One consolation of spotty education is the opportunity to read texts later in life that you wish you had read much earlier, but which fell through the cracks until you were mature enough to appreciate them more fully.

Such was the case for me reading Gregory of Nyssa’s charming, instructive The Life of Moses, an account of the Christian life read into the Exodus story through the actions of its chief protagonist, Moses.

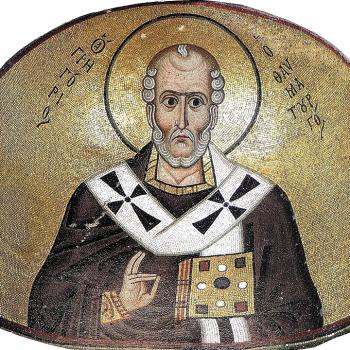

A bishop of Cappadocia (in modern-day Turkey), Gregory was the younger brother of Basil of Caesarea, who together with their friend Gregory of Nazianzus are collectively referred to as the “Cappadocian Fathers,” key shapers of and advocates for Nicene Christianity at a crucial time (the 300s) in the church’s doctrinal formation and highly revered in most traditional strands of Christianity, not least among the Eastern Orthodox.

As those steeped in early-church studies well know, allegorical or figural interpretation of the Old Testament is the coin of the realm for the church fathers, that is, the ability to read Hebrew scriptures for how they anticipate or prefigure New Testament motifs and stories and/or how they might speak directly to the joys and travails of Christian discipleship. Gregory calls this the “spiritual interpretation” or “loftier interpretation,” requiring “some subtlety of understanding and keenness of vision.”

Sometimes the “loftier” associations are apparent—say, the sacrifice of Isaac as somehow prefiguring of Christ’s atonement or Abraham and Sarah’s three visitors as an initial anticipation the Trinity—but sometimes they are not or they at least require a creative, perhaps even a whimsical theological imagination.

Take for instance the frogs among the plagues that God visits upon Egypt prior to the Jews’ departure. These “ugly and noisy amphibians” with “foul-smelling skin,” in Gregory’s eyes, represent nothing less than the evil from which we all should flee. “The breed of frogs is obviously the destructive offspring of the evil which is brought forth from the sordid heart of man,” he writes, adding that “being a man by nature and becoming a beast by passion, this kind of person [given to evil] exhibits an amphibious form of life [that is] ambiguous in nature.” The mature Christian should thus shun evil, fleeing from someone ostensibly upstanding but really “froglike and fleshy.” “And if you search the storeroom, that is to say, the secret and unmentionable things of his life,” Gregory continues, “you will discern there in his licentiousness a much greater pile of frogs.”

Gregory espies a very different allegorical meaning in the priestly vestment made for Aaron as indicated in Exodus 28:33: “On its skirts you shall make pomegranates of blue and purple and scarlet stuff, around its skirts, with bells of gold between them” (RSV).

What do the bells and pomegranates represent? Faith and conscience, of course. “The golden bells alternating with pomegranates represent the brilliance of good works,” as Gregory writes. “They are the two pursuits through which virtue is acquired, namely through faith toward the Divine and conscience toward life. . . . So let faith sound forth pure and loud in the preaching of the holy Trinity, and let life imitate the nature of a pomegranate’s fruit.”

How might one accomplish the latter, it merits asking? Gregory pounces with an answer, connecting conscience to the philosophical life devoted to truth-seeking and virtuous action. “Because it is covered with a hard and sour rind, its [the pomegranate’s] outside is inedible, but the inside is a pleasant sight with its many neatly ordered seeds, and it becomes even sweeter when it is tasted. The philosophical life, although outwardly austere and unpleasant, is yet [too] full of good hopes when it ripens. For when our Gardener opens the pomegranate of life at the proper time and manifests the hidden beauty, then . . . [all] will enjoy the sweetness.”

Additional arresting features of Gregory’s thought include his attitude toward classical learning; his insistence that, while some sure things can be known of the Divine being, God’s ultimate nature remains unfathomable from a human standpoint; and that, even so, friendship with God is superlatively desirable.

Those familiar with Augustine’s likening of classical learning to the “spoils of Egypt,” which the Israelites [i.e., the Church] could and should put to better use will find similar trains of thought in Gregory. While he recognizes that learning can result in vanity and that differences between Greek philosophy and Holy Writ abound, he nonetheless maintains that “there are certain things derived from profane education which should not be rejected when we propose to give birth to virtue. Indeed, moral and natural philosophy may become at certain times a comrade, a friend, and companion of life to the higher [i.e., Christian] way.” He itemizes geometry, astronomy, and dialectics as at once “useful” and capable of adorning the church with the “riches of reason.”

Glossing the passage in Exodus where Moses on Mount Sinai “entered the darkness and then saw God (Exodus 20:21),” Gregory wrestles with the fact the God is more often associated with light before concluding that, as with Moses, the God-searching mind “leaves behind everything that is observed, not only what sense comprehends but also what the intelligence thinks it sees.” It keeps on “penetrating deeper until by the intelligence’s yearning for understanding it gains access to the invisible and incomprehensible, and there sees God. This is the true knowledge of what is sought; [but it] is a seeing that consists of not seeing.” Or, as Gregory notes elsewhere, God ultimately resides “above comprehension,” not visible to all, but nonetheless, as truly as partially, discoverable “in the secret and ineffable areas of the intelligence” when someone honestly seeks out God.

This certain but limited knowledge in turn permits one “to be known by God and to become his friend.” Neither “servilely fearing punishment” nor a “hope for rewards, as if cashing in on the virtuous life by some businesslike . . . arrangement” should serve as the primary motivator of Christian discipleship. Rather, it is living now and everlastingly in God’s friendship. Disregarding all other things, Christians should “regard falling from God’s friendship as the only thing dreadful, and . . . consider becoming God’s friend the only thing worthy of honor and desire.”

Finally, and as should be evident by now, Gregory simply has the gift of eloquence, the capacity to outfit the spiritual, moral life with language suitable to its dignity. Experience teaches us, he says, that daily affairs life has a “restless and heaving motion.” He speaks of envy as “that congenital malady in the nature of man.” “Why do the things which happen happen?,” he guilelessly asks. Truth he sparsely, exquisitely defines as “not to have a mistaken view of Being.”

I trust my point is taken. And perhaps delay not, as I have. Whatever your age or educational status, wherever you are in the life of Christian discipleship, time is too precious not to reading Gregory’s Life of Moses. As the author himself hopes, it will lift your understanding to what is “magnificent and divine” and redound to the “common benefit in Christ Jesus.”

This essay originally appeared in Touchstone magazine (fall 2023).