My current work involves the topic of Lived Religion, which over the past few decades has come to represent a major theme in religious studies scholarship. Briefly, it represents the study of what people actually do in religious matters, independent of official dogmas or institutions. In the words of the French founders of the idea, lived religion, religion vécue, is distinct from “prescribed religion”, religion prescrite. That is today a very familiar idea. But what interests me is how those real-world practices of everyday religion echo each other across different faiths, even if the case-studies are widely separated in time and space. It almost looks as if we are finding universal human responses, regardless of whether the practitioners are notionally Christian, Muslim, Hindu, or other.

Let me offer a case study of such “echoing.” I will first offer an example from the Christian religious experience, but then suggest how very closely, and almost shockingly, it reflects Islamic realities. There is no conceivable path of influence between the two. Both sides just suffered from a common condition called “being human.” Together, the examples give us a good sense of what we might call the default religion of the pre-modern world.

Popular Christian Devotions

In the Middle Ages, European Christians developed a very wide range of religious practices and devotions, usually with the full support of the church. At the Reformation, most of those practices were condemned by the new Protestant religious establishments, which enforced their views with varying degrees of severity. However, older ways survived in regions far removed from the reach of authority, whether civil or religious, and some of those survivals were impressive.

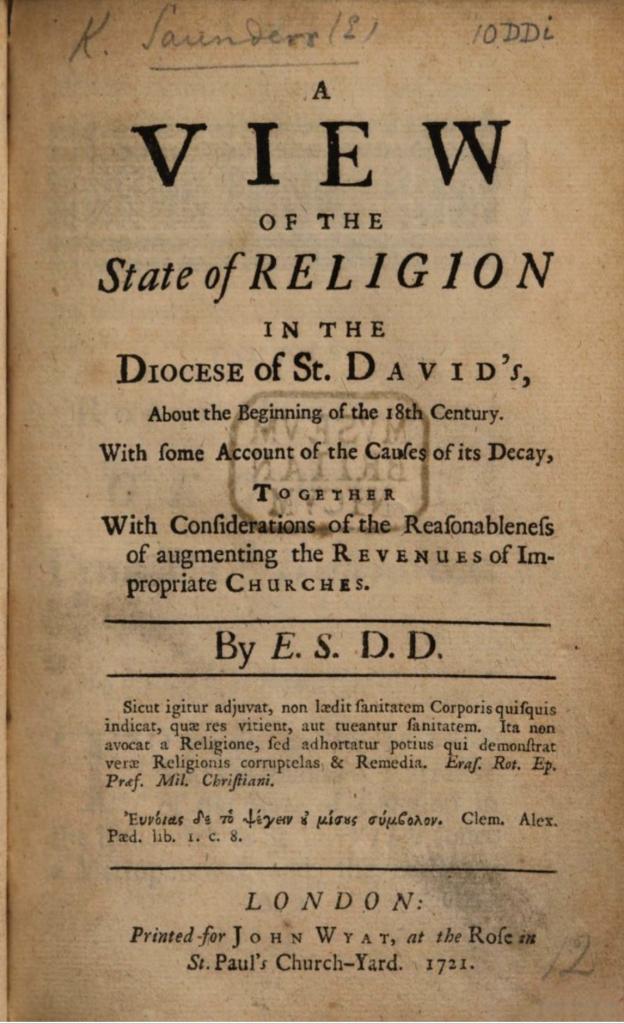

I have previously blogged at this site about a much-quoted source about religious life in one remote corner of the British Isles in the early eighteenth century, more than 150 years after the notional success of the Reformation. In 1721, Welsh Anglican cleric Erasmus Saunders (1670-1724) published his book A View of the State of Religion in the Diocese of St. David’s, About the Beginning of the Eighteenth Century, With Some Account of the Causes of its Decay, together with Considerations of the Reasonableness of Augmenting the Revenues of Impropriate Churches. The title says it all. Saunders was describing the historic Welsh diocese of St. David’s, which covered a large and thinly populated area of south and west Wales. The church operated through large and miserably poor funded parishes, so that its footprint was exceedingly light, and most people rarely had access to religious services. The physical condition of the churches was parlous, and most were semi-ruinous. The solution to this crisis, thought Saunders, was giving more money to the parishes whose tithes had been lost.

