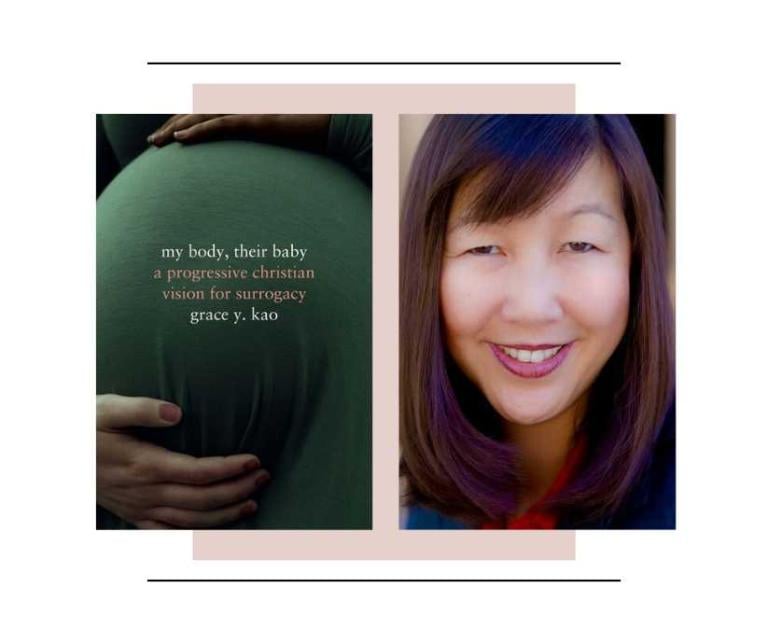

While assisted reproductive technology has made it possible for many people to welcome children into their families, these technologies and the associated practice of surrogacy have been controversial. Grace Y. Kao, Professor of Ethics and Sano Chair in Pacific and Asian American theology at Claremont School of Theology and herself a surrogate mother, explores these complex issues in her new book, My Body, Their Baby: A Progressive Christian Vision for Surrogacy, published this month by Stanford University Press. As Kao persuasively and provocatively argues in her book, “collaborative reproduction can be an ethically justified way of bringing children into the world if the members of any arrangement proceed justly with care.” Her goal in writing the book is to provide “a positive vision where surrogacy could be a thing of beauty and advance certain commitments progressive Christians already profess as holding.”

I had the good fortune of learning about the history of surrogacy, the diverse Christian viewpoints on the practice, and the arguments of the book during a conversation with Kao this month. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Melissa Borja: Let’s get the story behind this book. What motivated you to write it? Tell us a little bit about the story behind its development.

Grace Kao: I am an ethicist. I do have interests in bioethics, but I’m not a bioethicist per se. When you teach feminist ethics like I do, that involves reproductive issues, and I have academic and personal interests in that area.

But that is not what led me to write the book. What led me to write the book was simply that, here I was, living my life very visibly pregnant, and all sorts of people were like, Whoa, what is this third pregnancy? Because my kids at that point were six and eight [years old]. Yes, I was pregnant, but it wasn’t mine–it was my friends’. And then that would lead into conversations, and [people] would ask me about our whole set-up…So it was the encouragement from friends and also my coming to see through these exchanges that people were really interested in this topic because they didn’t know a lot about it. They also had very strong misperceptions about surrogacy, so then it became a personal mission for me to set the record straight.

MB: I was intrigued by the misperceptions that people have about surrogacy and the range of theological positions on the issue. But before we get into the weeds of those issues, please outline the main arguments of your book.

GK: I’m trying to say surrogacy can be a morally acceptable or justifiable way of bringing a child into the world. In fact, it could even be a beautiful thing. And I’m also trying to say that if you hold feminist or progressive Christian commitments, you don’t have to abandon them in order to say “thumbs up” on surrogacy. Now, having said that, I think a lot ethically hinges on the details of the arrangements, and so I offer principles or norms to guide the formation of surrogacy relationships.

MB: The history of surrogacy is pretty interesting, and surrogacy is not a new invention. In order for us to understand where we are today, give us a little bit of background on the history of surrogacy and how it’s changed over time, especially in relation to technology change, social change, and political change.

