Los Reyes Magos, ca. 1875-1900, carved and painted wood with metal and string. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection

Los Reyes Magos, ca. 1875-1900, carved and painted wood with metal and string. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection

CASPAR: I have been looking around for quite a while. I no longer see the wonderous star, our wonderous guide, that has been leading us the whole time. What I really think, what I reckon, is that we have reached the place where the wonderous child whom we are seeking was born. Truly indeed, here is the great altepetl of Jerusalem. I think that we have now found what we are seeking. But come, our servant. Go forth, enter the altepetl of Jerusalem. Tell him, explain to him, that we came from the east and that we kiss his hands, his feet, four hundred times. May he give us his royal authorization so that we can go put before him what our problem is. And here on the plain of his great altepetl of Jerusalem, here we await his royal authorization so that we can go there, we can go put before him what our problem is.

MESSENGER: Let me carry out your royal command, let me do what you command me, since I am your servant. (The messenger goes to Herod’s door….)

Thus begins the Nahuatl-language play, “The Three Kings,” a catechistic drama produced in colonial Mexico. Co-authored by classically-educated tri-lingual Nahua scholars (Nahuatl, Castilian, Latin) and their Franciscan teachers, these dramas Nahuatlilized the European tradition of vernacular medieval drama even as they drew upon the Mesoamerican tradition of poetry and performance. Earlier this week, students and I did a table read of “Three Kings” from Nahuatl Theater, Volume 1: Death and Life in Colonial Nahua Mexico (ed. Barry Sell and Louise M. Burkhart). I’d like to share our discussion.

Medieval Vernacular Drama

Franciscans and Dominicans introduced vernacular Christian plays during the rise of medieval towns. Using local languages ensured that even the illiterate could learn from these didactic, yet entertaining performances meant to imprint the faith in one’s memory and heart. Religious theater might be staged all over town and end inside the church, drawing townspeople along and perhaps including Mass. Plays focused on Scripture, virtues and vices, the lives of saints, and miracles.

Outdoor Medieval Religious Drama

Vernacular Drama in Colonial Mexico

Among the pre-contact Nahuas, traditional religious activities focused more on collective rituals than on preaching or private devotion. Nahuas gathered for evening recitations and performances of pictorial texts, which functioned as storyboards; accompanied by music, poets would recite as actors performed. Nahuatl Christian theater thus blended with a pre-existing tradition; as Daniel Mosquera points out in his introductory essay, “Nahuatl Catechistic Drama: New Translations, Old Preoccupations,” “we can surmise a remarkable growing devotion that owed as much to the language’s ability to transmit powerful emotions as to the natives’ adherence to signs that verified some sense of continuity” (64). Though some Nahuas composed plays, most were penned by Franciscan friars assisted by Nahua aides. [Various Church Councils in Spain and New Spain affected performance of religious drama, but I’ll save that for another post.]

Pre-contact Nahua Performance, Florentine Codex

“The Three Kings” adheres to what Mosquera identifies as one of the main didactic goals of catechistic drama: “to transport the natives back to a mythical origin, in this case biblical, the backdrop against which social, moral, and sacramental notions were implemented” (61). Students and I were fascinated by the embedded catechesis, especially the decision to have the three rulers tell the precious child about his future sacrifice and death when they meet him in the altepetl of Bethlehem. These speeches are not in Scripture.

Summary (in italics) and Comments:

Three rulers from where the sun comes out arrive on horseback to the altepetl of Jerusalem and send their messenger to Herod’s steward to request an audience so that they may kiss his hands and feet. Herod greets them in the elevated Nahuatl speech reserved for elites.

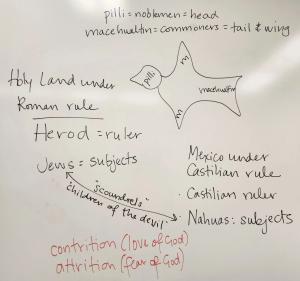

The rulers from the east are tlatoque, plural of tlatoani, i.e., Great Speaker or dynastic ruler, and arrive on horseback to an altepetl (largest socio-political unit to survive colonization), much as Castilians arrived on horseback from the east. Horses, of course, had gone extinct in the Americas prior to European arrival so Nahuas initially called them “deer;” they thus represented foreign beasts brought from the east. Kissing hands was a European tradition of greeting; kissing hands and feet was a Mesoamerican tradition. Editor Barry Sell notes that Herod’s use of pre-contact forms of elevated speech mark him as a vile character lower in status than the visiting rulers. The Nahua audience would have recognized this immediately.

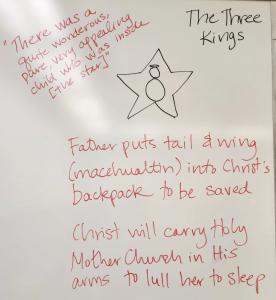

Melchior discloses a prophecy about a star; 12 elders watched from a mountaintop for 1600 years until He by Whom All Live (ipalnemohualoni), The Lord of the Near, the Lord of the Nigh (in tloque in nahuaque) showed them a star with “a quite wonderous, pure, very appealing child inside of it” (125).

The number twelve references both the Apostles and the Franciscans who arrived to New Spain in 1524, known as “The Twelve.” Nahuas had a traditional counting system based on 20, so 1600 = 4 x (20 x 20). The two Nahuatl names are pre-contact expressions applied to the Christian God. I’m not sure why the rulers see a child in the star.

