Maybe let’s just all be a little better about recycling. Also really really listening to each other, and maybe being less judgmental and more forgiving but, also, owning up to our mistakes and being open to changing our own minds. Lead with our Understanding. You know: just being nice to each other. For once. And I’m talking about Everybody. (Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Everybody, p. 54)

So concludes Everybody, the modern adaptation of the medieval morality play Everyman, written by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2018. Reviews of the play were broadly positive, with critics finding the play to be particularly engaging because of its casting system (by lottery, with the actors finding out after the prologue what role they will play that night). As one reviewer wrote for Sightlines Magazine:

“It’s as if Jacobs-Jenkins’ script — which netted the playwright his second Pulitzer nomination — deliberately sets its actors up for failure. And this is what makes “Everybody” so completely engrossing and moving. Just as, in life, we are faced with the near impossible prospect of reaching perfection, and, most of the time, fall short; so, too, in this play, the actors are given real, near-impossible tasks to complete in front of us, risking public ridicule, courageously putting their bodies on the line.”

Another reviewer (this one for the Buffalo Spree, reviewing a production in Western New York) praised the play’s delivery of its core message:

“It’s this commitment to a stellar production, as well as the overt and on-the-nose timeliness of the play’s morality—we’re going alone, we can’t take anything with us, so the only thing worth investing in is love—that give this play its value. No matter how heavy-handed the delivery, you can’t ignore its message, nor leave without thinking about it . . . it tells us that life, too, is ephemeral, but the choices we make have lasting impact. Perhaps the play doesn’t say anything different from its predecessor because it doesn’t need to; more than 500 years later, we still haven’t learned the lesson it taught.”

I saw a production of this play with my students in March at a medieval studies conference, and I have to admit, I’d not heard of the adaptation before. I also have to admit that I had a very different impression from the second reviewer: the message of the play did indeed seem to be different from its medieval predecessor, and a return to the text of the medieval play confirmed my impressions.

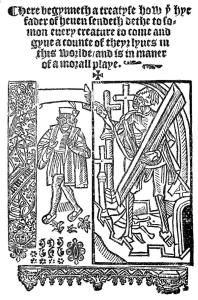

The medieval play, Everyman (otherwise titled A treatise how the high father of heaven sends death to summon every creature to come and give account of their lives in this world) is an example of a medieval morality play– one of the three main genres of medieval drama and the one considered to be the most “dull” by modern scholarly standards. Unlike mystery plays, with their humorous adaptations of scriptural tales, or miracle plays about saints (like the Digby Mary Magdalene, which involves dramatic special effects including Jesus on a zipline), morality plays consist primarily of dialogues between personified virtues and vices, with the ultimate triumph of virtue over vice. Everyman is a late-fifteenth century example of the genre and generally considered to be one of the best examples of medieval morality plays. It centers the journey of its protagonist, “Everyman”, as he seeks to convince characters like Fellowship, Kindred, Goods, Wisdom, Beauty, and Strength to help him with his pilgrimage to death. In this framing, the modern version does indeed match its medieval source text. But there are some key differences throughout, notably in the exchange of the characters “Confession” and “Good Deeds” for “Love” and in the framing of the play itself.

In the modern version, only “Love” accompanies Everybody into death, after an extended scene where Love reprimands Everybody for ignoring her and then requires Everybody to punish themselves, telling Everybody to yell out lines like “I’VE BEEN VERY DISAPPOINTING TO MYSELF BECAUSE MY BODY IS A MYSTERY TO MYSELF” or “I HAVE NO CONTROL” or “THIS BODY IS JUST MEAT.” (Jacobs-Jenkins, Everybody, 44-46). Only after Everybody has done this will Love agree to go with Everybody to the grave. In the medieval version, however, the character of Love is actually two different characters: Confession and Good Deeds. Instead of demanding self-punishment from Everyman, Confession and Good Deeds urge Everyman to, through the help of the character Knowledge, seek comfort from God’s grace. At Confession’s urging, Everyman thanks God for his gracious work and begins his penance, only then punishing his body for the “sin of the flesh” and strengthening Good Deeds to thus accompany him on his journey. There is still suffering in this scene– but the suffering is to an end, to an understanding of the ways in which Everyman focused on himself rather than on God and to shift Everyman’s focus heavenwards.

Even bigger differences show up at the beginning and end of the plays, in God’s prologue to the play and in the end of Everyman’s journey. In the modern version, God spends much of his opening address lamenting that humanity is not grateful for God’s perfection: emphasizing that he made the world as “only a whim– one experiment of many– taken up to simply see what could be” (Jacobs-Jenkins, Everybody, 12-13). Humanity’s failure has been in devouring the world God made, destroying creation rather than helping him build it. And the moral at the end of the play (quoted at the beginning of this piece) reflects this, with its admonition to “maybe recycle” and “be nice, for once.” In the prologue to the medieval original, God emphasizes that his frustration with humanity is that despite his work on the cross, humanity remains focused on material goods and riches, neglecting him. At the end of the play, Everyman’s final lines reflect a change in perspective, from the worldly allegorical figures that had preoccupied Everyman throughout the play to the person of Christ, so neglected according to God’s original lament. In fact, the final lines Everyman speaks in the play are about the work of Christ on the cross:

Everyman. Into thy hands, Lord, my soul I commend;

Receive it, Lord, that it be not lost;

As thou me boughtest, so me defend,

And save me from the fiend’s boast,

That I may appear with that blessed host

That shall be saved at the day of doom.

In manus tuas–of might’s most

For ever–commendo spiritum meum.

What a contrast to the ending of the modern version, where Everybody’s final words are “Wait! WAIT! WH–” (Jacobs-Jenkins, Everybody, 51) as both Love and Evil pull Everybody into the grave.

So, what to make of these differences? Does a medieval morality play work when secular modern conceptions of morality are substituted for religious ones? That’s perhaps up to the audience, but for me, I think it was striking to see just how little is left of a morality play when “morality” is left up to the individual to determine and when the gospel of humanity’s failure and Christ’s redemptive work is replaced with a vague idea of “be kind.” It made me think about what cultural values we see reflected in the play’s versions. Whether perfectly or imperfectly, the medieval version reflects a Christocentrism that ultimately makes it possible to end the play with certainty: medieval audiences knew what was happening after Everyman’s death, and the play knew what anchored a “good life”- a life centered on Christ. In the modern version, a lot of questions remain. What exactly anchors a good life? Is it simply keeping in mind that things can’t come with you? Is it treating the earth and other people well? Is it knowing yourself and accepting that things can’t be controlled? Or is it all a mystery that ends in confusion? Everybody certainly seems to say that the meaning of life is what you make it– as long as you make it thoughtfully and with the knowledge that you will die. I also wondered, though, what messages we might see in other modern media, shows or plays or music meant to reflect modern Christian morality. For all their differences, Everyman and Everybody certainly reflect broad cultural frameworks and assumptions- would a modern Christian morality play look more like its medieval predecessor or its modern companion? And what does it tell us about our modern faith and culture if the answer is the latter?