Well, this is not the kind of subject matter that people normally address when planning their Christmas sermons, but bear with me…

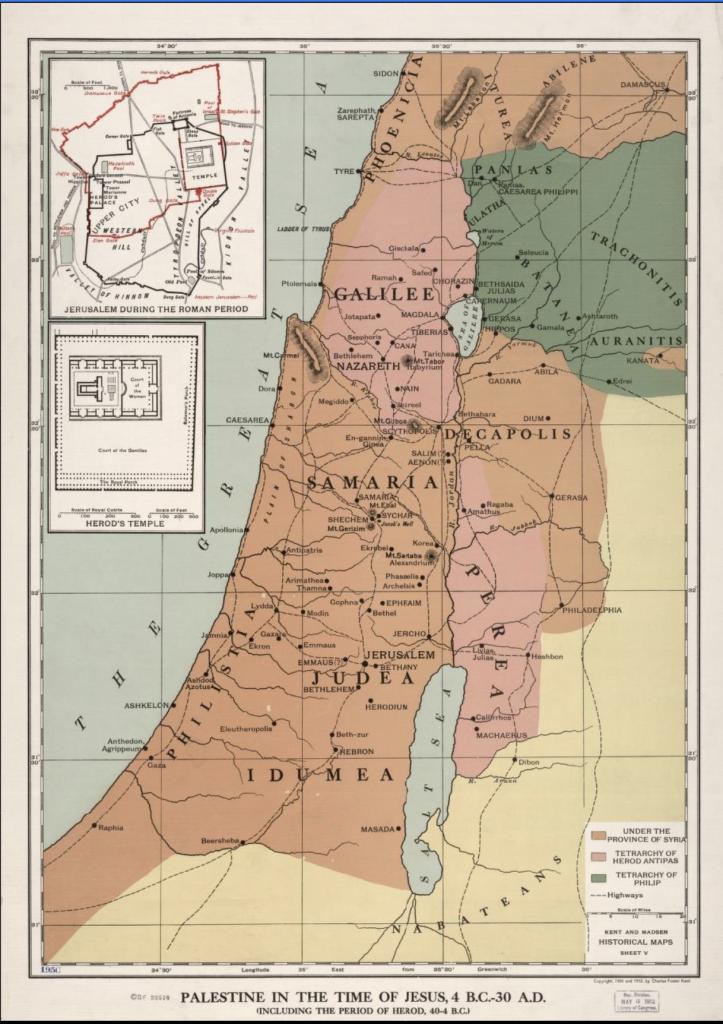

Scholars differ on the exact birth-date of Jesus of Nazareth, though a fair consensus holds that it was not in the year 1. Many favor a date in or around 4 BC, and for the sake of argument, let us take that as accurate. If so, the birth occurred during or near a truly dreadful time in the history of what was already a troubled and turbulent land: arguably, the story has a special new relevance in the horribly violent conditions in that region today. Although these events are familiar to scholars, they are not at all well known by non-specialists. This is unfortunate, because memories of this crisis certainly shaped memories and perceptions for decades afterwards, and conditioned attitudes during Jesus’s lifetime. If we don’t understand those conflicts, we are missing the prehistory of the earliest Jesus Movement. And they do provide a necessary, if unsettling, context for the Christmas story we recount at this time of year. Was this really what that first Christmas was like?

King Herod the Great died in 4 BC, amidst political turmoil and religious unrest. Immediately following his death, the country entered a period of insurgency and violence that in many ways foreshadows the very well known events of 66 AD, the famous “Jewish War” commemorated by Josephus. Although on a much smaller scale than that later catastrophe, the earlier crisis demands to be remembered for multiple reasons.

So poorly remembered are these events that they do not even bear a convenient name. Suggested names include the War of Varus and the First Judean War, and the Archelaean Revolt might be another candidate. None of these names, though, is terribly satisfactory, and emphasizing Varus really underplays the extensive history that occurred before his direct intervention.

My main source for the story is chapter seventeen of the Jewish Antiquities of Josephus, which has provided the material for multiple modern accounts. There is of course a substantial overlap with the early chapters of the same author’s Jewish War. I discuss these topics more in my 2017 book Crucible of Faith.

