Summer for professors often means reworking classes or developing new courses, along with doing our own research. For me, this summer held a bit of both: time working on a new book project and time revising my course on the first half of world history, from the earliest civilizations to the present. And in working on both things, objects, material culture, and what we leave behind kept coming up as common themes.

Material cultural naturally arose during my preparation for my World history course, as the new assigned textbook is Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects, the book connected with the BBC show of the same name.  MacGregor, who works at the British Museum, seeks to tell the history of the world not through traditional frameworks like written sources but through the objects that have survived (and are, in this instance, held in the British Museum). It’s a fascinating read that gives a very different view of world history: the societies that usually get the most attention, like Babylon or Greece or the Franks, appear far more rarely than you might expect, with societies from ancient India or Peru or North America getting far more attention than they do in most world history books. I found this to be a fascinating shift in perspective; by decentering the usual prioritization of texts, other societies, with their own early and complex forms of political, religious, and social organization, become clearer. But a second interesting shift was in the way MacGregor’s narrative shows a different perspective on what each society valued. So many of the objects in MacGregor’s book emphasize power, status, or sex– and not just objects that belonged to rulers or those you might expect. Even things initially intended for ordinary use, like a jomon pot from Japan, were eventually repurposed to highlight wealth and status. It seems that everybody really does want to rule the world, or at least dress and furnish their house like they do.

MacGregor, who works at the British Museum, seeks to tell the history of the world not through traditional frameworks like written sources but through the objects that have survived (and are, in this instance, held in the British Museum). It’s a fascinating read that gives a very different view of world history: the societies that usually get the most attention, like Babylon or Greece or the Franks, appear far more rarely than you might expect, with societies from ancient India or Peru or North America getting far more attention than they do in most world history books. I found this to be a fascinating shift in perspective; by decentering the usual prioritization of texts, other societies, with their own early and complex forms of political, religious, and social organization, become clearer. But a second interesting shift was in the way MacGregor’s narrative shows a different perspective on what each society valued. So many of the objects in MacGregor’s book emphasize power, status, or sex– and not just objects that belonged to rulers or those you might expect. Even things initially intended for ordinary use, like a jomon pot from Japan, were eventually repurposed to highlight wealth and status. It seems that everybody really does want to rule the world, or at least dress and furnish their house like they do.

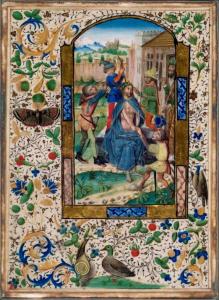

Reading this history of the world through objects paired in striking ways with my time in the United Kingdom, wandering through medieval cathedrals and into archives to work on a book project on emotion, religion, and gender in the Middle Ages. Like the objects in MacGregor’s study, the objects around me reflected the priorities and values of the medieval people I was studying. Gilded books of hours like the Bolton Book of Hours, cathedrals like the York Minster, and even less pretty sermon or play manuscripts: all of these objects pointed to an emphasis on building heavenly treasure through earthly treasures meant to worship and glorify God. It’s striking not just how many of these earthly iterations of heavenly treasure survive, but also how many are now used for different purposes, like a medieval parish church converted into a coffee shop. Medieval Christians would be surprised, I think, to see how differently some of their treasures are now used and the way that the priorities of the community have changed in some ways.

All of this got me thinking about the objects we’re leaving behind today and what those objects say about our priorities. Does a lack of beautiful churches indicate a lack of emphasis on faith, or a renewed emphasis on investing money and resources into people rather than buildings? If someone considered our priorities through looking at what objects we have in our houses, what would they think we value and prioritize as a society? And as Christians, do the objects we leave behind look any different than the objects in the houses of those who are not believers? If they don’t, shouldn’t they? But in what ways?

I’m not sure I have answers for any of these questions. It seems to me that as Christians, whose faith should form and shape every aspect of our lives, the objects we leave behind should look different in some way. I tend to think we should aspire to have less of them, to invest more of our resources into the people and communities we live in, into efforts to bring about justice and spread the Gospel. But I also think that in some ways, our medieval brothers and sisters got something right with their cathedrals and beautiful books. For me, it’s easier to understand the grandeur and splendor of the God we serve when I look around the York Minster, with its stories of scripture and saints in its stained glass and its soaring stonework. There’s something to be said for honoring God through investing the time and resources into art and material culture as a form of worship. So maybe one answer is that when we think about what we leave behind, we need to leave behind both objects and a lack of objects. We should work to create testaments to God’s glory that will bear witness to a broader world while also avoiding the pitfalls of power and status that so often come with objects and buildings. At the same time, I have been convicted to think about leaving less behind, about stepping away from modern American trappings of status and style to invest more in making our world more just, more equitable, and more environmentally sustainable. I’m still working out what that looks like in my daily life, but I hope that if someone ever tries to understand my life through the objects I have and leave, it’s clear that loving God and loving neighbor– acting justly, loving mercy, and walking humbly with the Lord– were my priorities.