I have heard the name Wendell Berry for years, but I have never made the time to read one of his books, either his essays or novels. Upon listening to the excellent podcast The Scandal of Reading about Berry’s novel Jayber Crow, I finally settled on reading it. It is a busy time of the semester, but I am really trying to make space in my schedule to read fiction.

At the beginning of the story, there is a particular passage about time and history that grabbed my attention especially with some of the changes happening in my family. The protagonist (Jayber is a small town barber) reflects on how time is different for the young and the old: “Back there at the beginning, as I see now, my life was all time and almost no memory….And now, nearing the end, I see that my life is almost entirely memory and very little time.”

As a history professor, my job is to narrate memories. It is a selective process we learn from our teachers or what our own memories deem important. Historical distance often softens the blow of our memories especially the painful ones. The busyness of time has the duty to distract us from the reality that we will one day become just memories. What about the memories of the past that do not make it in the history books? What happens when these questions relate to our loved ones? Will they just vanish like the forgotten ones in the movie Coco? Moreover, how can books help us think about some of these questions?

The reason I have been thinking more about these questions is that my father finally retired from his job. He has been a foreman at a cams manufacturer for over fifty years. The shop was down the street from where we lived. It was also my first job. He is now a few years shy of eighty. My father’s consistent weekly routine has been a model for me, yet it is not the weekly labor at the shop that defined him. The fact that he made space for reading in his daily life probably made its biggest impact on me. In fact, my dad’s routine of reading the Bible, biblical commentaries, and theology books eventually opened the door to being a pastor. He eventually had two jobs for decades. Where did he find the energy? But more importantly for this essay, where did he find the time to read daily?

I had the opportunity to travel to Costa Rica with my father six years ago. There were many things I discovered on this trip, which I have written about elsewhere, especially my father’s love of Augustine (this is also a fifty-plus year love affair). For instance, my dad shared with me that he was present when John F. Kennedy visited San José, yet hearing about it from a tour guide was an added bonus (I am hoping to write a little more about Costa Rica in future posts, but this essay and my previous work provides some highlights).

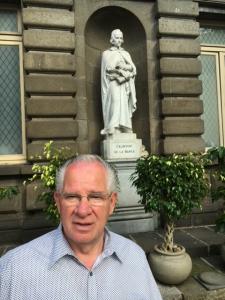

The highlight of my trip was the tour of the National Theater of Costa Rica in San José. I took the opportunity to take pictures of the busts of the national writers of modern Costa Rica and began learning about authors like Eunice Odio, Yolanda Oreamuno, and Joaquín Gutiérrez (one of my long term plans is to translate Oreamuno into English). My father did not recall much about these writers, but it was another statue that caught his attention: the statue of sixteenth-century Spanish poet Pedro Calderón de la Barca.

Calderón’s Life is a Dream was one of the first fictional books (and non-Augustine books) that I saw excitement in my father’s eyes (so much so that I asked him to pose with the statue). It really surprised me because his reading of choice is almost exclusively theology books now. Reading the Bible is what gives him the most joy, and then theology books. That has been the case for years. What was it about Calderón’s play that brought back happy memories?

I recently decided to finally read the play myself and thoroughly enjoyed it, but what really stood out to me was the way Calderón is a legend in the Spanish-speaking world, whereas I have never heard of him until seeing his statue in San José, Costa Rica. Why the disconnect? Part of this has to do with the way we learn literature and history in the United States, and the lack of even trying to know anything about Latin American culture even though we have all been neighbors for quite awhile. I have been lately obsessed with the history of what people read, both the classics and contemporary works, especially since I have noticed the declining rate of familiarity with good books among my students. I have tried to correct this a bit with my sons by following Jessica Hooten Wilson’s list of good books in her book Reading for the Love of God.

Often what is missing from these conversations about reading habits is what are U.S. Latino/as and Latin Americans reading (again, more on this in future posts). Do they also have an interest in both the classics and contemporary literature? There are clearly Latin American literary trends: Borges, magical realism, Bolaño, and contemporary Latina horror to name a few. My father is clearly a reader of the classics, but his reading habits bring up another issue.

Zena Hitz points out in her book Lost in Thought that the pleasures of the intellectual life that comes from reading is not something limited to scholars or their students. In fact, after a hard day at work, what is more human than relaxing with a good book before bedtime? What made this even more vivid was one of Hitz’s favorite subjects in the book is Augustine (128-48). Augustine has been a constant companion as early as I can remember since my father seems to always read him. Hitz closes her book with this thought: “If intellectual life is not an elite property but a piece of the human heritage, it belongs first and fundamentally to ordinary human beings” (203). Hitz illuminates what I saw modeled by my father and now myself.

Diving into Jayber Crow at the start of another semester may not have been the smartest move, but making space for good literature is my little attempt to make time to escape into an imaginative world, one that highlights the beauty of human community. Reading books is not just something to do because of leisure, but a crucial element that makes us feel more human. Hitz writes: “Good fiction resonates in truth; good history tells affecting stories. So too, literary images inspire real-life models, and vice versa. Our lives are responsive to books; books in turn reflect our lives” (49). It seems silly to have to write about the case for reading, joining in the chorus of other writers who care about great books, but the autobiographical aspect of this essay revealed to me that traveling to my father’s country years later, of all the things to focus on ends up being what he was reading (and who are the great Costa Rican writers).

I hope my father has many years of a happy life ahead of him. In a few weeks he will be traveling back to Costa Rica with my oldest son. He has actually started his retirement teaching him Spanish, and I am hoping both my sons will be bilingual unlike myself who at best struggles with Spanglish. One thing is sure about the rest of all our lives is that it will be surrounded by books (of course, Augustine’s books will be among them).