I have been reading Matthew Barrett’s The Reformation as Renewal: Retrieving the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church in preparation for a review. There is much that is commendable in this book, and when my full review is published, likely this summer, I will provide a link for any interested readers. In the abstract, I am for strengthening the connective tissue between the medieval Christianity and the Reformation, so I welcome these sorts of projects. For today, however, I want to use Barrett’s text to address a broader gripe I have with some strands of evangelical historiography and the Reformation.

I have been reading Matthew Barrett’s The Reformation as Renewal: Retrieving the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church in preparation for a review. There is much that is commendable in this book, and when my full review is published, likely this summer, I will provide a link for any interested readers. In the abstract, I am for strengthening the connective tissue between the medieval Christianity and the Reformation, so I welcome these sorts of projects. For today, however, I want to use Barrett’s text to address a broader gripe I have with some strands of evangelical historiography and the Reformation.

In short, Barrett’s big idea is to claim that Luther, Calvin, Zwingli and their Protestant progeny never set out to begin a new church movement. Rather, they linked their reform efforts to a project of realigning the Western Church with its ancient and high medieval forebears. Tracing a line from Augustine to Thomas Aquinas through Anselm and others, Barrett links catholicity to a particular brand of Christian Platonism that, he argues, the major reformers all subscribed to in one way or another, knowingly or otherwise.

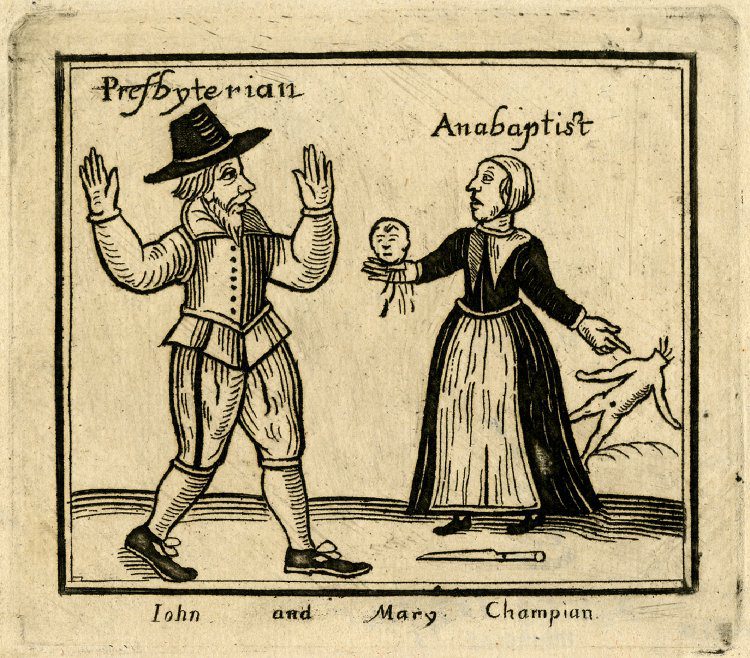

There are heroes and villains in these sorts of accounts. For evangelical scholars eager to shore up their theological bona fides, too often the so-called radicals of the Reformation are made easy targets. These Anabaptists and Spiritualists are pitted against Wittenberg and Geneva, as well as Rome, as indicators of what Luther and Calvin were not trying to do—sever the Christian community from the patristic and medieval cloud of witnesses. The title of Barrett’s chapter on Anabaptism, “Abandoning Catholicity for Primitive Christianity,” captures his assertion boldly. “While the Reformers sought to reform the one church,” Barrett writes, “the radicals decided to abandon the one church and were not shy in their partial and sometimes total rejection of its catholic tradition.” And again: “The Reformers believed they were renewing Christendom itself, but the radicals spit on the history of Christendom and made the most extreme claim possible: to restore primitive Christianity, Christendom must be abandoned.”

Barrett shows his confessional hand more than most in his treatment of the Reformation radicals. But his summation is indicative of a larger push to oust the “Reformers’ stepchildren,” to borrow Leonard Verduin’s nomenclature. Early 20th century Dutch theologian Herman Bavinck had it out for the Anabaptists, labeling them heretics who smelled sort of like the Reformation, but veered away from the essence of true Christianity. More recently, Craig Carter associated Anabaptism with “irrational mysticism that opposes reason” and that rejected true catholicity (by rejecting scholasticism—by which Carter means a certain kind of scholasticism). Peter Sammons, an evangelical Thomist, also claims Luther and Calvin “built their ministries upon the truths articulated at Chalcedon and Nicaea” and “wrote catechisms and confessions for their people, seeing the anti-confessionalism of the radical Anabaptists as anti-Christian.” Arthur Kay recently characterized the Anabaptist way as a “just-me-and-my-Bible approach where the Scriptures are interpreted in isolation from history and tradition.” The punching bag is well-marked by Reformed gloves. You get the picture.

