Today is December 23: the last day to get overnight delivery for presents to arrive in time for stuffing Christmas stockings, the last full work day before Christmas, and, most important, the day to celebrate what is arguably the most beloved fictional holiday—Festivus.

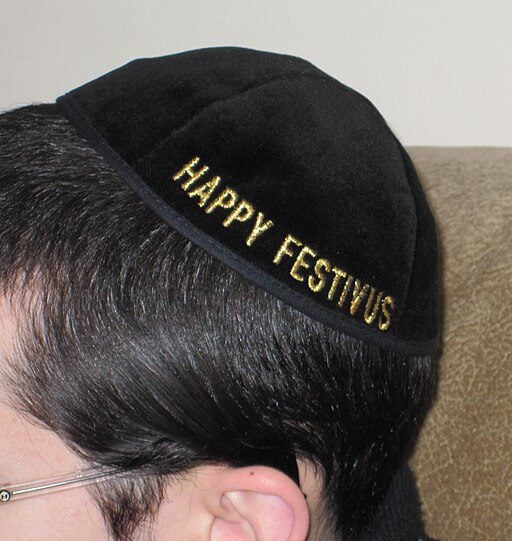

For the unacquainted, Festivus is a holiday that entered mainstream culture through the television show Seinfeld. It is something of an anti-Christmas, featuring some of the basic elements of any holiday, like family gatherings and feasting, while also embracing distinctive rituals: public feats of strength, displays of an unadorned aluminum pole, and an airing of grievances, when celebrants declare how family members have disappointed them in the past year.

Both onscreen and in real life, the holiday is an invention. Festivus is the creation of Daniel O’Keefe, the father of one of Seinfeld’s writers and producers, Dan O’Keefe, who later wrote the holiday into the episode “The Strike,” which aired in December 1997. On the show, Festivus is the invention of Frank Costanza, the father of George Constanza, who conceived of the holiday as an alternative to Christmas, which he rejected for being too commercial. But like many invented holidays that derive from film and television—May Fourth, The Perfect Date, Galentine’s Day—Festivus and its rituals have become a regular part of the December calendar for many people.

The enduring appeal of Festivus reveals much about Americans: the influence of popular culture on our lives, the mixed emotions that Christmas elicits, the fact that many of us are disappointed by our relatives. The elements of Festivus—family, feasting, and feats of strength, to name a few—have timeless appeal.

But the Seinfeld iteration of Festivus, which is the version that has taken hold in American popular culture, is also very much a product of its time. Although Festivus celebrations have evolved and taken on a life of their own in the past three decades, I was curious about the “original” version of Festivus that took this holiday mainstream. While rewatching the original Seinfeld episode that featured Festivus in December 1997, I was struck not by how people observe the holiday and practice its rituals, but how the different characters—Mr. Kruger, the executive; Kramer, the eccentric neighbor; and, of course, George and Frank Costanza—talk about Festivus and navigate the workplace politics around it. Specifically, for the characters on Seinfeld, Festivus is a holiday that is a “heritage” event that merits rights, respect, and recognition. To be sure, the characters have different feelings about Festivus and often self-serving interests in ensuring that the holiday is recognized as legitimate. But as a scholar of religious pluralism, I saw in “The Strike” and its representation of Festivus a reflection of how Americans in the 1990s were grappling with religious diversity. On Seinfeld, the story of Festivus is a story about life in a multireligious society and the complications of accommodating religious difference.

Religious diversity and the challenge of putting pluralist ideals into practice was a regular topic of discussion in the 1990s. By this point, midcentury immigration reforms (in particular, the 1965 Hart-Celler Act) had transformed the racial and religious demographics of the United States. More Americans than ever before identified as Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist—a significant change for a country with a long history of Christian predominance. At the same time, the ideology of religious pluralism, which promoted harmonious relations across religious difference, was changing American culture and reshaping how people related to neighbors with different identities, beliefs, and practices. Finally, questions about religious diversity and religious freedom were at the heart of major legal and political developments during this decade. Most notably, after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Employment Division of Oregon v. Smith in 1990, a broad coalition of religious groups ranging from Baptists, Jews, Quakers, and Unitarians organized in defense of religious freedom, which they saw as under threat. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act, passed by Congress in 1993, was the result of this new politics of religious freedom.

