The Civil War and Reconstruction continue to fascinate Americans. Recently, witness the blowback against alleged presidential candidate Nikki Haley when she refused to identify slavery as a cause of the war. Just in the past couple of months, we also note the full special issue of the Atlantic on the theme of “To Reconstruct A Nation,” or Adam Hochschild’s review essay in the New York Review of Books on how pro-Confederate sympathizers established the orthodoxy that secession and war arose from almost any cause except slavery. Today, all mainstream historians place slavery and White Supremacy absolutely centrally in the story of that conflict, to the exclusion of once popular rival themes of contention such as states’ rights, or tariffs. From this perspective, when pro-Confederates cite such alternative issues, they are consciously or otherwise creating a smoke screen to conceal the hideous truths at the heart of that Gone with the Wind mythology. Am I challenging that newer orthodoxy? Certainly not. Well, not really.

Here is my central question. If one side in a war is fighting for a specific cause, such as slavery, and the other is just as clearly not fighting over that issue, can we legitimately say that this cause was what that war was about? It’s worth debating, because that was exactly the American situation in 1861.

Put another way, I am concerned that the near-exclusive focus on slavery and White Supremacy gives the war a much higher degree of moral clarity than it deserves. It also distracts from some other matters that we should be talking about in our college classes, and in our debates over how we commemorate historical figures.

What The South Was Fighting For

The best evidence for the central role of slavery in provoking secession comes from the declarations issued by the various Southern states in 1860-61 as they justified the break. They are refreshingly frank, with none of the euphemisms found in the original US Constitution about “other persons,” when they actually meant slaves. Here is Mississippi’s document:

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the Black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.

Some of the state documents quite explicitly assert that the great national schism lay not between North and South, but rather between the slaveholding and non-slaveholding states. Nor is it difficult to find quotes from individual Confederate leaders over the next few years saying that was what the whole struggle was about, and their racial language is often very harsh.

This does not mean that slavery was foremost in the minds of everyone who supported the Confederacy, and many certainly were fighting chiefly for the states’ rights issue. You can make an excellent case that in Constitutional and legal terms alone, the Confederates had a lot of merit on their side in claiming that states had the right to secede and dissolve the union, or at least to nullify particular federal laws. Having said that, the official ideology of the Confederacy did indeed place slavery at the heart of the secessionist cause.

So, secession was about slavery and White Supremacy, QED. That is what the South was fighting for.

What The North Was Not Fighting For

The North meanwhile, the Union, must therefore have been fighting a mighty crusade against slavery and White Supremacy … Except no, it wasn’t, nothing of the sort.

Now call me a stuffy traditionalist, but I have always believed that before you can have a war, you need two (at least) sides. We know what the South fought for. What about the North? Look at all the very substantial official pronouncements and media coverage in the North in the first year or so of fighting – basically through the end of 1862. You will find certain themes and justifications mentioned time and again, and with very few exceptions, slavery is not one of them. Nor is abolition, or White Supremacy, or any cognate term. Yes, there were radical idealists and committed abolitionists in the army, like the famous Colonel Robert Gould Shaw depicted in the film Glory, but they were a minority.

What we read time and again is that the Union is fighting for national unity and sovereignty, and for national honor. This is liberal nationalism in its purest mid-nineteenth century manifestation. If there is a central ideological theme, a slogan or buzzword, it is Union itself. That word, Union, appears very frequently over the coming decade or two, as the ultimate symbol of patriotic Americanism. Just think of the Union Pacific railroad, incorporated in 1862.

It’s a famous quotation, but we should pay close attention to the words of Abraham Lincoln, in August 1862, after more than a year of war:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.

Union, Union, Union.

Why aren’t they talking about slavery? What is going on here?

Saving the Border States

In large measure, this is a practical matter. Despite initial patriotic surges on both sides of the new frontier, neither of the new American nations, North or South, was anything like as united as it would like to claim. The loyalty of several border states was difficult to predict, as the North faced secessionist rumblings from Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and even Delaware. Kentucky’s slaves represented some 21 percent of the population, very close to the figure for Tennessee and Arkansas, both of which actually did secede. Pro-Confederate factions in Missouri and Kentucky sent representatives to the Confederate Congress.

Maryland’s slave figure was lower, at thirteen percent, but secessionist ideas were strong in many parts of the state, notably in Baltimore itself. Maryland was critical, because if it withdrew from the Union, then Washington DC would find itself isolated in rebel territory, and indefensible. Hence, secessionist advocates in Maryland were suppressed with a heavy hand.