By 4 BC, Herod the Great was coming to the end of a long career that was bloody and paranoid even by the standards of Hellenistic monarchies. (He had held power since 37 BC). He ruled through tactics of mass terror and widespread surveillance that sometimes sound like a foretaste of the Stalin years. He had killed multiple members of his family, and in the year 4 was in the process of trying and executing his son Antipater for alleged treason. He also systematically wiped out all male claimants from the old Hasmonean royal dynasty. According to Matthew’s Gospel, that same desire to exterminate potential rivals drove him to slaughter the innocent children of Bethlehem.

No matter how violent, palace intrigues need not have a wider public impact, but Herod’s growing paranoia and mental illness was becoming a scandal among other rulers, and was presumably well known to any educated member of the Jewish elite.

The question then arose what would happen when Herod died. For 150 years, Jewish Palestine had been deeply divided between warring factions, whose conflicts had been kept in check by Herod’s equal opportunity reign of terror. During Herod’s reign, also, domestic conflicts found a new focus in the response to Roman overlordship. Herod was a Jewish king, but he also had to rule as a Mediterranean monarch, supporting the public symbols and spectacular performances that that entailed. Such activities outraged religious-nationalist opinion as an egregious display of idolatry. Might Herod’s death mark the rebirth of a purified and independent Jewish state?

The crisis reached a perilous new phase when two Jewish activists, Matthias and Judas, destroyed the imperial eagle that Herod had ordered erected at the Temple gate. Reportedly, they did this on the strength of a false rumor that Herod lay dying, so that a new era was at hand. Herod responded furiously, burning alive the two main perpetrators and killing their accomplices. However, his death very shortly afterwards meant that he could not take the wider vengeance that he perhaps would have done earlier.

Herod’s death aroused hopes of a new regime under his successor, Archelaus (who was then just nineteen). “The people” assembled to demand that the new ruler punish those who had been favorites of Herod, and that the high priesthood should be given to a new incumbent. They also wanted their taxes reduced. Archelaus was justly terrified of open revolution, all the more so given the approach of Passover, when the city would be filled with outsiders from the countryside. He ordered his forces to watch out for open sedition, but the resulting intervention went far beyond rounding up the usual suspects:

But those that were seditious on account of those teachers of the law, irritated the people by the noise and clamors they used to encourage the people in their designs; so they made an assault upon the soldiers, and came up to them, and stoned the greatest part of them, although some of them ran away wounded, and their captain among them; and when they had thus done, they returned to the sacrifices which were already in their hands. Now Archelaus thought there was no way to preserve the entire government but by cutting off those who made this attempt upon it; so he sent out the whole army upon them, and sent the horsemen to prevent those that had their tents without the temple from assisting those that were within the temple, and to kill such as ran away from the footmen when they thought themselves out of danger; which horsemen slew three thousand men, while the rest went to the neighboring mountains.

As so often in ancient sources, it would take a brave historian to swear that the number killed was three thousand, no more and no less, but we can confidently speak of a significant massacre. Archelaus immediately issued a proclamation canceling the Passover feast.

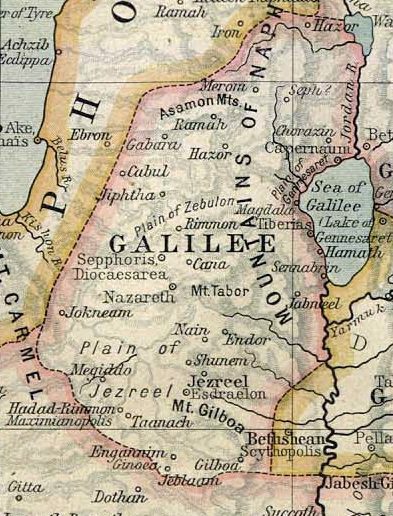

Similar disasters followed at Pentecost. “A countless multitude flocked in from Galilee, from Idumaea, from Jericho, and from Peraea beyond the Jordan, but it was the native population of Judea itself which, both in numbers and ardor, was pre-eminent.” The mob besieged the Roman garrison, leading to another bloody battle, in which the Jews were alarmingly undaunted by their Roman enemies.

