Today we have a guest post on an important historical topic, to which I will offer a short introduction.

I have blogged before on debates over the European settlement of the Americas, and the religious nature of those conquests. One of the greatest turning points in the history of Christianity came with the Iberian conquests in the New World during the sixteenth century, and the spread of the new faith across the whole of those vast continents. Unquestionably, the whole venture raises very serious moral and ethical questions, which become all the more acute the closer we examine the mass forced conversions and the destruction of Native cultures.

When historians tell those grim stories, they commonly cite an episode that occurred in 1562, when the friar Diego de Landa burned many ancient Maya texts. As he recorded,

We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.

As I have remarked in the past, a Christian might regret seeing a persecutor destroying a copy of the New Testament, but just imagine the experience of seeing a book burned, and knowing that it is the last extant copy of some treasured text such as the Gospel of John, which would henceforward be lost irretrievably. “Much affliction” sounds very accurate. De Landa‘s writings are often quoted – but should we take the common story at face value? Does Friar De Landa deserve his dreadful reputation? Most important, how do we know what we think we know about all this?

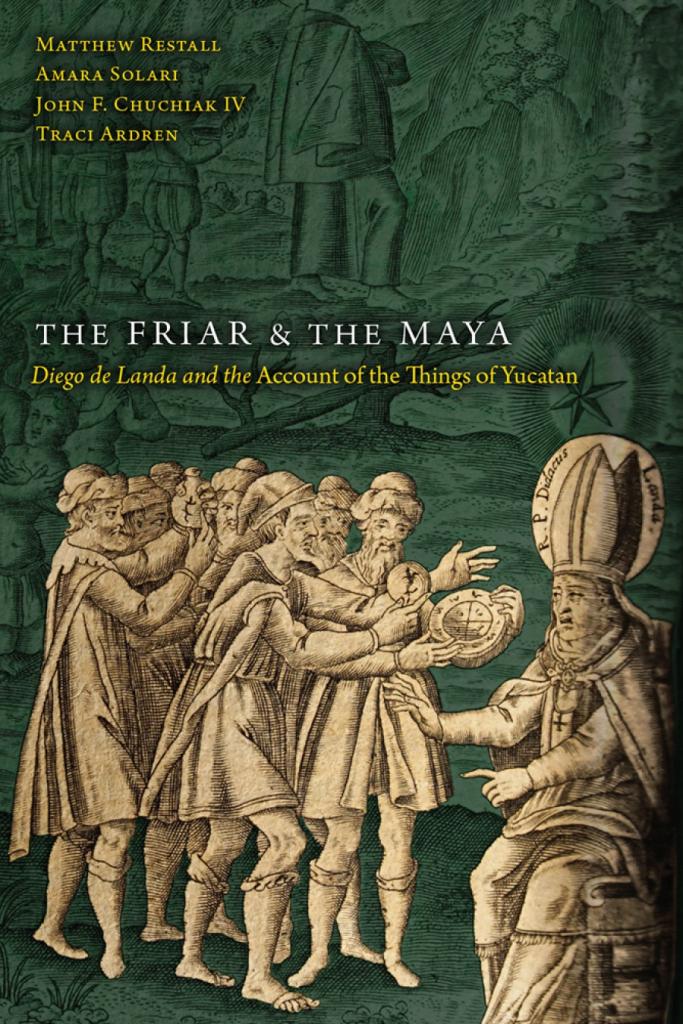

Because those missions and conversion efforts were so critically significant, I am delighted to see the new book by my former Penn State colleague Matthew Restall and his collaborators. The full citation is to Mathew Restall, Amara Solari, John F. Chuchiak IV, and Traci Ardren, The Friar and the Maya: Diego de Landa and the Account of the Things of Yucatan (University Press of Colorado, 2023). This very substantial project promises to rewrite so much of what we thought we knew about the Central American missions of that era.

