“You should always be proud of being an Indian. But never tell anyone.” This was essentially all my father told me about our Native heritage. Later, he would tell me a bit about his mother dying and made sure my siblings and I were recognized as citizens of the Chickasaw Nation. I only ever saw one picture of my grandmother until I was in college. Everything else I would learn about my Native American story would be largely without my dad’s help. I tell you this because of the strange similarities and differences between my own story and that of Elizabeth Hoover, who the New Yorker recently profiled. Hoover is a tenured professor of environmental science, policy and management at the University of California, Berkley who was recently outed for having lied about being part of Native American communities. She received her doctorate from Brown and her bachelor’s at Williams College. At both institutions, she claimed to be both Mohawk and Mi’kmaq. The New Yorker piece left me dissatisfied for a few reasons, and made me want to tell a different story of this process, my own.

The phenomenon of “passing” or living as a different identity than whatever one was born as has been incredibly common across history. Even in the last fifty years, a New York Times film critic lived as a white man despite having been born to a black parent in Louisiana, and an award winning “Afro-Cuban” novelist hid behind this assumed identity, keeping the truth from even his partner. This practice has almost always been in the direction of racialized minority passing as white. It is only in the last few years that we have seen white people present themselves as racialized minorities. Why? The same reason the reverse happened for so long: one believes life will be easier this way. The term “pretendian” has come to be a catch-all for non-Natives who lie or fake about their lives and connections to Indigenous communities. Perhaps the most famous examples are Senator Elizabeth Warren and Andrea Smith, an anthropologist who taught for many years at UC-Riverside and other universities. This mode of falsehood has become particularly popular in the realms of politics and the academy.

Now one might ask, what harm does this behavior cause? In a very real sense, at least in the academic context, it is theft. Similar to the many ways in which land was stolen from Native nations, now our very identity is being picked up as a final insult added to the plethora of injuries endured. Elizabeth Hoover won grants and fellowships aimed towards supporting minority grand students and faculty. Those funds might have gone to help those they were intended for. Hoover has promised to devote all royalties from her books to unnamed Native charities. Unfortunately, academic books rarely make money, especially after they’ve been out for a few years. This then seems to be merely an appeal sympathy by appearing to make a sacrifice. She is not stepping down from her professorship or making any other steps to make recompense.

Since childhood, I have been a library hound. I routinely checked out as many books as my library card would allow. As soon as I learned how to read, I check out every book I could find about our tribe. It wasn’t long though before I stopped. I realized rather quickly that the children’s books I was reading all told the same information with slightly different sentences and illustrations. After I had read one, none of them taught me anything new. In the late 90s and early 00s, this was the best I could do in my small town. Additionally, I was homeschooled. I forget most people (if they still played the game) still wanted to be the cowboy instead of the Indian. Most kids didn’t check out the strange books of “Indian crafts” as an early attempt at cultural reconnection.

Now, it can be granted that much of what I’m going to tell you is due exclusively to my own anxiety; however, I was terrified of being a pretendian. I had seen on Twitter (back when it was called that) how fakers were rightly pilloried by the Indigenous community. And despite having had tribal citizenship since I was twelve, I wondered, what if it all came back a lie? I didn’t want to be one of these people who lied to the whole world. But I had grown up in the South, and everyone saw me as white. One might even say I “passed” as white. By most nineteenth century standards, I would still be considered an Indian. When I went to college, things changed a bit. In my first week of school, I was asked at least a dozen times in settings of various seriousness about my racial background. My roommate asked if I was Greek. During move-in someone asked if I was half-Asian. One of my RAs thought I was Latino. I explained to each of them that I was part Native, but otherwise of European ancestry.