For present purposes, Saunders’s work is invaluable for what it says about the lived religion of a society passionately interested to forms of spirituality, but operating largely free of any official sanctions. He portrays the wide survival of older customs that closely follow medieval devotions, but which may conceivably include some pagan remnants, and free-floating superstitions. He describes these manifestations with horror, and that attitude is reflected by the many later historians who quote him to demonstrate just what a spiritual desert Wales was before the evangelical revivals of the eighteenth century. Please read that earlier blogpost of mine for details of his complaints, which I quote at length, and will not repeat in detail here (and see also this post). Here is an extract:

There is, I believe, no part of the nation more inclined to be religious, and to be delighted with it, than the poor inhabitants of these mountains. They do not think it too much, when neither ways nor weather are inviting, over cold and bleak hills to travel three or four miles, or more, on foot, to attend the public prayers— and sometimes as many more, to hear a sermon; and they seldom grudge many times for several hours together, in their damp and cold churches, to wait the coming of their minister, who by occasional duties in his other curacies, or by other accidents, may be obliged to disappoint them and to be often variable in his hours of prayer.

Saints, Shrines and Pilgrims

Faith was not in short supply, but the problem, from a Protestant view, was that so much of this devotion was expressed in very medieval and Catholic-looking terms.

Another ancient practice, namely that of crossing themselves, as the first Christians were wont to do upon many occasions, is much in use among them, with a short ejaculation that through the Cross of Christ they might be safe or saved.And as we are told by Eusebius and others, that the first Christians were wont to meet at the graves of martyrs, and others of their deceased friends to say their prayers there, and to pay some respect and honor to their memory, there is also something of the same kind that is observed here. In most mountainous parts, where old customs and simplicity are most prevailing, there we shall observe that when the people come to church, they go immediately to the graves of their friends, and there kneeling, offer up their prayer to God; but especially at the feast of the Nativity of our Lord ; for they then come to church about cock-crowing, and bring either candles or torches with them, which they set to burn, every one, one or more upon the grave of his departed friend, and then set themselves to sing their carols, and continue so to do, to welcome the approaching festival, until prayer-time.

But with these innocent good old customs, they have also learned some of the Roman superstitious practices in the later ages, such as many times in their ejaculations to invocate not only the Deity, but the Holy Virgin and other saints; for Mair-Wen [Holy Mary], Jago [James], Teilaw Mawr, Celer, Celynnog and others are often thus remembered as if they had hardly yet forgotten the use of praying to them. And there being not only churches and chapels but springs and fountains dedicated to those saints, they do at certain times go and bathe themselves in them, and sometimes leave their small oblations behind them either to the keeper of the place or in a charity box prepared for that purpose by way of acknowledgment for the benefit they have, or hope to have thereby. Nay, in many parts of North Wales they continue in effect still to pay for obits, by giving oblations to the ministers at the burial of their friends, as they were formerly taught to do to pray them out of purgatory, without which useful perquisites the poor curates in many places would be very hard pushed to get their livelihood.

And thus it is the Christian religion labours to keep ground here. Superstition and religion, error and truth, are so very oddly mixed, that it should in charity be concluded to be rather the misfortune of many that they are misled. For the generality are, I am afraid, more obliged, if not to their natural probity, to their religious observance of those ancient customs, or to the instruction that they get from their carols, or the Vicar of Llanymddyfry’s poems, than to any benefit received from the catechizing and preaching of a regular ministry.

Other evangelical reformers offered accounts of Wales very similar to Saunders, so he was clearly not making up his allegations. Moreover, we find very similar accounts elsewhere in the British Isles and in Western and Northern Europe more generally, in such notorious “dark corner of the land.” These were the same subterranean worlds of religion and superstition that anthropologists were collecting across well into the last century.

Saunders is describing what we might term a “ghost religion,” the faith of what had been a clerical/priestly religion once those clergy and priests are removed. What remains four or five generations later? I highlight several obvious points:

i.Most obvious is the continuing need for religious practice of some kind, whether or not that is approved by the official church.

ii.People retain their veneration for the holy names and figures of the old faith, even if they actual knowledge of them is limited.

iii.They retain core customs that sanctify and sacralize everyday life, such as crossing themselves. In Catholic language, they love the sacramentals, those habits and customs that fall short of being central dogmas or institutions of the faith, but which are still so deeply loved. Candles and sources of light provide a universal spiritual symbol.

iv.Their religious ideas have a strong element of material holiness, the idea that special power resides in objects.

v.Following directly on from that, believers know that power and holiness reside in special places, from which healing and other benefits can be sought. Wells and other sites are thin spaces, points of transition between worlds.

vi.Holiness is especially to be found in individuals of particular merit, charismatic saints who have gained a special place in the heavenly realms, and to whom ordinary mortals can turn for assistance.