I invited Matthew to write a post on the new book, which follows below:

THE FRIAR AND THE MAYA

MATTHEW RESTALL

Diego de Landa was the archetypal “spiritual conquistador.” A sixteenth-century Spaniard, a Franciscan friar, and a monastic inquisitor and bishop, he spearheaded the conversion of the Mayas of Yucatan. But he provoked trans-Atlantic controversy with his methods—both protecting the Maya from the new Spanish colonists and ordering “idolatrous” Mayas to be tortured.

Landa wrote extensively on Maya culture and history, and on the tumultuous tale of the protracted Spanish effort to establish a settlement in Yucatan (it took thirty years to establish a small colonial province in the peninsula’s northwest). He created a great recopilación or compendium of his own work, of testimony by Maya informants, and of excerpts from manuscripts by others. At least, that is how other Franciscans described the compendium, for it was lost in the seventeenth century and has never been found.

When a fragment of Landa’s compendium was discovered in the nineteenth century in a small Madrid library by a French abbot, Landa’s controversial reputation was reignited. That reputation burns as brightly today as it ever did. If the famous Dominican friar, Bartolomé de Las Casas, is the stereotype of the “good” missionary in the sixteenth-century Americas, then Diego de Landa is infamous as the “bad” one. Landa’s legacy is thus complex and contested.

That manuscript fragment, dubbed the Relación de las cosas de Yucatán (Account of the Things of Yucatan), was partially published by its discoverer, who gave it chapter titles and treated it as a book by Landa. Landa’s “book” was subsequently published many times in many languages, attaining near-biblical status in the twentieth century as the first “ethnography” of the Maya. Used for generations of scholars as the sole eyewitness insight into an ancient civilization, it is still routinely consulted, cited, and used in the classroom, making Landa the best-known Spaniard to set foot among the Maya.

There is a problem, however. In fact, there is a pair of problems with how the Account has been used—or rather, misused—by generations of scholars of Maya past and of Franciscan evangelization campaigns in Yucatan and Mexico. First, attempts to reconcile Landa’s two seemingly contradictory attitudes towards the Maya—what I call the Landa conundrum—have been perfunctory and often tied to poor grasps of the Account. For example, the paucity of comments in the Account on Landa’s violent 1562 campaign against Maya “idolatry”—including a lack of expressions either remorseful or defensive—offers no evidence of Landa’s mentality; it merely reflects the nature of the text. Landa was able to reconcile his pastoral commitments with his decision to inflict violence upon those he perceived as recalcitrant, making it incumbent upon us to dig deeper to understand him—and to understand why the Account does not offer simple answers.

Second, the Account cannot be edited into a coherent book written by a single author—because it is no such a thing. As a collection of excerpts made from a long-lost compilation of texts, it comprises various voices, authors, sources, and styles. Put simply, the Account is not authored by Landa alone. The fact that it includes excerpts from writings by other Spaniards and by Maya informants is a significant revelation made here, in detail, for the first time.

I am part of a team of four scholars who have created a new edition of this influential text for English-speaking readers, one that explores rather than disguises the true nature of the text. That team consists of art historian Amara Solari, historian John Chuchiak, archaeologist Traci Ardren, and me, also an historian. Our volume, titled The Friar and the Maya: Diego de Landa and the Account of the Things of Yucatan, published this month by the University Press of Colorado, comprises a seven-chapter monograph, a fully annotated translation of the Account, and a quarter of the original text in facsimile (prioritizing those pages with drawings—including Maya glyphs—and those pages showing shifts in handwriting and other significant features of the surviving manuscript). All chapters and notes are co-authored, being the product of two decades of conversation and composition, with occasional differences of opinion aired in footnotes.

We hope that this is the critical and careful reading of the Account that is long overdue in Maya Studies, and that it will forever change how this seminal text is understood and used. I would not claim our edition is “definitive”—as I doubt any edition of any historical text can be such a thing—but I do anticipate it will serve as the basis for debate, discussion, and long-term rethinking.