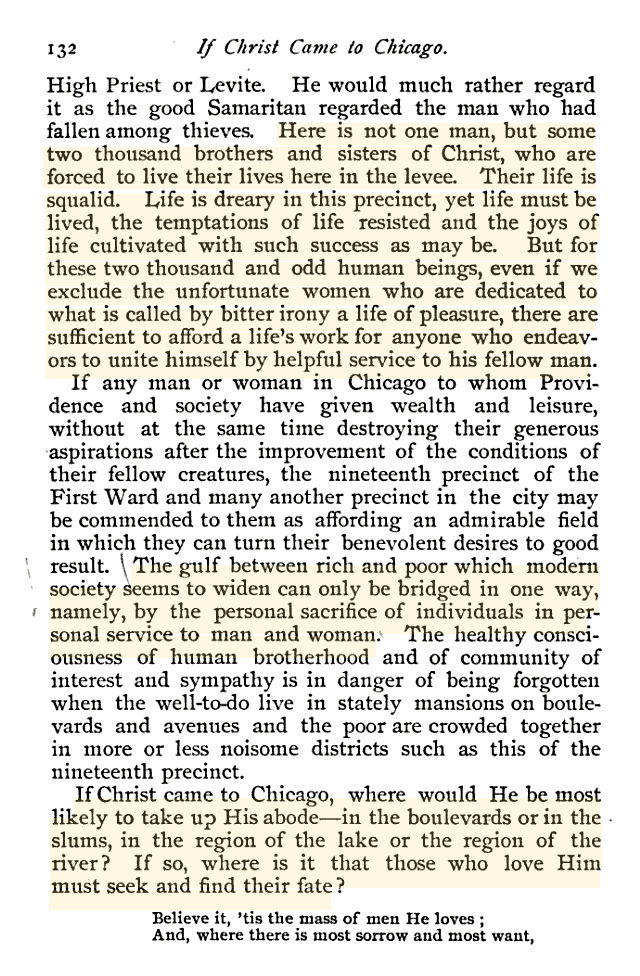

Recently, I shared the following quote from W. T. Stead’s, If Christ Came to Chicago (Laird and Lee, 1894), on social media:

“The gulf between the rich and poor which modern society seems to widen can only be bridged in one way, namely, by the personal sacrifice of individuals in personal service to man and woman” (132).

My CFH colleague, Elesha Coffman, rightly commented on Facebook:

“That’s a really silly statement, yet one that a lot of people would rather believe than the reality that massive, systemic problems require massive, systemic solutions.”

Much could be said about this, so I’ll try to be concise. First, Elesha’s critical engagement is absolutely sound. Out of context this notion is simplistic and absolutizing in a problematic manner. There are alternate proposals that should be entertained, and Elesha offers one such suggestion.

I originally shared the quote because I was bookmarking it for research. I bookmarked it not simply because I thought it was an important idea but because William James thought it was an important idea. You see, the copy I am reading of W. T. Stead’s If Christ Came to Chicago was William James’s personal copy, marked up by him. I’ve enjoyed reading this copy because I can see James’s marginalia and reflect on what he thought was important about Stead’s reporting.

Second, both the quote and Elesha’s response represent ideological commitments that are commonly set against one another and characterize what most would assume are ideological commitments from the right and from the left, respectively. Most fascinating is that when you put the quote in its context, you will see that Stead is teasing out how individual action can lead to systemic changes. The quote comes from the conclusion of his chapter on the 19th precinct of Chicago and follows his comparison of social conditions in Chicago near the river to social conditions near the lake. He reproaches the rich, who live by the lake, for not being concerned about the needs of the poor, who live by the river.

Stead begins the next chapter by commending individual saloon keepers, who subsidized free lunches to vagrants from liquor profits in their saloons. Approximately 60,000 citizens were fed lunch daily by the 3,000 saloon keepers in Chicago. Before you could shoe the shoeless with a pair of Tom’s in the early 2000s, you could feed the out of work by purchasing a dram of whisky in the late 1890s. The charity of these individual saloon keepers complicates our perception of the temperance movement. The temperance movement’s systemic agenda to address intemperance in society with the public policy of prohibition eventually would amplify hunger because the public policy would thwart the ingenious efforts of individual saloon keepers to alleviate the hunger of their clientele.

You see, there is always a trade-off when you attempt to negotiate between free-market capitalism and social-democracy. Both systems offer solutions. One has to manage the tension and determine which solution is pragmatic.

Sadly, uncertain times problematize which solution to pursue. We live in an era where a two-party system is increasingly polarized and so are the economic policies that follow those systems. Thus, if we are to maintain a liberal and pluralistic society, we have to be able to manage tensions and live faithfully in the midst of various options and solutions that may be simultaneously employed to resolve these tensions. We need systemic and individual action working in cooperation.

