“If you converse with these missionaries of Christian civilization, you will be surprised to…meet a politician where you expected to find a priest.” In the almost 200 years since Alexis de Tocqueville wrote those words, evangelicals have often found themselves playing the role of politician instead of priest. And along the way, there have been others who question this role reversal. After all, Jeremiah 29 does not seem to leave room for those attempting to become kings.

Evangelical historians over the last fifty or so years have often been this sort of gadfly—questioning and problematizing this sort of partisan overreach from evangelical talking heads. This has led to internal strife within evangelicalism, as Joey Cochran helpfully demonstrates in his column yesterday. I want to single-out and describe two moments where this happened. Along the way, I’ll inadvertently talk a bit about some other pieces I’ve had the honor of writing here at The Anxious Bench. I think the bench has powerfully continued this tradition of being “sheep in wolves clothing.” Hopefully, the meaning of this phrase and the call it represents for young evangelicals will become clear through my piece.

Prior to the 1970s and specifically the work of George Marsden, evangelical Christians generally didn’t often become historians—at least not historians who trained in the “secular” academe. Soon after he began teaching at Calvin College with a Yale PhD. He was not alone for long though. Other evangelicals began to follow his lead. Their ranks included the likes of Nathan Hatch, Skip Stout, Mark Noll, and Grant Wacker.

In 1980, with the election of Ronald Reagan imminent, Newsweek published a small article entitled “Guru of Fundamentalism.” The guru was an odd-looking man named Francis Schaeffer. While Schaeffer was not well-known outside conservative, Protestant circles, his influence within those communities was and continues to be outsized. Nor was the title of guru entirely inappropriate. Although he went by “Dr. Schaeffer,” he had never pursued doctoral studies or written anything of an academic nature. In the article, a historian at the evangelical Wheaton College named Mark Noll was quoted as saying “The danger is that people will take [Schaeffer] for a scholar, which he is not. Evangelical historians are especially bothered by his simplified myth of America’s Christian past.”[1]

As soon as the article hit newsstands, Noll wrote to both Schaeffer and Kenneth Woodward, who had written the piece. To Schaeffer, Noll attempted to explain that while the article only quoted him critically he had spoken positively and extensively of Schaeffer’s influence on Fundamentalist and evangelical Christianity in America. To Woodward, Noll enquired why only his critical quotes had made the final cut. Woodward never wrote back. Schaeffer however wrote back almost instantaneously with a twelve-page, double spaced tract. In the letter, he instructed Noll on how to do the work of history, chided him for his naiveté, and demanded evangelical historians step back into line with what he saw as Conservative Protestantism’s political goals. The letter touched off over a year of correspondence between Schaeffer and a group of evangelical academics including Noll. Their letters tell us the beginning of a conflict that continues to rage within conservative, Christian America: “What does American history mean and how has Christianity shaped it?” By the time this correspondence began though, Schaeffer was incredibly influential, indeed “…all these men [Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Tim LaHaye, and Cal Thomas] cited Schaeffer’s narrative of Western history…as a critical influence on their own work.”[2] This was a story of Manifest Destiny, American heroism, and a shining city upon a hill filled with theological pilgrims. This story has been told loudly in megachurches and by activists, apologists, and pastors. From this perspective, the role of an academic historian would be to defend and flesh out a constructive and optimistic view of Americana and her past that evangelicals in the pews were already sympathetic towards.

Instead, many of them, including Noll had participated in a quieter undercurrent, an alternative narrative of American history within Conservative Protestantism. While imperfect, this narrative was told by historians. It sought to divert from the story told by Schaeffer and other talking heads towards a more nuanced and grounded story, which might even highlight the United States’ failings. Men like Noll who had grown up in conservative, even fundamentalist homes, but (often inspired by Schaeffer) found their way into the academy. Here they found themselves parting company with the narratives of history they had been taught, and which initially brought them to study the subject professionally. In short, the evangelical historians assumed that others who shared their same background and beliefs would be willing to take the same intellectual journey they had.

This is the difference between competing understandings of history within evangelicalism. The historians believed history must be critical, even prophetic. Others have seen long-term political goals as more important than the truth of history. Francis Schaeffer wrote to Mark Noll in 1983, “In summary, I am sorry but I do think unless you change the direction of your writing toward the direction I have suggested above that you will prove to be as destructive in the midst of the severe needs of our day…” Finally, in May 1984, as the correspondence was winding down due to intransigence, Marsden replied to a letter from Schaeffer, originally sent to Noll, that “Consequences of what one might say should, of course, be taken into account; but the crucial thing to seek is to get things right. Otherwise, we will be left with a pragmatic standard for what we say—a result that you lament in other contexts. So we cannot tailor our historical generalizations just to suit the needs of the moment—even if they be urgent needs.”

A decade later, in 1993, Harry Stout published a well-received, scholarly biography of George Whitfield. Stout had studied at Princeton and was a compatriot of Noll, Hatch, and Marsden. He even endorsed their book In Search of a Christian America, which rejected Schaeffer’s providentialist history.[3] Stout’s was the first truly academic biography to be published of the evangelist. Most volumes written about the famous English preacher had taken the form of hagiographies written by those who revered him as a saint in all but name.

