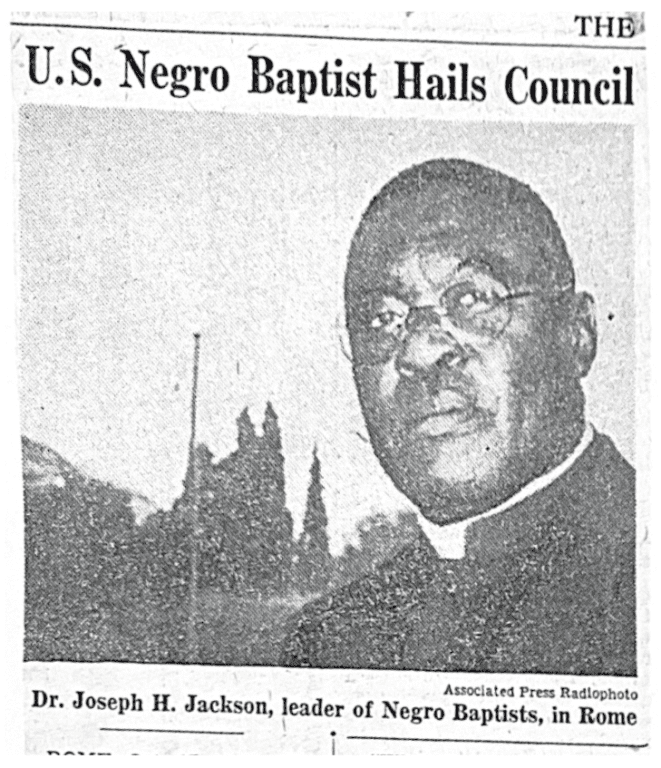

In October 1962, the New York Times ran an article entitled “U.S. Negro Baptist Hails Council.”[1] The “U.S. Negro Baptist” in question was Joseph Harrison Jackson, pastor of Olivet Church in Chicago and president of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc. (NBC). The “council” referred to the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican held in Rome. Whereas the World Baptist Alliance declined to pursue an invitation to Vatican II, Jackson was the only Baptist observer invited by Pope John XXIII. Jackson had met the Pope a year prior to discuss challenges to Christian unity and the plight of Black Americans.

I was not looking for Jackson when I found him in the archives, digging through Baylor University’s archives on the ecumenical movement. Honestly, I was surprised to discover him at all. As a Ph.D. student researching liberal Protestants in America, I had a particular image of them in mind: older, White, upper-class Protestants from mainline denominations. I knew a hurdle I would have to overcome concerned how race played a part in discussions around religion and politics in America. Jackson’s role in those discussions interested me. As a more conservative voice in American religion and politics, his role in the ecumenical movement is vital to understanding the movement for Christian unity.

Jackson’s story is more commonly remembered for his role in the Black American struggle for civil rights. In August 1964, the New York Times ran an article showcasing twenty-four Black Americans advocating for their civil liberties in the United States. Some faces are familiar: Martin Luther King Jr, Adam Clayton Powell, and Malcolm X make the list. Jackson appears in the top row as leader of the “largest Negro religious body in the nation… headed since 1953” and a figure who had “frequently been in conflict with Negro leaders over his calls for patience and maintenance of goodwill, and his consistent opposition to demonstrations, including the March on Washington.”[2] The Times places Jackson where scholars of the civil rights often place him: opposed to Martin Luther King, Jr.

This is not unusual considering the relationship between the two pastors and the origins of the Progressive Baptist National Convention (PNBC), the denomination King eventually joined. King and other young pastors, working towards civil rights, saw the church as an engine to arrive at the political goals they desired. Jackson disagreed.

Jackson’s political views are explored most effectively in historian Peter Paris’s Black Religious Leaders: Conflict in Unity (1991). To Paris, Jackson supported efforts to earn greater civil rights for Black Americans, but he was conflicted on the purpose of the church and the proper way to achieve civil liberty. “It is difficult to make a sharp distinction between Jackson’s religious thought and his political thought,” he wrote. Paris settled on Jackson’s optimistic view about the ability for White and Black Americans to overcome their differences using the legal systems already established.[3]

Some of Jackson contemporaries, such as Gardner C. Taylor and L. Venchael Booth, would have disagreed. Progressive pastors felt the NBC should make more explicit political and monetary decisions in the civil rights fight.[4]Upon Jackson’s fifth term as president, progressive members of the denomination brought charges against him for violating the convention’s constitution. Jackson won his trial but failed to smooth things over with the younger pastors. Tensions were high and things finally came to head between progressive and conservative pastors in the Black denomination in October, 1961. During the NBC convention in St. Louis, progressive members of the conference marched on stage and demanded the podium. During the struggle for the podium, one conservative pastor fell from the stage and later died from his injuries.[5]