Marsden’s Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship reminded me of this principle, and he did so by retrieving William James:

William James, in his famous essay “What Pragmatism Means,” provides a helpful image of how a liberal pluralistic society ought to work. James describes pragmatic liberal discourse as ‘like a corridor in a hotel. Innumerable chambers open out of it. In one you may find a man writing an atheistic volume; in the next someone on his knees praying for faith and strength; in the third a chemist investigating a body’s properties. In a fourth a system of idealistic metaphysics is being excogitated; in a fifth the impossibility of metaphysics is being shown. But they all own the corridor, and all must pass through it if they want a practicable way of getting into or out of their respective rooms.’ I find this image quite congenial. Essentially my position is that in a pluralistic society we have little choice but to accept pragmatic standards in public life. (Kindle loc. 561–66)

In other words, various solutions may work to assuage or resolve the tension. Selecting the one that you think works best for you is your responsibility, and a liberal society offers the freedom for various people and groups to procure their solutions. Additionally, it is your responsibility to respect the alternate methods and decisions of others because we all share the same space.

Experimental Pedagogy and Facing Fears with Faith

This fall I will teach “American History to 1865.” I’ve elected to adopt Thomas Kidd’s American History, Volume 1 and juxtapose it to Volume 1 of YAWP. It’s an experiment inspired by Lendol Calder’s essay “Uncoverage: Towards a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey” (The Journal of American History [March 2006]:1358–70).

This past spring I followed Calder’s technique for my “American History from 1865” course, using Howard Zinn’s and Paul Johnson’s histories as my texts. In my student evaluations, one student excoriated me for using inferior texts and focusing my pedagogy on a German inspired seminar style rather than filling students with awe from brilliant lectures. The student’s evaluation implied that I designed the course to camouflage my inadequacy to teach the course.

Reading that evaluation was a rough experience but an opportunity to extend a liberal and pluralistic mindset with someone whom I share space. I had to remind myself that this student’s expectations and desires were different from mine, and I needed to accept and recognize that student’s liberty to express those views.

Nonetheless, this student evaluation shook my confidence about my plan for the fall. Again, William James has been helpful.

From 1876–78, James experienced a number of transitions. He met and married Alice Gibbens, and she became the compass to direct his emotional, social, and intellectual energy. He became stubbornly committed to Harvard University, despite John Hopkins attempts to court him and Harvard extending to him only part-time contracts for his work (Richardson, William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism, 212–15).

During this time, he drafted the essay “Rationality, Activity and Faith” which was published a few years later in The Princeton Review 58 (July–September, 1882): 58–86. This essay offers summaries of protean ideas that he had been developing into his notions of consciousness, pragmatism, and positive psychology. These notions would reach their maturity in his publications: Principles of Psychology (New York, 1890), The Will to Believe (New York, 1897), The Varieties of Religious Experience (New York, 1902), and Pragmatism (New York, 1907).

I found his definition of faith in this essay reassuring:

Now there is one element of our active nature which the Christian religion has emphatically recognized, but which philosophers as a rule have with great insincerity tried to huddle out of sight in their pretension to found systems of absolute certainty. I mean the element of Faith. Faith means belief in something concerning which doubt is still theoretically possible; and as the test of belief is willingness to act, one may say that faith is the readiness to act in a cause the prosperous issue of which is not certified to us in advance. It is in fact the same moral quality which we call courage in practical affairs…the power to trust, to risk a little beyond the literal evidence, is an essential function. (70, 71)

James goes on to illustrate the act of faith by recounting the dilemma of a climber who comes to a chasm that he must leap across. James described the climber’s faith as one which results in two plausible conclusions. First, the climber’s faith may inspire him to muster a confident courage to achieve what otherwise might have been impossible. Second, his faith might be grounded in fear and despair, which causes him to plumet into the abyss. He draws this conclusion about faith:

In this case, and it is one of an immense class, the part of wisdom is clearly to believe what one desires, for the belief is one of the indispensable preliminary conditions of the realization of its object. There are then cases where faith creates its own verification. Believe, and you shall be right, for you shall save yourself. Doubt, and you shall again be right, for you shall perish. The only difference is that to believe is greatly to your advantage. (75)

In the end, we have to face our fears in a way that cultivates faith rather than despair. Whether our fear is death, memory loss, job security, institutional death, unsettling turns in public policy, or the end of modernism, democracy, and evangelicalism (see Jake Meador’s Mere Orthodoxy piece)—faith must manifest as an opportunity and possibility rather than doubt and despair.