But is it an accurate picture? Is it right to say that radicals had no desire to align themselves with the ancients, no patience for the things that had come before, no awareness of the need for catholicity? On the other hand, is it true that Luther, Calvin, and others saw themselves as standard bearers for the Great Tradition, that they meticulously and self-consciously aligned their ideas to fit the mold of the great Fathers and doctors of a glorious scholastic Christendom? The answer is—as with all history worth its salt—it’s complicated.

For the purposes of this piece, I’ll touch briefly on the second question by focusing my efforts on the first question, were Anabaptists anti-tradition? And I’ll give you my answer up front: It depends on what the tradition was, who was writing, and why. But here’s the rub: this is true not only of Anabaptists, but of all the Protestant reformers.

The reformers’ use of ancient sources was often imbalanced and ad hoc. Early Protestants were walking a tightrope in their attempts to secure the stability of their various movements. On the one hand, they needed to prove that the medieval view of the church and its piety they inherited was dangerous enough to prompt self-removal. On the other hand, they also needed to prove that they were not the heretics or schismatics that the secular authorities suspected them of being. This was as true for so-called radicals as it was for Lutherans and Reformed Christians. Appeals to and against traditional authorities were polemical in most cases, sources one could accumulate to marshal a defense for one’s perspective. This is not to say that the reformers didn’t genuinely care what church fathers or medieval doctors wrote (although it’s clear they weren’t always careful in their assessment). But the fact of the matter is that the early reformers frequently used tradition to bolster their (often idiosyncratic) interpretations of scripture. The respect given to the church fathers as a collective voice masked the manifold ways individual voices could be deployed for various reasons. And when Protestants wanted to get spicy, they had no issue pointing that out (see, e.g., Luther’s “On the Councils and the Church”). But many Anabaptists and Spiritualists were, like Lutherans and Calvinists, aware they’d be more confident bringing tradition as a wingman to the doctrinal dance.

We know, for instance, that Tertullian’s writings significantly influenced Conrad Grebel in Zürich, thanks to a 1521 edition of his writings compiled by Beatus Rhenanus. (See Andy Alexis-Baker’s articles in MQR and Perichoresis where he has aptly analyzed Anabaptist use of patristic sources.) Grebel, eager in his reading, once confidently teased his brother-in-law, Vadian, that he better watch out, “lest I make you a Tertullian!” But Tertullian was more than a pleasure read for Grebel and others. The language for baptism that coalesced within the Swiss Anabaptist group emphasized the sacramentum as military pledge, and this was taken directly from Tertullian and possibly others, like John Chrysostom. By affirming the pledging act of baptism, some Anabaptists self-consciously placed themselves in a line with the ancient sources, as the metaphor appeared frequently before the militant emphasis was transposed from baptism and onto the sacrament of confirmation in the twelfth century. (I’m writing a book on Anabaptists and medieval chivalry, so you’ll hear more on this later.)

Balthasar Hubmaier deployed the Church Fathers to support his view of baptism. He also developed one of the first if not the first Protestant catechism on Christian faith, using the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the Ten Commandments as the framework. Hubmaier was easily one of the most well-educated of the early Anabaptists, having received a doctorate in theology from the University of Ingolstadt under the guidance of Johannes Eck. His polemical pen was as sharp as his mind, and he often set the tip of that pen toward defending believer’s baptism and decrying the abuses of the papal hierarchy. Like Luther and Calvin, Hubmaier was amenable to using the Church Fathers inasmuch as their view supported what Hubmaier believed to be the true teaching of scripture. In his Old and New Teachers on Baptism, he marshaled the voices of Eusebius, Cyril, Origen, Chrysostom, and Jerome to support his reading of the Bible.

Or consider Pilgram Marpeck. Evidence of medieval influence is clear in Marpeck’s writings, especially in his allegorical treatment of the bridal chamber, echoing Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons on the Song of Songs. But I want to single out his treatment of the descensus ad infernos from the Apostles’ Creed. His thoughts come up in a preface to his “Explanation of the Testaments” (c. 1545), wherein he critiques a view that Old Testament Israelites received the benefits of Christ’s redemption prior to his incarnation. He says such an opinion “would be a denial of the common Christian article of faith which says [Christ] ‘descended into hell.’” What good would this confession be if Old Testament believers were Christians? Moreover, he says,

“what would happen to the faith of the ancient teachers and many others with them who on their understanding of the witness of holy apostolic Scripture have believed and still believe the article about the descent of Christ to hell and that actual redemption took place through him today? Such an opinion would become an error and become known as a special sect.”

Marpeck’s rhetorical bafflement implies the view that his community confesses the ancient faith, spoken in Scripture and elucidated by the ancient teachers. And they do not confess alone, but with many others.

