Enduring violence has long been part of the Christian story—Stephen was stoned (Acts 7:54-60), Paul was beaten numerous times (Acts 21:30-31; 2 Cor. 11:25), and Peter was crucified upside down according to tradition (1 Clement, Letter to Corinthians 5; Tertullian, Prescription against Heretics 36). Indeed, the center of the Christian faith, Jesus Christ, endured horrible punishment and death on a cross, encouraging his followers to ‘take up their cross’ with him (John 16:24). And take up their crosses, they did. But how are we to think about this religious violence? How can we honor martyrs who followed Christ’s call to take up their cross (sometimes literally) without glorifying or overemphasizing violence, especially violence against the vulnerable?”

In the second century A.D., during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, an intense persecution against Christians broke out in Lyon, Gaul. A letter preserved in Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History records how some Christians were imprisoned for impiety and atheism (denying and thus dishonoring the Roman gods and goddesses). Despite the defense of a prominent young Christian Roman, the Christ followers were convicted of their crimes. The letter focuses on the valor of the accused, in contrast to a number who apostatized, as they undergo violence and death.

For those who are unfamiliar with martyr narratives from the early church, it is a common trope to depict the ‘heroes’ as a sort of gladiator or champion—those who reign victorious over their enemies. Yet, importantly, Christians rewrote these tropes to depict the enemy as spiritual, rather than physical. Further, the champions are not who you might think—in this instance, our hero is a woman with no physical or political power. Her name was Blandina.

Inverting Strength and Weakness

We are not given a ton of background information on Blandina in the text or otherwise. The letter mentions the concern of a fellow martyr, Blandina’s ‘mistress’, which implies that Blandina was a slave. We don’t know her age, although she might be a young teenager since she doesn’t appear to be married—this is pure speculation though. We do know that she was small and frail in body, which worried the other confessors, “lest the weakness of her body should render her unable even to make a bold confession” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, V.1.18). In sum, Blandina was a woman with no social status, no rights, and no physical strength to save her amidst torture and persecution—she is weakness personified.

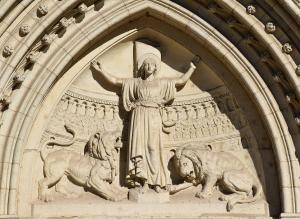

Yet, through Blandina’s weakness, “Christ showed that things which appear mean and unsightly and despicable in the eyes of men are accounted worthy of great glory in the sight of God, through love towards Him, a love which showed itself in power and did not boast in appearance” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History V.1.17). Despite her status and frailty, Blandina becomes the champion of the story in body and spirit. She “was filled with such power that those who by turns kept torturing her in every way from dawn till evening were worn out and exhausted,” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History V.1.18) and she encouraged her fellow Christians by saying “I am a Christian, and with us no evil finds a place.” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History V.1.19) Unfortunately, this does not deter her oppressors and she and the other Christians were subjected to all sorts of horrors, including branding, being fed to wild beasts, and crucifixion. Yet, the heroes of this story—our martyrs—hold fast against this torture, exemplifying bravery and faithful valor.

The Making of a Martyr: Bravery or Christlikeness?

I must admit, the account of this torture and martyrdom is truly sickening, with enough violence to fill a Quentin Tarantino movie. It can be hard to read! And I have a major concern in how this account is read and employed, indeed how all martyrdom accounts can be read: we might glorify the violence and their bravery, rather than the core of the narrative.

There is a temptation amongst modern readers to have a Braveheart mentality, where our hero fights for their principles and faces death bravely, screaming out ‘freedom’ along the way. What bravery, we might think. Indeed, there is some similarity between this famous movie scene and the declaration by Blandina, ‘I am a Christian’. In these instances, Blandina becomes the victorious gladiator in the colosseum, not by strength or skill, but by faith. But is martyrdom truly about Christian bravery?

What is important, here, is that bravery or the ability to withstand violence is not the point of the text at all. Rather, the focus is on Blandina’s conformity to Christ, mirroring him in life and death.

Now Blandina, suspended on a stake, was exposed as food to wild beasts which were let loose against her. Even to look on her, as she hung cross-wide in earnest prayer, wrought great eagerness in those who were contending, for in their conflict they beheld with their outward eyes in the form of their sister Him who was crucified for them, that He might persuade those who believe in Him that all who suffer for the glory of Christ have unbroken fellowship with the living God… she the small, the weak, the despised, who had put on Christ the great and invincible Champion, and who in many rounds vanquished the adversary and through conflict was crowned with the crown of incorruptibility (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History V.1.41-2).

Blandina, quite literally, goes to the cross as her savior before her. Astonishingly though, the other martyrs did not simply see a brave champion, but Christ himself, in the form of this small woman. By ‘putting on Christ’, the other Christians are encouraged and exhorted to cling to Christ who is our means to fellowship with God.

Who reigns victorious?

Blandina’s strength is astonishing—and I don’t mean to diminish her faith and stamina in any way. But we must be careful to note why she is held in such high regard. It is not her strength in the face of violence, it is not her resolute statements or even the way in which she exhorts her fellow martyrs, it is her humble reflection of Jesus Christ. In Blandina, we have an example of devotion that in some ways renders her invisible—she point us to Christ, rather than herself.

Many women (and men) from church history are now invisible—not because they are unimportant or left no marks. It is because many served Christ in such a way that they are no longer seen, by pointing to Christ through their actions and their character. In them, we behold Christ. And therein lies the paradox of our Christian heroes like Blandina. We should not glorify strength or valor, but those who cling to Christ—our “great and invincible champion.”