This inevitably brought up a question. “How Indian are you?” I can barely count the number of times I’ve been asked this question. My answer varies on how much I trust and like the person inquiring. It can be one word—”enough.” Or, it can be a twenty-minute explanation of the cultural and governmental complexities of the question with a side dish of my own anxieties. There is no simple answer. According to the Chickasaw Nation, I am simply a citizen like any other living outside the bounds of our nation in Southern Oklahoma. The United States government tells me according to my Certified Degree of Indian Blood card that I am 3/32 Indian.[1] My white grandmother had a DNA test done, and it tells me that according to their notoriously inconclusive databanks I am around 12 percent Native. Which of these answers is most helpful?

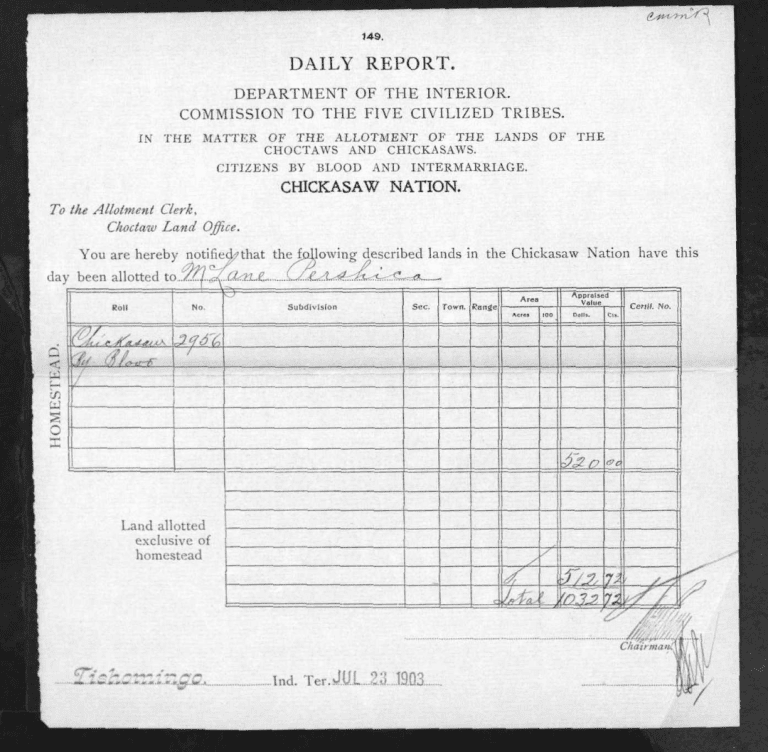

Well, all of them and none, depending what questions we are really asking. I can trace my ancestry directly back to someone, McLane Pershika, who was on the Dawe’s Rolls created by the Curtis Act of 1898. This act was part of the process of breaking up tribal nations in the attempt to force assimilation. Indigenous political organization could not be recognized because that would imply sovereignty over the land as every treaty between the United States and Native nations had. But this act did allow that every head of household would be granted a portion of land, instead of simply stealing all of it, and only the “excess” would be sold to whites. Now, only five generations later, my siblings and I own land passed down to us after our great-grandmother’s death. Again, much of this should have allayed my fears.

