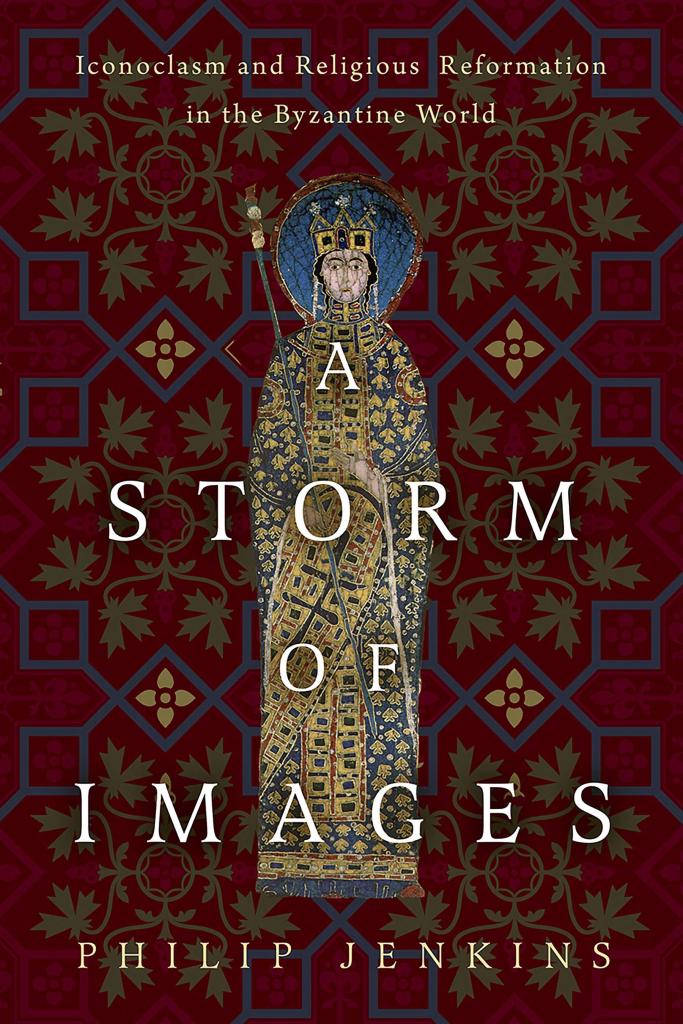

I am delighted to announce the publication of my new book, A Storm of Images: Iconoclasm and Religious Reformation in the Byzantine World (Baylor University Press)!

Here is the catalog description:

In the eighth century, the Byzantine Empire began a campaign to remove or suppress sacred images that depicted Christ, the Virgin, or other holy figures, whether in painting, mosaics, murals, or other media. In some cases, the campaign extended to breaking or wrecking images through what became known as iconoclasm. Over the following years, the emperors’ zealous movement involved other acts that closely foreshadowed the Reformation movement that would sweep Western Europe in the sixteenth century. Like that later Reformation, iconoclasm marked an authentic revolution in religious sensibility, with all that implied for theology, culture, and visual perceptions of holiness. This was a pivotal moment in the definition of Christianity and its relationship to the material creation. It was also a time of critical encounters with the other Abrahamic religions of Judaism and Islam.

With A Storm of Images, Philip Jenkins offers a compelling retelling of the saga of how the iconoclastic movement detonated ferocious controversy within the church and secular society as icon supporters challenged the image breakers. Decades of internal struggle followed, marked by rebellions and civil wars, purges and persecutions, plotting and coups d’etat. After their cause triumphed, the image supporters made the cult of icons ever more central to the faith of Orthodox Christianity. Iconoclasm marked a watershed in the history of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, and it contributed to Western attempts to establish new empires.

The questions raised during these struggles are all the more relevant at a time when such controversy rages over the public depictions of history and the removal of statues, monuments, and names associated with hated figures. As in those earlier times, debates over images serve as vehicles for authentic cultural revolutions.

You might think that this topic strays somewhat a bit from my earlier writings and research, but it actually fits very well into my earlier scholarly trajectory. Two of my most popular and best-received books were The Lost History of Christianity (2008) and Jesus Wars (2010). Each in its way dealt with the Christianity of the Eastern world in Late Antiquity, between about 400 and 900AD, so that in a sense, I am now completing an ambitious trilogy.

A number of common themes present themselves. One is Christology, the church’s repeated attempts to answer Jesus’s question “Who do they say I am?” (Mark 8.27). To speak of the image struggle in terms of icons seems to confine it to a distinctly eastern spiritual world far removed from “mainstream” Christianity, however we may define that term. In reality, the battle demonstrates clear continuities from the far better-known theological debates of the early Christian centuries and the Great Church. The Iconoclasm debates from the 720s onward followed directly from the Christological controversies that we associate with fifth-century councils such as Ephesus and Chalcedon, and the language of those older gatherings frequently surfaces in discussions of holy images. If we seek the conclusion of those famous Christological debates, we should not point to Chalcedon, in 451, but rather to the triumph of (pro-image) orthodoxy some four centuries later. Throughout, the image debate was centrally concerned with the fact of Incarnation.

The issues of the eighth-century crisis were ably summarized by the English lay theologian Charles Williams, who in 1939 described an incident in which imperial forces provoked a riot when they removed a great public image of Christ in Constantinople:

It was asserted that, by such an attack on representations of the Divine Flesh and Its Mother, the Emperor and his friends were denying the Incarnation; it was answered that because of the uniqueness of that Flesh representations were impermissible. “The image is the symbol of Christ,” said St. John Damascene; “the honor paid to the image passes to its prototype,” said St. Basil. “No image can depict the Two Natures,” answered their opponents; “every image is therefore heretical. His only proper representation is in the Eucharist which is He.”

My trilogy reflects another purpose that is also manifested in other writings of mine, namely to expand and de-center conventional Western and particularly American views of the development of Christianity. To oversimplify, even quite well-read Christians think of a Church history that begins in the Roman world, proceeds through medieval Western Europe, and then evolves into Protestantism at the Reformation, before leaping across the Atlantic. In reality, there is also a vast and age-old Christian history in the Orthodox world, and beyond that in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, which is the subject of the trilogy that I am discussing here.

In modern times too, all my work on Global/World Christianity has that same purpose of de-centering Western views, and expanding the vision to take full account of the worldwide realities of the faith. Among other things, this highlights the reality that for a great many believers through history, their experience is not that of a monolithic Christian state, but of living as subjects to other faiths, especially Islam. Very commonly, Christians have lived as oppressed minorities, or even majorities, with all that implies for the permissible range of religious expression and practice, not to mention the realities of persecution and martyrdom.

A Storm of Images continues and builds upon these long-standing goals of mine, and the themes that I present.

As to the strictly contemporary relevance of iconoclasm, I covered this in February in my Christian Century column entitled “Smashing Statues.” The story bore the subheading: “Iconoclasm isn’t just an expression of anger. It’s how we try to make new worlds.” As I remarked in that piece, John Calvin famously declared that “the human mind is a perpetual factory of idols.” I would adapt that to say that, time and again, history proves that the human mind is a powerful factory of image breaking, of iconoclasm.