During 1861 it was an urgent priority for the Union to prevent the loss of further border regions. Even if the government had wished to come out strongly against slavery, making that a primary war aim would very probably lose at least four more states, and basically make the conduct of war impossible. Only very gingerly, after the war had been in progress for a year or two, did the administration bring abolition onto center stage, and even then, framed in terms of pragmatic military necessity.

Divisions within the Confederate states also played a role. There were plenty of Southerners who were deeply unhappy about secession, even if they themselves owned slaves. Some were driven by Jacksonian class resentment, and a real hatred of the super-wealthy Southern plantation owners. Avoiding the slavery issue raised the hope of appealing to these Southern Unionists, and persuading them either to reverse secession in their states, or else to form breakaway enclaves. Personifying that issue was Tennessee’s Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s 1864 running mate for the National Union party, and his successor as president in 1865. Johnson held slaves until mid-1863. As he famously declared, “Damn the Negroes; I am fighting these traitorous aristocrats, their masters!”

Racism, Abolitionism, and Unionism

But we should not suggest that concern about the border states alone prevented the Lincoln administration from coming out out frankly and overtly against slavery, as if this was the cause closest to their hearts. The customary narrative suggests that the North was reasonably unified, with the exception of pro-Southern traitors, “Copperheads.” But then turn to Paul D. Escott’s book The Worst Passions of Human Nature: White Supremacy in the Civil War North (University of Virginia Press, 2020). I quote the description:

Escott argues that the North’s Democratic Party was consciously and avowedly “the white man’s party,” as an extensive examination of Democratic newspapers, as well as congressional debates and other speeches by Democratic leaders, proves. The Republican Party, meanwhile, defended emancipation as a war measure but did little to attack racism or fight for equal rights. Most Republicans propagated a message that emancipation would not disturb northern race relations or the interests of northern white voters: freed slaves, it was felt, would either leave the nation or remain in the South as subordinate laborers.

Now, belief in White Supremacy did not necessarily mean support for slavery, but it obviously did not signal any willingness to go off to war to fight for the rights of enslaved Black people. To say the least, Escott’s findings do not suggest any great appetite for a crusade against slavery in 1861, or indeed, at any time. When the demands of war and conscription became too great, ordinary citizens were happy to rebel, and to turn their anger against freed Blacks, as occurred notoriously in New York City in 1863. This was not all the work of some lunatic Copperhead minority.

Actually, those known public manifestations of racist and pro-slavery sentiment give only a poor idea of popular attitudes in the North. The Union government ran a highly repressive apparatus of policing and censorship that came down very hard on any suspected disloyalty. See for instance the harrowing accounts in William A. Blair, With Malice Toward Some: Treason and Loyalty in the Civil War Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2014). If the media had been freer, we would have a still clearer sense of the extent of White Supremacist attitudes in the North.

From this perspective, we get a better sense of why Lincoln seemed so half-hearted about abolitionism, as opposed to national Union at all costs: he knew his electorate. Paul Escott’s book makes an excellent case that if Lincoln had survived the war, he would have presided over a Reconstruction even less sympathetic to Black interests than the policies that got Andrew Johnson impeached.

Over and above Lincoln, take these words from Ulysses S. Grant, in August 1862:

I never was an abolitionist, not even what could be called antislavery; but I try to judge fairly and honestly; and it became patent to my mind, early in the rebellion, that the North and South could never live at peace with each other except as one nation, and that without slavery.

John Reeves has a major new book titled Soldier of Destiny: Slavery, Secession, and the Redemption of Ulysses S. Grant, and I quote from Harold Holzer’s Wall Street Journal review:

Re-enlisting at the outset of the Civil War, however, Grant still hoped to “whip the rebellion,” as he wrote, while “preserving all constitutional rights”—meaning the right of whites (like his wife and father-in-law) to own blacks. … At this point, Grant opposed abolition as fiercely as he condemned secession but understood from the outset: “If it is necessary that slavery should fall that the Republic may continue its existence, let slavery go.”

A World of Honor

Any federal appeal to the cause of abolition or racial justice would have been suicidally counter-productive in 1861. But there were things for which Americans of the time, North and South, were prepared to fight and die.

When we read contemporary statements about the war, North and South, there is one theme, one idea, that inflames both sides in 1861, and that is Honor. Lacking any sense of the underlying ideology, later historians skim over such rhetoric as empty verbiage, but in so doing, they miss the heart of the story. For nineteenth century Americans, honor was the critical value underlying civilized society, and honor was the most cherished possession of a person, a family, or a community. Honor was intimately linked to good reputation, which must be defended at all costs, and violence easily erupted in a society deeply sensitive to personal slights. Those ideas were fundamentally linked to notions of masculinity, of proper manhood, but concepts of honor and reputation absolutely shaped the proper behavior expected of both sexes.