For most narratives of the civil rights movement, this is where Jackson quickly enters and exits the story. But focusing on this moment of discontent discounts a majority of Jackson’s life, especially his devotion to the cause of Christian unity. His friendships and experiences with Christians of different races and denominations colored his political beliefs and how he advocated for Black Baptists on the world stage. David Wills, writing about Black Christian’s relationship to White mainline denominations, argued that Black church leaders preferred to move within Black spaces, making the passing comment that “the typical AME bishop or the pastors of such great metropolitan Black Baptist churches as Olivet in Chicago or Abyssinian in New York did not seem to envy… Benjamin Mays [for] his ecumenical prominence.” But this implies that Jackson, the pastor of Olivet in Chicago, did not have an “ecumenical prominence” all his own.[6]

Sadly, Jackson continues to be a figure defined by the division within his own denomination rather than his commitment to Christian unity. The purpose of much of Jackson’s ecumenical work was not just domestic success for Black Americans, but “to see that black Baptists had an impact on the wider world in terms of missionary outreach, material aid, and education.”[7] By typecasting Jackson as a foil to the more progressive and well-known Martin Luther King, Jr., Jackson’s life is diminished and our understanding of the civil rights movement loses some of its life.

From Rudyard to Rome: Jackson’s Origins, Ecumenicalism, and Vatican II

Jackson’s story doesn’t start at the National Baptist Convention in Kansas City in 1961, but in Rudyard, Mississippi in 1900. Jackson writes in his book, Many But One: The Ecumenics of Charity, that Rudyard was not only the place of his birth, but where he “was converted… as a child, accepted the Christ-way of life as the way of salvation, and for the first time, learned to rely on the love of God in Christ Jesus for salvation, for guidance, and for the hope of eternal life.” Jackson grew up in a primarily Baptist community, but quickly began to “[make] contact with peoples in other communities,” such as the “bishops of the A. M. E. Church, leaders and thinkers of the other branches of the Methodist church and… Presbyterians and Congregationalists talk with authority and power about the wonderful works of God.” He was ordained as a minister in 1922.[8]

Jackson attended Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska in 1934 and earned his M.A. in Education. Jackson’s enrollment at the Jesuit institution put the Black Baptist in contact with White Roman Catholics for the first time. Jackson recounted that he “never developed a fear of Catholics” unlike other Baptists of the time.[9] In 1935, Jackson was elected as the Secretary of the Foreign Mission Board of the NBC.[10] In 1937, Jackson visited Oxford University and the newly-formed Ecumenical Council on Life and Work.[11] His ecumenism began to take on an international scope. Jackson worked on advancing the central message of those early meetings: “Let the church be the church.”[12] This organization formed the basis of what became the international World Council of Churches (WCC). Jackson attended the first gathering of the WCC in Amsterdam in 1948. He led the assembly in morning worship during the Second Assembly of the WCC in Evanston, Illinois, in 1954.[13]

In December 1961, two months after the PNBC split from the NBC, Jackson sought a meeting with the Pope “after some lobbying from Chicago Catholics,” including the mayor of Chicago, Richard J. Daley.[14] The Pope accepted a meeting with him. Jackson perceived that the spirit of ecumenicism had swept through the Vatican and talked with the Pope about how they could collaborate to foster unity between Roman Catholics and Protestants. He shared with the Pope “some of the hopes, desires, aspirations, and life struggles of my own people.”[15] Jackson did not “assume to speak for all men of color” but looked to bring attention to the suffering of Black people in the United States and around the world.[16] Their meeting went well, and Jackson left Rome encouraged that his time had helped the cause of Christian unity. Five days after their meeting, Pope John XXIII officially declared the formation of the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II).

Jackson was abroad when the council started, attending the Third Assembly of the WCC in New Delhi, India. During the first session of the council, Jackson submitted the “Bill Regarding the Problem of Mixed Marriages Between Protestants and Catholics.” Jackson hoped a more nuanced position on interfaith marriage would encourage “Christian unity in general and a more wholesome fellowship between Roman Catholics and Protestants in particular. Jackson also wrote the Pope directly, inspired by shifts in Roman Catholic doctrine towards the “desire” that Protestants and Roman Catholics might be unified in Christ. Jackson left Rome “rejoicing in the certainty of Christian victory, richer in the depth of Christian fellowship that extends across denominational lines and is sustained by faith, hope, and love.” He rejoiced over the recent progress the World Council of Churches and the Roman Catholic Church had made towards a common goal of ecumenism.[17]

Jackson co-labored with others in the ecumenical movement throughout the 1970s and served as President of the NBC until 1982. He passed away in 1990.