The book quickly proved controversial in Reformed theological circles. Iain Murray’s Banner of Truth published a scathing review. The reviewer’s primary criticism was that Stout spent too much time on Whitefield’s foibles rather than focusing on his holiness and how the revivalist had been used by the Holy Spirit. “Psychology and dramatics cannot account for Whitefield’s extraordinary success. To suggest that they do is unhistorical and mean-spirited” wrote the reviewer. He argues that Stout’s Whitefield is an “alternative interpretation” of “this great servant of God.” The reviewer concludes by suggesting that “Stout needs to make himself familiar with the great evangelist.”

Stout responded with an extended letter to the editor, after first passing it on to Noll. In the letter, Stout laid out his credentials both as an evangelical Calvinist and as an academic historian to defend his writing “I think my biography succeeds in doing what it set out to do. The professional academy now respects Whitefield in ways they were not prepared to do earlier.” He concludes with a prophetic word: “If I must be read out [of the camp of reformed evangelicalism], then I’m read out. But be aware of what you’re saying when you read me out, because…you just may be painting a sheep in wolf’s clothing.”[4]

Before publishing Stout’s letter, Murray replied to him privately in a more congenial tone than the review held. He reiterated his theological concerns, but went so far as to ask Stout’s opinion on some of his own writing about Jonathan Edwards. Less than a year later, Noll too would find himself in conflict with Rev. Murray. In the spring of 1995, not long after Stout’s letter was published, he reviewed Murray’s Revival and Revivalism: The Making and Marring of American evangelicalism, 1750-1858 in the pages of Christianity Today. While Noll’s tone was slightly more sympathetic than Stout’s letter, he still took deliberate aim to correct the Providential historiography. Noll writes

With Iain Murray however, history is an explicit subdiscipline of theology…For at least a few readers (like myself) who share Murray’s Calvinism, but who also think that historic Calvinism justifies an approach to historical study focusing on evidence and interpretations open, in principle, to all observers—this book will be an exasperation.[5]

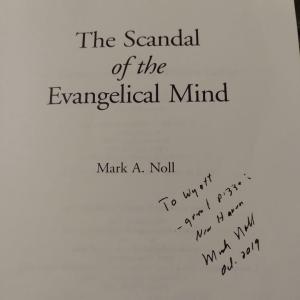

Around this same time, Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind was first published. It famously opens with the line “The Scandal of the evangelical mind is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.” This “epistle from a wounded lover” as Noll describes the book, detailed the history of evangelicalism’s non- and anti-intellectualism accompanied by a hope for a renewed evangelical mind. It is interesting to note, that Noll appears to have borne Schaeffer no ill-will, or at least was too politic to mention their quarrels in Scandal. His only brief mention of Schaeffer comes at the end of the book and is reasonably positive. This generosity both from Noll and Stout is a characteristic of which I have benefitted immensely.

I first met Mark Noll during the 2019 World Congress on Jonathan Edwards at Yale Divinity School (providentially, also the weekend I met Joey Cochran, which led in a way to me writing this piece). I emailed him a couple of weeks before the congress was to occur. My emailed detailed that there were a few of us who had grown up evangelical and still tried to hold onto that label; we would love to sit down and talk with him at some point during the event. We would make anything work. Would he consider talking at the conference, coffee, drinks, or even a dinner? Professor Noll replied promptly and offered to get dinner with my friends and me the first night of the conference. It was only later that I discovered he had skipped a speakers’ dinner in order to join us. We sat over New Haven’s finest pizza and just talked. He treated us like colleagues.

But the generosity did not end there. Not only did Professor Noll eventually send me copies of several letters and essays from his private files, but he even helped me edit what became my first public bit of writing—this essay on the role of historians.

Similarly, Professor Stout took me under his wing and offered advice, food, and free books. Inarguably the three things graduate students need the most. I know I am without a doubt a recipient of only a fraction of his kindness, but it changed my life and intellectual trajectory. My classes with him, as well as simply watching his example in how he deals with everyone around him have shaped the type of academic and intellectual I aspire to be.

I add these anecdotes for two reasons. First, I think many of us in academia who grew up evangelical and still love historical orthodoxy and the great tradition in which we stand often feel like we are being “painted as sheep in wolves clothing.” It’s a lonely role to love both the University and the Church. It draws one into a role Makoto Fujimura has described as the borderwalker.[6] Second, the way out for all of us who inhabit the church, historians and otherwise is simple but incredibly difficult. Generosity. Giving of ourselves, especially to those with whom we disagree and to those who may never be able or choose to repay us. I learned this lesson from evangelical historians. I hope we can remember the lesson and aspire to teach it to others with the hope of these lines from Wordworth that I find myself returning to again and again. “What we have loved, others will love and we will teach them…”

[1] Hankins, B. (2007). “I’M JUST MAKING A POINT”: FRANCIS SCHAEFFER AND THE IRONY OF FAITHFUL CHRISTIAN SCHOLARSHIP. Fides Et Historia, 39(1), 15-34. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/im-just-making-point-francis-schaeffer-irony/docview/229933475/se-2

[2] 1. Molly Worthen, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016). 214

[3] As Augustine reminds his readers in City of God, we cannot easily or accurately read the will of God from the events of history.

[4] Draft copy in author’s possession.

[5] Draft copy in author’s possession.

[6] It’s interesting that Tolkien in discussing Aragorn, whom Fujimura uses as a model of this role in Culture Care, has Frodo say “I think a servant of the enemy would look fairer and feel fouler.” I think this is the experience of being a sheep painted in wolves’ clothing.