GK: We’ve got biblical stories about surrogacy. You’ve got Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, and Ishmael right in Genesis. We also have Jacob and his sister wives, Leah and Rachel, and how they “offer” their maidservants to him to have children by proxy. And then you have Ruth. She’s not commonly read as a surrogate, but she can be read as a surrogate because it’s her mother-in-law (Naomi) who arranges the whole thing, Naomi is described as nursing the child Ruth bore, and the townspeople celebrate the child as the mother-in-law’s child, not Ruth’s. And in a footnote, I talk about the fact that there’s been this discovery of Nuzi tablets that talk about the Hurrian people, who also had “children by proxy” practices. The Code of Hammurabi also talks about how if a wife were infertile, she could prevent her husband wedding another wife by “offering” him a maidservant for the purpose of producing children. So, as you know as a historian, we don’t know if the Code really functioned as law, but clearly surrogacy is in the ether among ancient peoples.

The biggest jump historically is the introduction of IVF [in vitro fertilization]. With traditional surrogacy, the intended father basically had to have sexual intercourse. In some cases persons could do artificial insemination. But the model before IVF was traditional surrogacy, and the earliest contracts we have in the U.S. are from the 1970s and were all traditional surrogacy contracts. But in 1978, the first baby conceived by IVF was born—Louise Joy Brown. And so now gestational surrogacy became technically possible. If you can produce an embryo outside of a pregnant-capable person’s body, then technically you might be able to transfer [it into the body of another], and that ended up happening first in the mid-1980s.

Also in the mid 1980s, we had terrible surrogacy disaster stories involving traditional surrogacy. You had the “Baby M” saga, a New Jersey case, and then across the Atlantic in England, we had the “Baby Cotton” case. So, the combination of the rise of IVF making gestational surrogacy possible and the disasters that happen with traditional surrogacy changed the landscape. Now, most experts think 90-95% of all surrogacy arrangements are gestational, wherein the carrier has no biogenetic relationship to the child.

You ask about politics as well. There are ample surrogacy laws. Every state has a different law. Every country has a different law. And what you see is, whatever the policies are in one place, if they are “too restrictive” or if the total package is too expensive, people within that jurisdiction will leave if they can afford to do so, to receive cross-border care in other places. You probably have heard of this term reproductive tourists, and I make an argument that sometimes we’re talking about reproductive exiles, people who would prefer to get their reproductive needs taken care of at home but are perhaps legally prohibited from doing so, so they will travel.

MB: I wonder if there are social developments that have shaped attitudes about surrogacy as well as its practice.

GK: I would say this model of the so-called traditional family—mother and father raising their biogenetic children in a home—has clearly been expanded by single parents, blended families, and same-sex headed families, so there’s a sense in which the traditional family, as we know it, is no longer the dominant family type. And there’s been a growing social awareness and social acceptance of same-sex headed families, particularly two gay men. In many cases, there are all sorts of reasons why gay men, if they can, choose surrogacy over adoption. So that’s the social part. Take, for instance, the state of Israel. Israel’s really interesting. Israel’s pro-natalist. Israel gives tons of financial and social support for IVF and surrogacy. They used to prohibit it for gay men. The highest court in the land actually said that it’s discriminatory for us to block gay men from accessing these services, and so now gay men can do so. Prior to that, they would go outside if they wanted to pass on their genetic lineage.

MB: Your response to the social aspects of the recent history of surrogacy hinged on this idea of a traditional family. I think that opens the next terrain of conversation that I’m interested in exploring, which is ideas about surrogacy from the vantage point of different Christian groups. And, if I’m understanding this correctly, Christian ideas about surrogacy are tied up in ideas of what a traditional family should be like and what traditional sexual norms should be like. You’re entering into this conversation as someone who has served as a surrogate, but also as a Christian ethicist who is trained as a researcher. Tell us about the specific interventions you, as a Christian ethicist, want to make in this big debate about surrogacy. How do you want your book to change how Christians think and talk about surrogacy?

GK: I actually want to make many, many interventions, and I will talk about the big ones and then the small ones. So, in terms of the progressive Christian values that I hold, I want to say if you truly affirm marriage equality—and many mainline Protestant denominations do, as do progressive Catholics—and you also affirm the traditional idea that children are a good of marriage, not a requirement (because I also believe parenthood is a vocation to which not everyone is called), then there needs to be a pathway for two men to become parents. And unless you’re going to hold the position that their pathway is adoption and everyone else’s pathway is natural birth, then I think surrogacy is the next step, especially since a lot of these progressive or mainline Protestant denominations have also officially affirmed the conscientious use of IVF for infertile, married, heterosexual couples. There’s a way in which you can read—although medically not so, but socially—two men in a marriage as an infertile couple, socially infertile. So if these churches have said “thumbs up” for IVF, then what you need in the same-sex case is IVF plus a surrogate. It doesn’t have to be a gestational surrogate; it could be a traditional one. I talk a little bit in the book about that.