Waking Caspar and Balthasar, they leave to search for the child, arriving to the altepetl of Jerusalem to ask 400-times lord Herod where the ruler of the Jews “is seated” (127). Confused because he is ruler of the Jews, Herod consults with three Jewish priests, decrying that “400 times you have confused people” and calling them lazy, pigs, rotten, scoundrels, and children of the devil. They quote Isaiah: “a wonderous flower with sprout, will bloom” and Micah, who says that in Bethlehem, a new ruler will come to “govern the altepetl of Israel” (131).

In pictorials, a tlatoque’s authority was marked by being seated on a reed mat, hence asking where the child is seated. Herod’s mistreatment of the Jews solidifies his vile character. The lines from Isaiah 11:1-2 have been modified, since flowers were associated with the divine, especially xochitlalpan, or the paradisical Land of Flowers.

Herod asks that the three rulers return to tell him where they locate the child and they leave. The star reappears atop the church, the messenger confirms the presence of a precious maiden whose beauty surpasses the precious flowers, an elderly person, and a shimmering, precious, wonderous child. The rulers alight from their horses, enter the church where Mass is going on, and after the Creed they approach the child.

Significantly, the play continues only after everyone has reiterated their faith by reciting the Credo.

Caspar greets the child as a precious jade, a quetzal feather, telling him that the carrying frame borne by Abraham and David has been set aside, “And truly the tail, the wing no longer has a mother, no longer has a father…. It is as if it stands beheaded. No longer is there anyone who is its head, who goes in front of it…” He admits that up until now, he was living in darkness, in gloom “since I did not know you” (137).

The drama here inserts Christ into native cosmology; the Nahuas considered nobles (pipiltin) the head and commoners (macehualtin) the tail and the wing. Both are necessary for society to function; lose the head or the wing and tail, and the bird will crash. Since only commoners use carrying frames, Nahuas in the audience would recognize that Abraham and David were not socially equal to the child. Per Caspar, the child is the new head, the new pilli, the new noble. Caspar’s speech, as editor Barry Sell notes, echoes the huehuetolli or speech of the elders in the Florentine Codex discussing the installation of a new ruler upon the death of a previous one. These speeches would have been familiar to Nahua listeners, underscoring Christ’s position as a ruler to replace Nahua rulers.

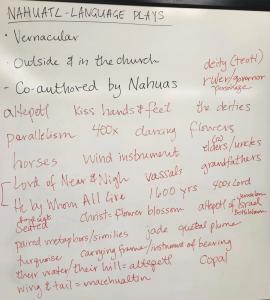

Notes from our in-class reading of the play

Melchior greets the child as “a really true man,” “a really true deity” (139), saying: “And in your lap, in your backpack your beloved, father, God, places the carrying of, the bearing of, the tail, the wing, who is to be saved.” He further states that Holy Mother Church “your water, your hill,” [i.e., altepetl/water-hill, or place over which you rule] will be placed within the child’s embrace, and “soon you will carry her in your arms, you will lull her to sleep” (141).

Hence the child, the new noble, will carry commoners on his back toward salvation – a reference to the Cross – but as the tail and wing are inextricably linked to the head, the child will necessarily carry commoners and nobles. Again, because only commoners use carrying frames, the child is both noble (per Caspar) and commoner (per Melchior). He is one of us. He is all of us. As for lulling the Church to sleep, the students and I weren’t sure about that reference.

Notes from our in-class reading of the play

Balthasar addresses the child last, saying he believes He is the The Lord of the Near, the Lord of the Nigh, He by Whom All Live, and telling him he will die stretched on a cross. Then he addresses the “precious, wonderous, and blessed maiden, original sin never reached you,” saying they [the rulers] have nothing to offer her, “only our spirits, our souls, and our lives” (143).

As my students pointed out, how would the magi have known the future? This is clearly meant to be didactic. It also appears as if the audience, united with the tlatoque, offer their spirits, souls, and lives to the Mother of God.

As the three rulers prepare to leave, an angel appears to warn them that Herod lied and wishes to kill the child, “But in no way is it time yet for him to die. Who will save the people of the world?” (145).

One can imagine the intensity of this moment, perhaps even the fright for those unfamiliar with the story.

After Mass ends, an angel cries out to Joseph to “Flee with the precious and wonderous sacred child! … Take him to Egypt under a large palm frond, hide him there so that [Herod] will not sentence him to death! He is coming to kill all the little children! Go speedily, O Saint Joseph!” [And thus, the play ends].

The palm frond would have been a familiar object to the Nahuas in central Mexico. And for those unfamiliar with the story, the drama ends in terrifying suspense.

References to Nahua culture I jotted down as we did our table read of “The Three Kings”

This post provides just a taste of the many fascinating references to Nahua culture in Nahuatl Christian drama, and are just one reason I love studying the origins of Mexican Catholicism. I, like many scholars, see collaboration rather than mere coercion in the complicated introduction of Christianity to the Americas.

As James Lockhart, the father of Nahuatl-language studies points out in The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries, “the religious history of postconquest Mexico has often been seen in terms of successful or unsuccessful resistance to a Christian conversion campaign.” There is no denying that forms of resistance emerged, however, “one can hardly speak of an indigenous inclination to disbelief in Christianity.” Because local peoples were accustomed to accepting the conqueror’s god, the Nahuas “needed less to be converted than to be instructed.” Overall, Lockhart asserts that “neither category, conversion or resistance, truly hits the mark” (203). Other scholars concur, such as Jonathan Truitt, who writes in his introduction to Sustaining the Divine in Mexico Tenothtitlan: Nahuas and Catholicism, 1523-1700 that “[t]he arrival of foreigners did not change people’s understanding of how they engaged with religion, it just changed the religion with which they interacted” (5).