vii.People know and keep a ritual calendar, in which days and seasons have special value and holiness, calling for particular actions. The Christmas season is pivotal.

viii.Regardless of any theological doctrines, people are deeply conscious of the spiritual well-being of their friends and relatives after death, and think that what they do in this world can assist the departed. As with the instance of the saints above, this suggests a belief in connections and continuities between the two realms. Death is central to faith.

ix.People believe that those who receive spiritual services or benefits should supply material goods in exchange. That does not necessarily mean that such services are for sale, but rather than exchange and sacrifice are a basic part of life in this world and the other.

x.All these ideas are expressed and reinforced through popular story-telling and superstition, which supplement or replace official religious teachings.

Although the holy figures and the ritual calendar are explicitly Christian, basically nothing of what is recorded here in any way reflects Christian theology, whether Protestant or Catholic. Interestingly, Christ himself scarcely appears in this religious thought-world, nor do such critical doctrines as the Trinity, or Incarnation, or Atonement, or Resurrection. This is a religion of holy places where holy people are commemorated and, ideally, contacted and petitioned.

Through an Islamic Mirror

All the people Saunders is describing would unhesitatingly describe themselves as faithful Christians. If however we shift our focus to other parts of the world – to North Africa or Central Asia or South Asia – we find a very large number of people doing essentially the same things as those in Wales, fulfilling all the points in the list I just enumerated, and they would with equal conviction call themselves faithful Muslims.

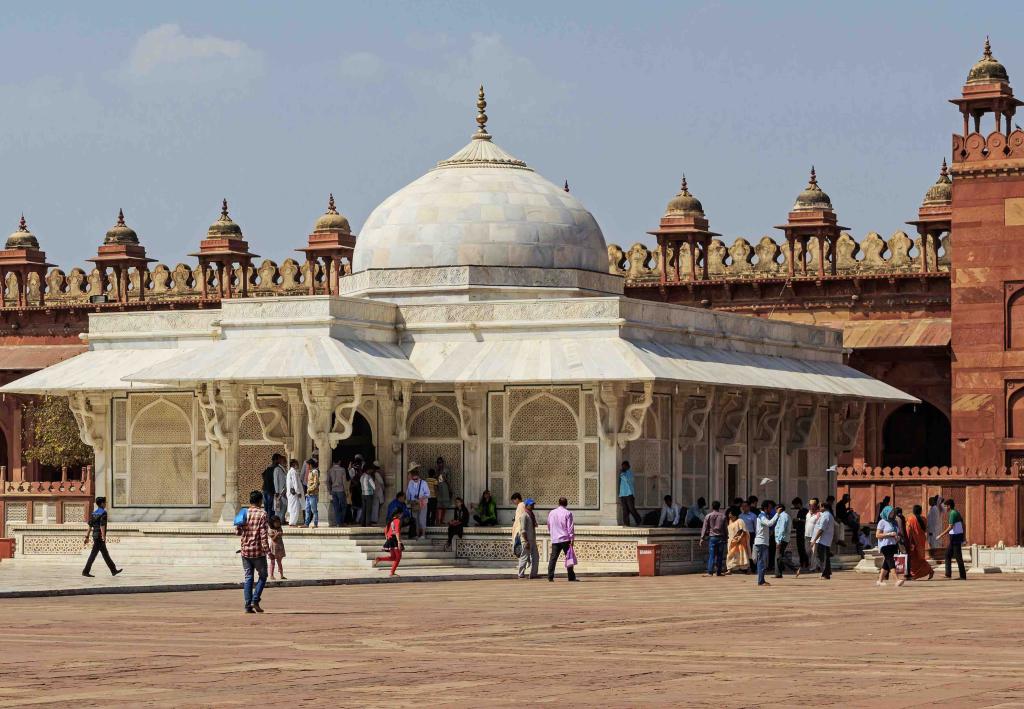

In modern times, and under the influence of reformist and fundamentalist movements, the normal practice of Islam has come to be more austere and defined by clerical orthodoxy than in virtually all previous eras. Around much of the world, until very modern times, the normal and approved practice of faith focused on the work of mystical Sufi orders, whose rituals involved music. The deceased former leaders of the sect were commemorated at shrines that became the center of pilgrimage, to which faithful believers resorted for blessings or healing. This was the standard nature of “lived” Islam across most of its territories for centuries. (I hasten to add that the Sufi orders were firmly part of the orthodox Islam of their time, and in no sense some kind of deviant or heterodox sect).