Lessons From Joseph H. Jackson

During my research, I came across an article in the September 1976 issue of the Winston-Salem Journal by Virtie Stroup. Speaking to the NBC convention in Dallas, Jackson warned members of the denomination against the threat of communism. However, it concluded with a section about theology that has been influential to the way I think about the Black religious tradition in the United States:

The hope and strength of the church, Jackson said, comes from its past. “…to those theologians who believe that a segregated church is the true church of Jesus Christ, I ask you to go back to Calvary for correction, for wisdom and for guidance… and stand quietly in the shadows of the Cross of Jesus Christ and look again upon a head crowned with thorns and a face matted with His own blood, hear the message from the wound in His side, and learn more about the living God in the presence of suffering humanity.”[18]

When historians characterize and stereotype figures in history to fit their own narratives or the narratives of the previous generations, they often simplify figures. The complexity of their times, their lives, and their voices are lost to the cacophony of the modern moment. Not only does the hope and strength of the church come from its past, but so too does our own hope and strength as historians. Knowledge of the past helps us navigate the present darkness, the injustices of our day, by the guidance of the luminous light of those who came before us. We must take care not to lose precious lessons of history by flattening the stories of unlikely sources like Joseph H. Jackson, a subject of history who has much to offer us today.

• • •

Today we have the pleasure of welcoming Will Franks, Ph.D. student at Baylor University. Franks is interested in modern American politics and religion, the origins and intersections of political and religious identity in the face of modern political division and realignment, and the liberal/conservative divide in American religion, both in how it is experienced by individuals and how it has been written about by academics. Learn more about the history and influence of Joseph H. Jackson from Dr. Jared E. Alcántara of Baylor University, who has a forthcoming book entitled, The Challenge of Joseph H. Jackson: How America’s Most Powerful Black Preacher Became a Forgotten Man (Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2024).[19]

[1] “U.S. Negro Baptist Hails Council.” New York Times, October 18, 1962. https://nyti.ms/3V9j1U6.

[2] “Organizations and Leaders Campaigning for Negro Goals in the United States.” New York Times, August 10, 1964. https://nyti.ms/3ItYamU.

[3] Peter J. Paris, Black Religious Leaders: Conflict In Unity (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1991), 74.

[4] William D. Booth, A Call to Greatness: The Story of the Founding of the Progressive National Baptist Convention (Lawrenceville: Brunswick Publishing Company, 2001), 5–6.

[5] For more information about the NBC/PNBC split from the PNBC point of view, see William D. Booth, A Call to Greatness: The Story of the Founding of the Progressive National Baptist Convention (Lawrenceville: Brunswick Publishing Company, 2001). For the NBC perspective, see Joseph H. Jackson, A Story of Christian Activism: The History of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc. (Townsend Press, 1980).

[6] David W. Wills, “An Enduring Distance: Black Americans and the Establishment,” in Between the Times: The Travail of the Protestant Establishment in America, 1900-1960, ed. William R. Hutchison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 187.

[7] Wallace Best, “‘The Right Achieved and the Wrong Way Conquered’: J. H. Jackson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Conflict over Civil Rights,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 16, no. 2 (2006): 195–226, https://doi- org.ezproxy.baylor.edu/10.1525/rac.2006.16.2.195.

[8] Joseph H. Jackson, Many But One: The Ecumenics of Charity (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1964), 167–68.

[9] Wallace Best, “‘The Right Achieved and the Wrong Way Conquered’: J. H. Jackson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Conflict over Civil Rights,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 16, no. 2 (2006): 215.

[10] “Jackson, Joseph Harrison,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/jackson-joseph-harrison

[11] Joseph H. Jackson, Many But One: The Ecumenics of Charity (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1964), 168.

[12] Joseph H. Jackson, A Story of Christian Activism: The History of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc. (Townsend Press, 1980), 499.

[13] W. A. Visser ’t Hooft, The Evanston Report: The Second Assembly of the World Council of Churches, 1954 (SCM Press LTD, 1955), 56.

[14] Wallace Best, “‘The Right Achieved and the Wrong Way Conquered’: J. H. Jackson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Conflict over Civil Rights,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 16, no. 2 (2006): 215.

[15] Joseph H. Jackson, A Story of Christian Activism: The History of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc. (Townsend Press, 1980), 502.

[16] Joseph H. Jackson, A Story of Christian Activism: The History of the National Baptist Convention, U.S.A., Inc. (Townsend Press, 1980), 502.

[17] Joseph H. Jackson, Many But One: The Ecumenics of Charity (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1964), 172, 202–203.

[18] Virtie Stroup, “Black Leader Says Marxism Gaining,” Winston-Salem Journal, September 9, 1976.

[19] “Jared E. Alcántara, PhD,” https://truettseminary.baylor.edu/person/jared-e-alcantara-phd. “The Challenge of Joseph H. Jackson,” https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-challenge-of-joseph-h-jackson-9780197598818