These ideas were famously analyzed in Bertram Wyatt-Brown’s 1982 book Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (Oxford University Press), but they ran well beyond the South strictly defined. The American obsession with honor and shame, insult and retaliation, fascinated and horrified European visitors, and it is a centerpiece of Charles Dickens’s Martin Chuzzlewit (1842). Dickens was very accustomed to such ideas in Britain, where they were the preserve of aristocratic elites – what we might call upper class twits, of the kind he despised. What appalled him in America was how such ideas and language had been democratized to become a popular ideology, expressed by every farmer and teenaged clerk. Defense of honor and family drove the country’s many duels and personal feuds and vendettas, some of which amounted to minor wars.

Let me return here to a theme I discussed at length in a blogpost at this site some years ago, on “the Long Civil War.” I once had a Penn State colleague named Bill Pencak, a fine historian who more or less denied the existence of the Civil War. That sounds like revisionism run amok, until you realize his tongue-in-cheek intent. What he argued, provocatively, was that America between (say) 1835 and 1875 was rife with endemic local wars and conflicts, night-riding and massacre, by urban riots and lynchings, by acts of mass community vigilantism and justice, by the mass murder of minorities and ethnic outsiders. This occurred to an extent inconceivable in contemporary Europe. Moreover, that was true in all sections of the nation. As a matter of convenience, said Pencak, we happen to take the four most spectacularly bloody years of this ongoing carnage and label them “The Civil War.” Those years differed in severity from what went on before or since, but not in kind.

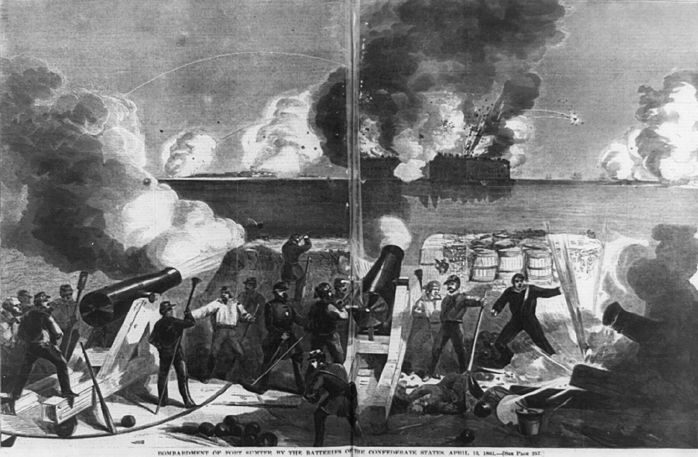

So, what happened in 1860 and 1861? The South saw in Lincoln’s Republicans a massive threat to its economic survival, but also to the honor and reputation of its states, cities, and families. Only armed force could correct the insult. Northerners enlisted in their tens of thousands to avenge the insult to the national flag at Fort Sumter, and the searing violation of national honor. Hard though it might be today to reconstruct those passions, the firing on the flag aroused a national fury comparable to the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. As the North mobilized for war, we hear far more in speeches and newspapers about that sacred Fort Sumter flag than we ever do about slavery.

To a degree that might surprise us today, Americans at the time were nervous about awarding medals to soldiers and sailors, as they smacked too much of European monarchy and pageantry. But in 1861, the Union did decide to reward exceptional service with a new distinction called – what else? – the Medal of Honor.

So What Was The Civil War About?

To reiterate my earlier statement: Could the Civil War have happened without the slavery issue? Definitely and unarguably not. Or to expand that, could the Confederacy have come into being without the slavery issue? Just as definitely not.

But at the same time, the Union that went to war in 1861 was just as clearly not fighting over slavery. To draw a crucial distinction, the North was fighting an enemy that was a slave society dedicated to White Supremacy; but it was not fighting that foe because it was a slave society dedicated to White Supremacy.

Only very gradually did slavery- and race-related issues achieve any prominence in the federal cause. Among other things, that relative unimportance goes far towards explain the failure of Reconstruction. Radical Republicans believed they could maintain a solid public opinion in the North to maintain the kind of long-haul policies needed to enforce that regime, and they just did not have that luxury.

If you are teaching a class on the civil war, always put the slavery issue absolutely front and center in the narrative. But never suggest that this was the topic that directly or solely motivated the side that eventually triumphed in the struggle.