Those shrines are commonly known by the Persian word Dargah, which combines two words meaning “door place”, a portal or threshold – an intriguing name in its own right, which corresponds nicely to “thin space.”

Such shrines are the settings for festivals that celebrate the saint on the anniversary of his passing. Those events involve plenty of candles or, in modern times, electric lights. They are also the venue for musical performances, often of very high artistic quality. If you want to get a sense of how these devotions work, and how they dominate spiritual sensibilities, you could do much worse than to read Erasmus Saunders’s accounts of Christian Wales three centuries ago.

In the Levant, James Grehan’s excellent 2014 study of Everyday Religion In Ottoman Syria And Palestine memorably reconstructs a faith based on the veneration of holy individuals, whose tombs are visited by the faithful, but these form part of a whole sacred landscape marked by stones, caves, water, and trees. No less central to religious life are protective amulets and talismans, and a potent belief in dreams and visions. Grehan aptly terms this assemblage of practices “agrarian religion,” suggesting its broad relevance to pre-industrial societies within the Islamic world and beyond.

Even in recent times, such ideas persist. In 2012, a Pew survey found that

In most of the 23 countries where the question was asked, majorities endorse visiting shrines of Muslim saints as a legitimate form of worship. This view is especially widespread in Central Asia, Southeast Asia and South Asia. … There is also substantial approval of devotional poetry or singing as a form of worship.

In societies where multiple religions coexist, there is very long evidence of the interfaith sharing of shrines and pilgrimage sites, with a remarkable harmony about the figures venerated there, and the ways in which they are celebrated. Again in the Levant, many shrines have indiscriminately attracted Muslims, Christians and Jews, commonly in devotions to the Virgin Mary, and usually in quest of healing or exorcism. The Marian Christian shrine of Saidnaya in Syria was long popular with pilgrims – with Christians, of course, but also the many Muslims who came on Fridays to pay their respects to the Virgin. Believers of both kinds came for healing, women usually in quest of healthy pregnancies. Such free interchange was the historic norm for over a millennium, and really ended only in the civil wars of the present century.

The Passing of an Old Order

Over the past half century, such devotions have been the focus of what is one of the most important religious developments of modern times. As fundamentalist Islam has become more common, and more rigid, so militants have tried to root out those Sufi devotions, often by armed force. This has involved for instance frequent terror attacks against Sufi devotees and shrines in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and the widespread suppression of sites in Egypt and across North Africa. In the name of reform, such acts constitute a war against what was for centuries the norm and mainstay of Islamic practice, of its lived religion. As in the case of the eighteenth century evangelical reformers within Christianity, those older practices were now denounced as syncretistic, as pagan, and as absolutely not legitimate within the newly defined orthodoxy, the religion prescrite.

The other mighty force undermining Sufi traditions is migration. Most of the Islamic migrants who traveled from North Africa to Western Europe over the past seventy years came from societies where religious faith was dominated by shrines, saints, and sacralized landscapes. All those features were lacking in the new land, where migrant families and especially their children moved to newer and more fundamentalist forms of faith, commonly with an extremist tinge.

On the lighter side, within what is otherwise a very grim and depressing story, you get a great sense of the way in which those older vernacular devotions operate from the 2019 Moroccan film The Unknown Saint. This is (oddly) a rollicking comedy about thieves who bury a treasure in an out of the way location, only to return some years later to find that it has become a popular Sufi shrine to an unknown saint, and they have to find a way to extract their loot. It is well worth watching, not least for the portrayal of the landscape and the shrine itself.

In remarking the many parallels between Christian and Islamic practices, I am in no sense suggesting that those eighteenth century Welsh Christian believers were drawing on Islamic influences (!). Nor were or are the Sufis themselves consciously imitating popular Catholic devotion: if there was any Christian inheritance in lands like North Africa, it was a very distant legacy indeed. Rather, I point out that much religious practice arises from the fact of being human, with our particular life cycle, and our hard wired realities. I have previously called these the building blocks of faith. These provide, if you like, the underlying grammar of our religious behavior, however that manifests in particular traditions. Normally, religious institutions regulate such manifestations, at least to some extent. But when central authority is slim or non-existent, that “underlying” behavior comes back to the fore. And that Erasmus Saunders example offers an excellent example of what it looked like.

Idealists sometimes dream of a “universal” religion. Such a grand unifying theoretical system might never happen, but ordinary religious practices of a pretty “universal” kind are not too hard to seek.