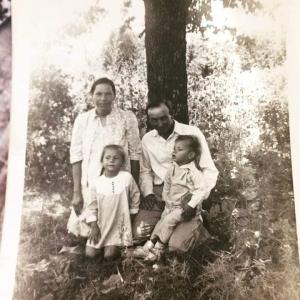

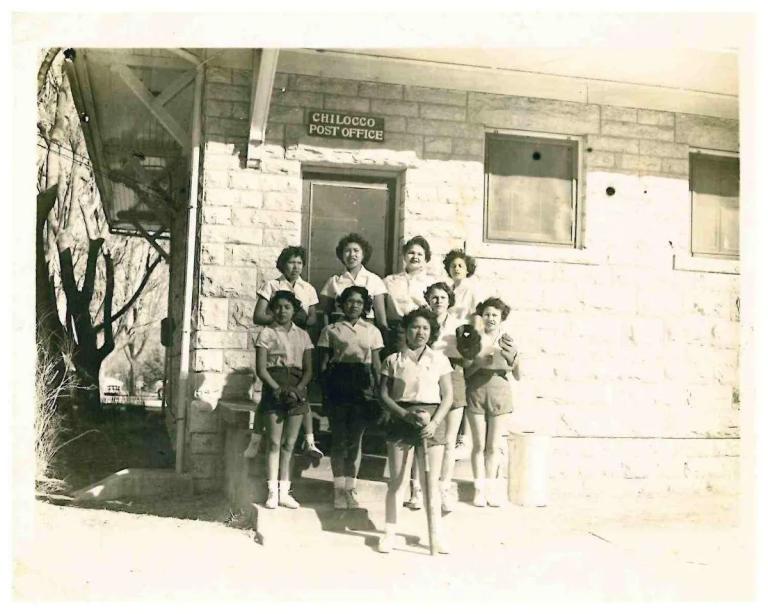

When I was a sophomore in college, my father died unexpectedly. There’s a lot I don’t remember from the weeks surrounding his death. It was a time of utter chaos. One moment sticks out in my mind though. My great-uncle B.F. came to the funeral from Oklahoma, and he took the opportunity to explain a lot of my grandmother’s story and our larger family. The day after the funeral, essentially everyone had left. But he and I and my mom sat in our living room. Both Hoover’s and my story center on a heroic grandmother. Hoover’s ancestor allegedly killed herself. The ways in which this plays into several tropes of the “Indian princess” is both problematic and something which I don’t have time to cover. My own grandmother was one of the first women in our tribe to graduate with a two-year nursing degree after her time at the Chilocco Indian School. She was also in the first generation of Natives to be born with United States citizenship. After hearing this and many other stories, I and my siblings in our ways started sifting through them with the assistance of the internet and extended family. One day, my brother sent me a picture. It was my grandmother’s basketball team from boarding school with the school’s name proudly emblazoned above them. I felt something strange looking at that picture. I feel it even now as I’m writing this. For some reason, that photo makes it all real to me.

So why am I telling you all of this? For starters, it helps show how ridiculous Hoover’s story is. If family stories have a basis in reality and history, they can always be hunted down. Even if the search ends in records destroyed or lost to fire, it could be continued through reaching out the communities she claimed to be a part of. Part of why this matters is because Native American nations are a political rather than an ethnic minority. The nature of Native American communities as political realities means that even if she wasn’t Native, she could have become close with and even adopted into these communities. We are recognized as sovereign Nations by the Constitution and innumerable treaties. As Justice Neil Gorsuch has noted, just because the law has been ignored for generations does not mean it ceases to be the law.

My doctoral advisor and I were discussing Hoover’s story recently, and he commented that he cut his long hair when he left to start graduate school because he was concerned about being pigeon-holed as the Native kid. Contrast this with Hoover, who was described in the New Yorker by one of my professors (who happens to be from the same Mohawk community which Hoover also claimed) as “like an Etsy store had exploded over her.” Hoover took advantage of how White people perceive Natives—as an ossified, primitive culture, based in “beads and feathers” as Vine Deloria would put it. She used their preconceived notions of Indigenous identity for her own gain. Meanwhile, actual Native Americans like my advisor worried about how they might be viewed if they in any way appeared Indigenous. As one of Hoover’s former colleagues put it in the New Yorker piece, “She got grants, and she got fellowships, and she checked boxes, and she got positions… And so she exploited the system. But I think the system also was very happy to have her as the visible Native.”

Since this crisis has become more public (I first heard about it on Native Twitter in 2019), I have often thought about how Hoover and others might have handled the situation differently or salvaged some sense of intellectual honesty. In considering this, my mind returns again and again to the final class meeting of my African American Political Thought seminar, where I had the privilege to study under Cornel West. He told us “Every moment is an opportunity to act out of courage and to redeem oneself from cowardice.” Hoover had that chance every day, at least since she was an undergraduate. And every day, she chose cowardice.

[1] Another problem related to passing is that any Native person who could pass for white did so whenever they could. Census takers took their word for it. Family lore tells us that several of our ancestors did this and for very understandable reasons.