There is a street in Jerusalem whose history sheds a different, more personal and human light on the prolonged and continuing conflict that is the Arab-Israeli Wars. On the one hand, we see, as this weekend, terrorist organizations and state armies targeting each other, extending further Israel’s liturgy of national suffering—but that of the Palestinians as well. The death tolls are devastating, but seeing such numbers simply listed as tallies in news headlines lends a detached, impersonal air to wars. But on the other hand, on this street over the past seventy-five years, Israeli and Palestinian neighbors have shared and exchanged meals, bouquets of flowers, notes, cigarettes, but also curses and cast rocks. Some have died here too, not all a natural death. The street has at times been called “No Man’s Land,” “Barbed Wire Alley,” and at last, “Assael”—meaning, “Made by God.”

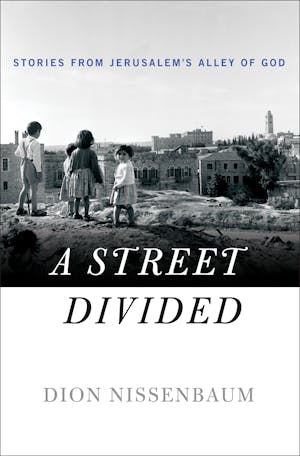

Historians look at events from both macro and micro level. As with all things in life, sometimes zooming in changes the story dramatically. So it is with the story of this street. If I could recommend just one book for someone without much knowledge of the history of the Israeli and Palestinian conflict, I would recommend journalist Dion Nissenbaum’s lyrical history of Assael, A Street Divided: Stories from Jerusalem’s Alley of God.

Why this book, out of everything you could possibly go forth and read, wading into the weeds of Middle Eastern and global politics? Because, again, our viewpoint—perspective—changes entirely with such a narrow focus. A large picture perspective leads researchers and observers to try and take sides: someone in this horrific conflict must be in the right or in the wrong. Someone will be the winner or the loser in the war. But this kind of narrative that generalizes the character and agency of nations wholesale is misleading. Nations are made up of individual people, and those individual people may have entirely different sorts of preferences and views. Put simply, individual people would usually prefer peace over war.

When we zoom in to consider the wars and conflicts through just the history of “one 300-yard, dead-end street in one little city,” we learn instead that the history of Arab-Israeli wars is not just a history of state violence, but is made up also of the stories of real people who wanted to live regular lives—raising children, taking care of elderly relatives, celebrating birthdays and weddings and religious festivals, pursuing an education and career, and looking for that best bread recipe. These are the “normal” things of life that we all crave, but war disrupts them. Larger narratives of war that focus merely on national guilt or innocence ignore their existence altogether, reducing civilians to “necessary collateral damage,” when they suffer as a result of these wars.

In other words, when we look at a 75-year cycle of war and violence from the perspective of a single street, something different becomes clear: this conflict is an external force imposed on residents who would much rather prefer peace.

Consider the 1956 international cease-fire on this street, then a No Man’s Land guarded intensely by both Israeli and Jordanian snipers. Cause of the cease-fire? A cancer patient in a French Catholic hospital on this street accidentally knocked her dentures out of the window. Nuns and soldiers worked together to locate the dentures, and the picture of one of the nuns, triumphantly waving her find in the air, made it into Life magazine, although “the French commander who led the search party complained that it made him look like a fool.”

In some ways, this commander’s disgust with this humanitarian gesture exemplifies the contrast between how individuals view war and peace and how states and their militaries think of it. Presumably, this same commander would have been delighted to be photographed looking victorious following a battle or skirmish. A kindness to a woman dying of cancer, by contrast, seemed an embarrassment for him.

Then in 1967, the result of the Six Day War was the reunification of Jerusalem under Israeli control. The barbed wire dividing the street came down. The stories that emerged from this period are striking. There are the heartfelt stories of neighbors, Jewish and Muslim, looking out for each other. For the Arab-speaking Jewish immigrants, indeed, their Palestinian Arab neighbors seemed culturally closer than even other Jews on the street. But bullies and hooligans emerged as well. Still, some refused to give up, and the book is filled with their stories.

One of Nissenbaum’s examples, indeed, is the story of one Israeli resident of the street who had tried to organize peaceful cooperations and shared activities between both Jews and Palestinians in the larger Abu Tor neighborhood in which Assael is located. At last, he realized that even smaller-scale change matters: “The young David dreamed about changing the world. By the time he was ready to retire, he’d come to realize that changing his neighborhood was hard enough.” But he still “likes to think that what he’s doing matters to more than just the people on his street.”

Still, no street exists in a vacuum, and resist it as they might, its residents have not been able to keep war out. When Palestinians kidnapped and killed three Jewish Israeli boys in the West Bank in 2014, tensions escalated. There was, in direct response, the horrific kidnapping and murder of a Palestinian teenager in East Jerusalem by three Israeli Jews—a revenge killing that shocked Jews and Palestinians alike. Israel’s war in the Gaza strip followed shortly after, with a devastating toll on civilians—albeit likely not nearly as devastating as the war that erupted this weekend promises to be. Indeed, the deliberate and cruel targeting of civilians–women, children, the elderly in wheelchairs–that was the signature move of this weekend’s attacks, is unprecedented in Israel’s history. Healing from trauma like this will not be easy. But through all of the traumas of the rounds of violence in 2014, Jerusalem Youth Choir continued to include both Jewish and Palestinian members, many of whom knew one or more of the killed teens at the West Bank or East Jerusalem. And these teens continued to come to choir practice, recording a viral YouTube video of a song appropriately titled “Home.”

Perhaps their story offers the most poignant takeaway from Nissenbaum’s attempt to zoom in to consider everyday life on this single street. It is special in some ways and utterly unremarkable in others. At the end, every square inch of the overcrowded land that is Israel is home to someone. And what most of these people want to do is just live their lives.

When I first read this book a couple of years ago, in preparation for teaching it in a class “Jerusalem: Three Thousand Years,” I walked away from it with a sense of cautious optimism. Good things can yet come of it all. Regular people can be stronger at the street level than heavy-handed forces of nations and leaders. I believe this is still true, but what Hamas did this weekend was precisely an attack on this source of peace–the work of civilians who want to love their neighbors.

I am a historian, not policy analyst. My only power–and a very limited one it is–resides in my words. But what I want to say here is something that I firmly believe as a citizen of both Israel and the United States, and as someone who spent a good portion of her growing up years in Israel and came to Christ as an adult: God loves the weak. He does. And he loves the weak who pursue peace with love, kindness, and gentleness. How does this translate into national or international policy? Perhaps it doesn’t. But at the street level, it does.