Antonio the Negro arrived in Virginia in 1621, which means he witnessed the devastating attacks of Opechancanough upon the Chesapeake settlers during the following year. He narrowly survived these attacks and continued to labor for the Bennett family for a dozen years. Due to his faithful service to the Bennetts, he eventually earned such favor from the family that he obtained a freedman’s status for himself, his wife, and his children, sometime after 1635.

No longer known as Antonio the Negro, by 1647 the freedman Anthony Johnson had purchased livestock and settled a 250-acre head-right adjacent to the Bennetts. As overseer of a head-right plot, Johnson had at least four indentured servants working his land. His sons also settled respectable sized plots of land for planting tobacco. John Johnson received a patent for a 550-acre allotment, and Richard Johnson owned a 100-acre estate.

Despite Anthony Johnson’s seeming success as an industrious freedman and tobacco planter, his achievements attracted ire from white neighbors. A suspicious 1653 field fire damaged his plantation enough for Johnson to file for tax relief through the county court. As a result, his wife and daughters were exempted from taxes for their natural life.

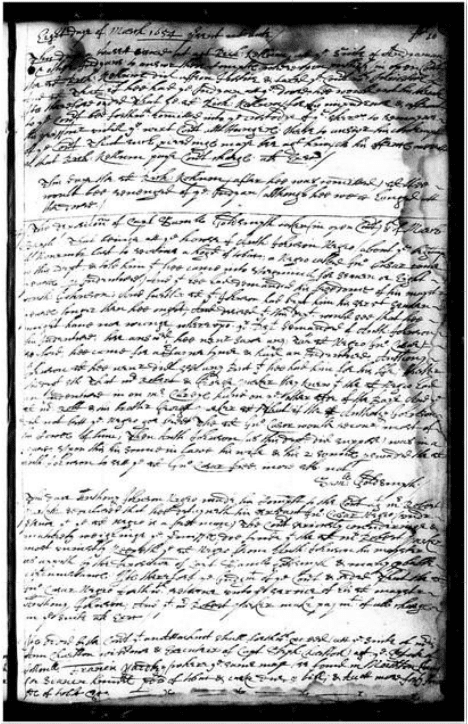

The following year, a black indentured servant of his, John Casor, fled the plantation and sought refuge at the Parker plantation. Not wishing to antagonize the Parkers, Johnson at first did nothing in response. Eventually, Johnson took his neighbors, Robert and George Parker, to court for harboring the fugitive servant. Initially the court ruled in favor of the Parkers, but through an appeal, the court overturned its original decision and ruled in favor of Johnson on March 8, 1655. John Casor was returned to his master.

Nonetheless, Johnson found himself back in court two years later when Edmund Scarborough sued him for an unpaid debt. Scarborough produced a letter in court, purportedly written by Johnson, in which Johnson acknowledged the debt to Scarborough. Despite the fact that the letter must be a forgery, the illiterate Johnson chose not to contest the case and turned over 100 acres of his land to Scarborough in payment of the debt.

Throughout this time, Johnson was counted among a few hundred Atlantic Creoles working Chesapeake plantations. However, the profile of the colony was about to change rapidly. In 1661, Virginia codified its first slave law, allowing any freed person the right to own chattel slaves, and a 1662 law reversed English Common Law and ruled partus sequitur ventrem, that is, children inherited the same social status as their mothers.

Perceiving the solidified racial hierarchy that was emerging in Virginia, it would be during the same decade of the 1660s that the Johnson family would vacate the colony and move to Somerset County, Maryland. Rather than own land in Maryland, Johnson would sign a 99 year lease on a 300-acre plot for tobacco planting that he would call Tories Vineyard. Originally, the agreement concerning this plot of land was that the lease would pass on to his children to manage. However, upon Johnson’s passing in 1670, the land reverted to the ownership of a white colonist, rather than Johnson’s children.

Not only would Anthony Johnson have to withstand the unbearable weight of his own troubles with white planters, but he would have to endure witnessing the same sort of despicable treatment to his sons. The same Parkers, which Johnson took to court in 1654, would accuse his son, John, of “fornication and other enormities.” And sometime during the 1660s, John Johnson would have to produce the record of his Christian baptism in court, in order to validate his freedman status and right to testify.

Disheartening acts of racial aggression would continue to be the specter that haunted the Johnson family all the way to Maryland, where a judge would rule that Johnson’s 99-year lease would not pass onto his children because he was “not a citizen of the colony,” for he was black.

Yet, as Ira Berlin asserts concerning the Johnsons: “Anthony Johnson’s primacy and ‘unmatched achievement’ have made him and his family the most studied members of the charter generation in the Chesapeake” (Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone).

The Johnsons are one of the surprising exceptions to the rule of Atlantic Creole chattel slavery in the Chesapeake. Yet, the perpetual animus this family faced from their white neighbors speaks a louder story still. Even when a black freedman has the right to change his name, purchase livestock, receive tax relief, reclaim his property in court, appeal an unfair ruling, and turn over property in payment of a debt—all along, the undergirding hostilities and adversities that he faced were not the result of poor decisions, foolish behavior, or just plain old suffering. Rather, his hardships were racially determined; he was the target of racial hostility.

On one hand, we can commend the Johnsons for their resilient spirit and celebrate the many ways they subverted the emerging racial hierarchies that oppressed them. But, on the other hand, commending and celebrating is not only not enough, but, potentially a distraction intended to avoid coming to terms with ugly realities. The story of the Johnsons ought to compel us to lament that they had to face racially determined adversity to begin with, and, furthermore, their story ought to prompt us to probe and explore the extent to which we have been complicit in other forms of racially determined adversity up to this day.