Conflict raged far beyond Jerusalem. According to Josephus,

Now at this time there were ten thousand other disorders in Judea, which were like tumults, because a great number put themselves into a warlike posture, either out of hopes of gain to themselves, or out of enmity to the Jews. … And now Judea was full of robberies; and as the several companies of the seditious lighted upon any one to head them, he was created a king immediately, in order to do mischief to the public. They were in some small measure indeed, and in small matters, hurtful to the Romans; but the murders they committed upon their own people lasted a long while.

No less than three (unrelated) popular leaders emerged to claim the role of popular king. One was Judah, son of Hezekiah, a bandit leader killed by Herod. Judas took the city of Sepphoris (barely four miles from Nazareth), seizing its arms and wealth, and distributed them to his followers. Another would be king was Simon who

burnt down the royal palace at Jericho, and plundered what was left in it. He also set fire to many other of the king’s houses in several places of the country, and utterly destroyed them, and permitted those that were with him to take what was left in them for a prey; and he would have done greater things, unless care had been taken to repress him immediately.

The last of these “kings” was a shepherd named Athronges, whose main qualification for office seems to have been his unusual height.

The Romans duly called for help from the governor of Syria, P. Quinctilius Varus, then based in Antioch. He brought in a very substantial force of two legions, plus allied and auxiliary forces, among whom was Aretas IV, the Nabatean, king of Arabia Petrea:

When he had now collected all his forces together, he committed part of them to his son, and to a friend of his, and sent them upon an expedition into Galilee, which lies in the neighborhood of Ptolemais; who made an attack upon the enemy, and put them to flight, and took Sepphoris, and made its inhabitants slaves, and burnt the city.

Just a few miles away, there would have been living at this time a young couple named Joseph and Mary, who must have heard of these developments with terror. Just possibly, they had a newborn. Did those invading troops plunder Nazareth?

Varus continued his march via Samaria, stopping en route to burn Emmaus, a storm center for Athronges’s rising. When Varus entered Jerusalem, Jewish leaders managed to cast most of the blame onto extremists and agitators.

Upon this, Varus sent a part of his army into the country, to seek out those that had been the authors of the revolt; and when they were discovered, he punished some of them that were most guilty, and some he dismissed: now the number of those that were crucified on this account were two thousand.

Varus did eventually restore order, but the story has a curious series of aftermaths a decade or so later. In 6 AD, Herod Archelaus died, and in that very same year, another Judas, the Galilean, led a ferocious revolt that attempted to establish a Jewish state that was both independent and theocratic. In 9 AD, Varus led three legions into battle in Germany, where he suffered one of the worst defeats in the whole history of the Roman Empire. This is pure speculation on my part, but I wonder if as news of that defeat spread, it was the occasion for widespread (if very clandestine) celebrations across the Jewish world?

Those events had long aftermaths. Varus’s disaster effectively drew the imperial borderline in Western Europe. Meanwhile, Judas created what would become the Zealot movement, in which his family served as unofficial royalty. Two of his sons were crucified in the 40s, and another relative – a grandson? – named Menachem led the terrorist Sicarii movement in the revolt of the 60s.

Looking at these events, we understand just what the Romans were so afraid of in Jesus’s lifetime, and why they were especially nervous about rogue Galileans with religious pretensions – especially any with the slightest aspirations to kingship. And moreover, why they would be so justifiably paranoid around great feasts, such as Passover.

The crisis of 4 BC offered a prequel, a draft script, of so many of the horrors of the coming century. And that was the world into which Jesus was born.

I end with a trivia question that is, in fact, quite illuminating. In all his letters, St. Paul mentions just one contemporary monarch by name, just one emperor or king. Who was it? Well, not a Roman Caesar. It was actually the Nabatean king Aretas IV, the same who gave his precious military support to Varus in 4 BC. The same king still held power some four decades later when his representative, the ethnarch, was still in charge of Damascus, and who failed to stop the recently converted Paul from escaping the city (2 Corinthians 11). That gives an excellent sense of the short period that separated the great revolt of 4 BC from the world of Acts and the emerging Jesus Movement. The revolt happened only yesterday.

I am here adapting a column I posted at this site several years ago.