The biggest thing I want to reexamine is this commonplace notion that adoption is the morally superior alternative to any use of assisted reproductive technology. I want people to think more seriously about that because adoption has its own challenges. I’m not pooh-poohing it, but it has its own challenges, its own difficulties. I explain in the book many reasons why I don’t think the supposed advantages of adoption over the use of ART are so obvious. And I also think it’s really unfair that we–the broader society–place the responsibility of caring for needy children—children who might be homeless, orphans, children who might be eligible for adoption—on the infertile. Look, I have two naturally conceived children. No one questioned my desire to have biogenetic children. Why are persons who don’t just “accept” their infertility but are actively attempting to overcome it through use of ART, including surrogacy, frequently being put in the position where they must justify their yearnings and desires?

What I don’t talk about in the book, but what I think is very interesting, is the difference I’ve encountered between evangelicals and Catholics. Catholics in conformity with the Magisterium, at the end of the day, are actually very consistent. They are anti-artificial contraception. They are anti-abortion. For them, life begins at conception. Now a large number of evangelicals, if you press them, will say they, too, believe that life begins at conception. This is why they consider abortion immoral. But a surprising number of evangelicals are okay with IVF. They are okay with it because, they think to themselves, someone needs help having children. But if you know anything about IVF, you know you’re likely going to create a number of embryos that are not going to get transferred or that will die in the process.

I’ve met so many people while carrying my friends’ baby—evangelicals—who were like, What a beautiful thing, this is fantastic! But who are also anti-abortion. And I’ve always wondered, is it because you just don’t know enough about IVF, or you think abortion is different because it’s a fetus versus an embryo? This is the so-called scandal of IVF from the perspective of the Catholic Church. And sure, if you think that a one-day embryo has the same moral status as a grown human being, you should be scandalized by IVF. So I want to make those types of interventions.

MB: Actually, I did want to ask specifically about the different parts of the Christian church and how they engage this issue. I was really intrigued by evangelicals’ position on surrogacy. The Catholic position I was familiar with, but I wasn’t quite sure where evangelicals fell on this issue, and you have encountered evangelicals who are pretty excited about IVF. Even though it’s very clear that it’s rooted in progressive Christian perspectives, do you see this book as trying to speak to evangelical Christians and helping them think about this issue in a new way?

GK: As you know, evangelicalism is going through its own growing pains about sexuality. There’s the evangelical left, like the Sojourners type of folks, and there’s the evangelical right. Left-leaning evangelicals are thumbs up about same-sex marriages—two women or two men—then, hey, are you saying adoption is the way they will affirm one of the traditional goods of marriage, as per Augustine? That to me comes too close to, Oh, you’re gay, well, God has called you to be celibate. You know what I mean? Like, Oh, you’re in a same-sex marriage, okay, adoption is the path for you. The other thing I should say is that we’re playing now with conservative versus traditional. I think surrogacy is both traditional and contemporary. It’s traditional because most of the time, people want it. Why? Because they want biogenetically-related children. And [you see that] if you look at the way people select gamete donors or the way they are trying to have genetic replacements of the so-called infertile parent. Let’s say you have two gay men. Let’s say one is Asian, one is white. They are trying to create embryos that might physically resemble both of them. If you have a man and a woman, they, too, are doing very similar things. That’s a very traditional thing, the idea that a family is biologically and morphologically resembles one another.

MB: You write and think about a lot of different things. This is why I always enjoy being in conversation with you—you are always engaging in lots of different topics and questions. I’m curious: what are you working on next?

GK: I have a contract to do a volume introducing Asian American Christian ethics. I co-edited an anthology published in 2015 where I helped to bring this project together. But the next thing to do is that one volume because the field has changed.

I’ve been wanting to really flesh out an Asian American theology of reparations, and I have four case studies involving Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Filipino Americans and Asian American churches in Hawaii in relation to native Hawaiians. But in order to do it well, I have to know all of the details. I need to do interviews, and these are not necessarily methods I’m trained in. So that is probably my next big project.