This summer three theologically conservative Protestant denominations held their annual conventions. All three made news for their decisions regarding women. But the three have radically different polity, which is to say they govern themselves differently. I’m fascinated by how polity seems to affect deliberations on the role of women in the church, even among churches that share a similar belief in the veracity of the Bible.

All three denominations believe the Bible to be accurate according to what they understand to be a plain reading. And all three believe that the Bible teaches that some church roles are reserved for men. The Baptist Faith and Message 2000, the statement of faith with which SBC member churches must be in substantial agreement, limits the role of “pastor” to men. The PCA limits the role of “elder” to men, and specifies that it entails both teaching elders (all pastors) and governing elders (the elder board). The ACNA limits the role of bishop to men.

But this summer, all three denominations faced attempts to push their stance on women in a more conservative direction. Their polity affected the outcome. Let me explain.

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is congregational. That means each local congregation is autonomous. It can do what it wants. The national convention is a voluntary association of local congregations for the purpose of mutual support and united efforts in missions and service. The national convention can set the parameters for participation, but it can’t instruct a local church on what to do. It can only disfellowship one. The annual meeting of the SBC is conducted by lay delegates, known as “messengers,” of member churches.

The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) is organized differently. Local churches are governed by a board of elders known as a session. Sessions in turn are accountable to a regional presbytery. Finally, the whole denomination is governed by the General Assembly. Membership in each of these bodies is restricted to ordained elders. (I like to joke that historians love Presbyterians because they are perfectly designed to generate the maximum amount of paperwork.)

The Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) operates on an episcopal (bishop-based) system that combines elements of both the Baptist and Presbyterian approaches. The ACNA is split into dioceses. Each diocese is headed by a bishop. The council of bishops in turn selects an archbishop for the whole province. Meanwhile, each church in a diocese is served by a priest or priests accountable to the diocesan bishop in spiritual matters. Each church also has a vestry consisting of elected lay members who conduct the temporal business of the church, largely involving the distribution of funds. Each diocese conducts business in a meeting consisting of both clergy and lay delegates and each diocese likewise sends clergy and lay delegates to conduct business at the provincial assembly.

Here’s how these different systems get fun when it comes to women’s roles in the church. A local Southern Baptist church can do whatever it wants. But it can get kicked out of the SBC if enough messengers decide its stance is not in substantial agreement with the SBC’s take on the issue. PCA churches have to toe the PCA line and there is accountability at every step of the hierarchy. ACNA churches have to keep in step with their diocesan bishop’s policies, but other bishops in the province can maintain different policies.

The extent to which women speak into denominational politics also differs by polity. SBC messengers and ACNA lay delegates are not ordained. They therefore consist of both women and men regardless of the churches’ stances on women’s ordination. The PCA by contrast is governed solely by elders at every level. Because the denomination does not ordain women, all denominational business is therefore conducted by men.

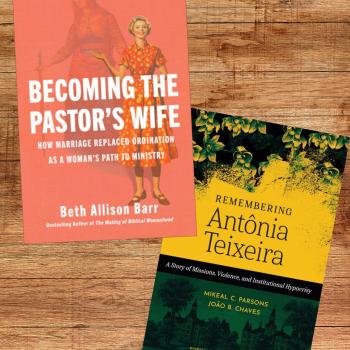

Changing the SBC constitution requires 2/3 of the messengers to the annual meeting to vote to do so two years in a row. This summer constituted the second vote on what was called the Law Amendment, after Pastor Mike Law, who proposed it. The amendment sought to define the “pastor” that could only be male quite expansively: not only what we would think of as the “senior” pastor, but also any associate pastors or staff members operating in a pastoral role without the title. It got more than 50% of votes, but less than the required 2/3. Too many SBC churches had female associate pastors, typically women’s or children’s pastors, or simply a commitment to local church autonomy within broad agreement.

Meanwhile, the PCA requires a passing vote by the General Assembly two years in a row plus approval of 2/3 of the presbyteries to change its regulations. This year, it faced two questions about women’s roles in the church. Its General Assembly held the second vote on a motion forbidding PCA churches from ordaining women even as deacons (a position involved in official service to the church but not church governance)—and it passed. The denomination also held a first vote on whether PCA churches should be forbidden from having a woman preach, as distinct from serving as an elder. It failed. It seems that ordaining a deacon is easily defined but nailing down the definition of preaching made the latter motion too cumbersome.

Finally, the ACNA selects a new archbishop every 5 or 10 years (to a 5-year term, renewable once). The “College of Bishops” (all of them) gathered in a closed “conclave” to select the bishop for this role. There was a considerable amount of hoopla leading up to the conclave centered on the question of women’s ordination, not as bishops but as priests. Some ACNA dioceses ordain only men to both the diaconate and the priesthood, some ordain women to the diaconate but only men to the priesthood, and some ordain women to both the diaconate and the priesthood. In other words, each diocese makes its own policy on the issue, considered secondary, while all must agree on things considered primary, like biblical authority, the Nicene Creed, and the episcopacy.

One entire diocese and one group of priests from various dioceses sent petitions to the College of Bishops asking them to undo this compromise and limit ordination to the priesthood to men. Their rationale was greater unity: some members of dioceses that ordain only men to the priesthood cannot receive the Eucharist from a female priest as a matter of conscience. The selection of the next archbishop was understood to take the pulse of the College of Bishops on this issue.

The bishops selected Steve Wood, Bishop of the Diocese of the Carolinas, to be the next ACNA archbishop. Wood and his diocese believe in ordaining women to both the diaconate and the priesthood, but, interestingly, not in appointing a woman as “rector” (senior pastor) of a local church, as occurs in some other dioceses. Their rationale is that the Bible says nothing about who celebrates the Eucharist (the defining role of a priest in the Anglican tradition) but does make statements they interpret to limit ultimate governing authority to men. Wood is thus a moderate candidate of sorts on this issue. More importantly, it seems, Wood’s diocese focuses on evangelism and church planting. His selection appears to indicate that the ACNA continues to believe women’s ordination to be a secondary issue worth compromising on for the sake of cooperation in what it judges to be more important activities of the Christian faith.

All three denominations exhibited some nuance around the question of women’s roles in the church. But the grace and space around the question was larger in the Anglican and Baptist denominations than in the Presbyterian one. This fact suggests that when lay women have an official channel for speaking into the denomination, their perspectives change the perspective of the denomination as a whole. By contrast, when there is no official channel for lay women to voice their experiences, denominations seem more likely to double down on restricting them.