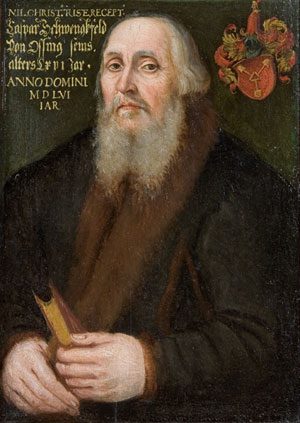

To bring my point home clearly, let’s examine a confessional statement from Caspar Schwenckfeld, one of the most maligned figures in the magisterial reformers’ imaginations. Schwenckfeld was no Anabaptist, and his theology was the subject of controversy, particularly over his moratorium on the sacraments and the nature of Christ’s “flesh” in the incarnation and in the Supper. He was exiled from Silesia in 1540, and in 1545 he wrote a “Confession of the Beliefs of Caspar Schwenckfeld,” likely in part to ingratiate himself with the local nobility. The piece is highly personal, stating at the outset that “I hold to and confess the twelve common articles of our Christian belief as I myself learned them from my mother or parents as a young boy, and as it also was stated for me at my baptism.” Shortly thereafter, he continues:

“In addition to this, I believe all that the holy Christian church and the ancient councils affirm. Such things are the certified received teachings of the Christian church with the witness of Holy Scripture from God and to the Lord Jesus Christ.”

As if to clarify this point, he concludes: “Therefore I believe in a holy Christian baptism for the washing away of sins in the confession of the Holy Trinity and calling upon the name of the Lord. And I am not an Anabaptist or a sectarian, but I hope a baptized, though weak Christian.”

There is a dizzying diversity of views and approaches in this variegated movement historians have deemed the “Radical Reformation.” Certainly there were many who did away altogether with the idea of a universal church outside their own small community. Certainly many Anabaptists were turned off by the prospect of Christendom, if by that we mean the codependency of the mayor and the pastor, or religious purity guaranteed at the tip of a sword—a sword whose business end was usually pointed in their direction. But many saw a likeness of themselves in the portraits of the Fathers given to them by their universities, their former monasteries, and especially their collective reading of newly available sources (thank you, printing press!).

My aim in rehearsing these few examples above is not to prove the catholicity of Anabaptists or Spiritualists. Catholicity itself is a moving target in these confessional debates. Nor is it to assert Anabaptists interpreted the Fathers, or even scripture, correctly. The purpose of this essay is simply twofold.

1) I think it’s worthwhile challenge some of the confessional presuppositions that creep into history when we let our heroes investigate the matter for us. The magisterial reformers earned their plot with much sweat and anguish. They could be pretty jumpy, and rightfully so. This led them to paint with broad strokes, especially when it came to coloring their enemies. Anabaptist for them conjured up the most fantastic misanthrope, the most scandalous anarchy. Reformers’ biases, in some cases, masked their similarities (think naive Anabaptist biblicism vs. magisterial regulative principle). When we take the PR of Calvin and Luther at face value, it is easy to dismiss Anabaptists as wild-eyed iconoclasts of both physical space and theological heritage. In the end, that is all these people became to the magisterial Reformers—simultaneously a nuisance and a foil to contrast their own supposed reasonability and catholicity. But historians do not simply repeat the narrative; we complicate the narrative, because human beings are complicated.

2) Comparing Roman, magisterial, and radical uses of tradition clarifies the ways in which tradition was not simply received, it was constructed to certain ends. In this way, the reformers were all quite catholic indeed! Luther, Calvin, Marpeck, Bellarmine, and a host of others across the confessional spectrum saw the value, to varying degrees, in conscripting ancient authors, in large part because it gave them rhetorical ammunition. This is not to say that church leaders never changed their minds because of a reading of Augustine, Origen, or Thomas. Certainly they did in many cases. However, in polemical contests, both against Rome and against one another, Reformers weren’t learning with the church so much as borrowing the church’s muscle. Esther Chung-Kim’s study, Inventing Authority, is instructive here. As she says it better than I ever could, I will appeal to her authority and give her the final word (see what I did there?):

2) Comparing Roman, magisterial, and radical uses of tradition clarifies the ways in which tradition was not simply received, it was constructed to certain ends. In this way, the reformers were all quite catholic indeed! Luther, Calvin, Marpeck, Bellarmine, and a host of others across the confessional spectrum saw the value, to varying degrees, in conscripting ancient authors, in large part because it gave them rhetorical ammunition. This is not to say that church leaders never changed their minds because of a reading of Augustine, Origen, or Thomas. Certainly they did in many cases. However, in polemical contests, both against Rome and against one another, Reformers weren’t learning with the church so much as borrowing the church’s muscle. Esther Chung-Kim’s study, Inventing Authority, is instructive here. As she says it better than I ever could, I will appeal to her authority and give her the final word (see what I did there?):

“By interpreting the ancient tradition as the heritage of the Protestants, the reformers created a ‘new’ ancient tradition. With this reinterpretation, they claimed to be legitimate heirs of the early church and faithful interpreters of God’s word. Perhaps by creating multiple Christian traditions that all claimed to stem from the early church, the reformers genuinely inherited the spirit of theological diversity of the early church itself.”