It is against this backdrop that Seinfeld introduced America to Festivus, imagined as an alternative to Christmas for those disillusioned by its consumerism. Frank Costanza explains to Kramer that he developed the idea for a different celebration after he fought with another man over the purchase of a toy for his son, George. “I realized there had to be another way!” he recalls. The result of this epiphany was a new holiday altogether: “A Festivus for the rest of us!”

Frank celebrates Festivus enthusiastically and draws on notions of identity as he urges his son to embrace the holiday, too. “George, Festivus is your heritage—it is part of who you are,” Frank declares one day as he brings the Festivus aluminum pole into the local coffee shop. George groans. “That’s why I hate it,” he laments as he puts his face in his hands.

George is in fact quite embarrassed by the tradition. After his father plays a cassette tape recording of a previous Festivus celebration, George storms out of the coffee shop, screaming, “I hate Festivus!” At another point in the episode, when Jerry explains the holiday to Elaine, George loses his patience. “I can’t take it anymore,” he yells as he storms out of the coffee shop. “I’m going to work!”

As is often case with holidays and situations where people have different beliefs and practices, work is where the situation gets more interesting. Kramer, recently rehired at H & H Bagels after a lengthy strike over wages, is intrigued by Frank’s description of the holiday. He requests that his boss allow him to take time off on December 23 so he can celebrate Festivus. His boss objects, pointing out the specific circumstances under which he had hired Kramer to work. “I hired you to work during the holidays,” the boss says. “This is the holidays!”

Angered, Kramer reaches for an argument that was very familiar to Americans in the 1990s: rights and religious freedom. “You know you’re infringing on my right to celebrate the holidays!” Kramer responds. His boss objects—“That’s not a right!” he says—which prompts Kramer to throw off his apron and declare, “It’s a walkout!” Later in the episode, Kramer is shown protesting the bagel shop, yelling “No bagel, no bagel!” and carrying a picket sign that reads “FESTIVUS YES! BAGELS NO!”

Despite his reluctance to celebrate the holiday, George, too, unexpectedly finds himself making religious freedom arguments about Festivus at work. When George is confronted by Mr. Kruger, his boss, about his fake Christmas gift—a donation to the Human Fund, a charity that George invented—George finds a way out of trouble by turning to the family holiday he despises. “I gave out the fake card because the truth is, I don’t really celebrate Christmas,” George explains. “I celebrate Festivus.” He later elaborates with emotional details about the minority status of his family’s identity, beliefs, and practices. “I was afraid that I would be persecuted for my beliefs,” George says. “They drove my family out of Bayside, sir!”

To offer proof that his family celebrates the holiday, George brings Mr. Kruger to the Costanza home for the Festivus dinner, which he describes as “embracing my roots.” For his part, Mr. Kruger behaves exactly as an open-minded and religiously tolerant boss was expected to behave in the 1990s: with careful words and measured curiosity. At one point, Frank shows off the undecorated aluminum pole to Mr. Kruger, who uses the language typical of modern Americans trying to make their way in a multireligious society. “I find your belief system fascinating,” Mr. Kruger says to Frank.

Mr. Kruger is generally portrayed on the show as being a rather dimwitted boss. (In fact, during the Festivus airing of grievances, Frank points at him and says, “My son tells me your company stinks!”) And so the fact that Mr. Kruger takes Festivus seriously as a legitimate religious holiday subtly invites the audience to consider some uncomfortable questions. Do Kramer and George have beliefs about the holiday that are, as the courts often ask, “sincerely held”? Should we take people at their word when they say that they celebrate a particular holiday and thus deserve rights and accommodation? Is Mr. Kruger (and perhaps America) being duped? In the show, as with religious freedom questions in real life, the answers are not easy or obvious. Alongside the laughs prompted by Seinfeld’s tightly written jokes, the audience, aware of the uses and potential abuses of religious freedom claims in American life, feels a bit of unease—a grievance, perhaps, that they might air.

More than a quarter century after Festivus first appeared on Seinfeld, grievance is a central feature of our politics, and in an age of both kaleidoscopic religious diversity and strident Christian nationalism, questions about how to handle religious differences at work, in our schools, and in public life remain relevant. Rewatching “The Strike” made me see the particular context in which Festivus entered our popular culture, at the same time it reminded me that we are not all that far removed from the 1990s.