In the spring semester, I did a bit of research towards a project that while a bit outside my wheelhouse, is influencing my methodologies in ways I think are interesting and important. I’ll be presenting a version of this project at a conference this fall, and I thought I might introduce a bit of it here also. This will be part one of a series over the next couple months where I explain my process and introduce pieces of what I discovered along the way. I began looking into this project because of a hunch. I suspected that James Cone (the founder of Back liberation Theology) and Vine Deloria Jr. (one of the most important Native American intellectuals of the twentieth century) had been friends. I suspected this because of how a few scholars seemed to have studied under and been influenced by both of them. I really had nothing hard to go off of though until I spoke with Deloria’s son, Phil–now a distinguished professor at Harvard. He told me that they had been friends and I should hunt down the connection. Luckily, I live next door to Yale where Deloria’s papers are stored and am a PhD student at Columbia, where Cone’s papers are housed. I dug into the archives and began to discover a beautiful and influential friendship. I begin to tell its story below with these epigraphs.

As with any generation

The oral tradition depends on each person

Listening and remembering a portion

And it is together—

All of us remembering what we have heard together—

That creates the whole story

The long story of the people.

~Leslie Marmon Silko

“Our ‘religion’ is not what we profess, or what we say, or what we proclaim; our ‘religion’ is what we do, what we desire, what we seek, what we dream about… One’s religion, then, is one’s life, not merely the ideal life but life as it is actually lived.” ~Jack Forbes

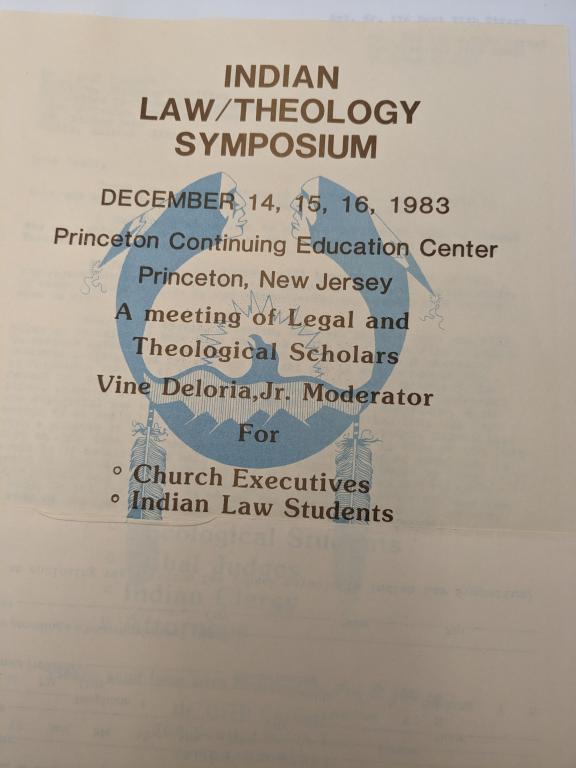

“Whether Indian peoples and indigenous peoples are to be treated as human beings, having essentially the same rights as other human beings, or whether, on the contrary, they are something different and therefore to have different rights under the law has been a question which has engaged the intellect of theologians as well as legal scholars for some centuries.”[1] Vine Deloria Jr. wrote these words in an abstract circulated before a 1983 conference entitled “The Symposium on Indian Theology and Indian Law.” The conference was hosted at Princeton University and co-sponsored by the Cook School for Theological Training, a largely Native school. One of the other speakers at the conference was James Cone, professor of Theology at Union Seminary in New York City. Deloria had told his co-convener, Cecil Corbett that Cone was the most important theologian, whose presence would be necessary for the conference’s success.[2] Cone and Deloria had been friends for nearly a decade by the time Deloria wrote to him inviting him to participate in the Princeton conference.

In his talk, titled “Translation and Transformation: Some Problems in the Formulation and Interpretation of Indian Rights,” Deloria lamented that the Native American rights movement did not possess the same intellectual rigor and firepower as the Civil Rights movement had. He described an argument with one of the leaders of AIM who told students to drop out of college and become activists. Deloria contended that “If we were really serious about making America pay its long overdue bill, we needed two students in the library for each protestor that marched to Washington or sat on Alcatraz or other surplus federal property. My estimate was exceedingly low.”[3] Both Cone and Deloria labored to fix this imbalance. Through their work and advisory capacities, they shaped a new generation of Native intellectuals. Many of these thinkers saw themselves living in the space between Vine Deloria Jr. and James H. Cone, the space of their friendship.

James Cone is perhaps the most important Black theologian between the death of Martin Luther King Jr. and his own passing in 2018. Having studied at historically Black colleges, Cone eventually received his doctorate from Northwestern University. Almost immediately, he became a lightning rod in the theological world. In his first book, Black Theology and Black Power, Cone dropped a bomb. Remembering how he wrote the book, Cone describes seventeen hour writing days with his only real breaks being Sundays spent immersed in the black church community, hearing sermons and living with a community pastored by his brother. It was through this book that he began to propagate a particular form of theology, which he would come to call Black Liberation Theology. “Black liberation theology came out of black culture and religion, and it celebrated a new freedom to talk about God and Jesus in a jazz mode, a blues style, and with the sound of the spirituals.”[4] In constructing this theology, Cone saw himself as shaped by the influence of both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In a posthumously published memoir, Cone writes “The King assassination was a turning point in my life. As long as King was alive I had hope that white America could be converted to seeing Negroes as human beings… Malcolm repeatedly told King and the Negro masses that white America had no conscience and would never treat blacks as human beings unless we forced them. Malcolm’s words were ringing true.”[5] On the strength of this book and a second, published less than a year later, Cone was hired as professor of systematic theology at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Union was without a doubt the most influential progressive Protestant seminary. Both Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich, arguably the most influential white theologians of the twentieth century, had taught at Union for the majority of their careers. Cone was the first African American to hold a professorship at Union.

James Cone is perhaps the most important Black theologian between the death of Martin Luther King Jr. and his own passing in 2018. Having studied at historically Black colleges, Cone eventually received his doctorate from Northwestern University. Almost immediately, he became a lightning rod in the theological world. In his first book, Black Theology and Black Power, Cone dropped a bomb. Remembering how he wrote the book, Cone describes seventeen hour writing days with his only real breaks being Sundays spent immersed in the black church community, hearing sermons and living with a community pastored by his brother. It was through this book that he began to propagate a particular form of theology, which he would come to call Black Liberation Theology. “Black liberation theology came out of black culture and religion, and it celebrated a new freedom to talk about God and Jesus in a jazz mode, a blues style, and with the sound of the spirituals.”[4] In constructing this theology, Cone saw himself as shaped by the influence of both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In a posthumously published memoir, Cone writes “The King assassination was a turning point in my life. As long as King was alive I had hope that white America could be converted to seeing Negroes as human beings… Malcolm repeatedly told King and the Negro masses that white America had no conscience and would never treat blacks as human beings unless we forced them. Malcolm’s words were ringing true.”[5] On the strength of this book and a second, published less than a year later, Cone was hired as professor of systematic theology at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. Union was without a doubt the most influential progressive Protestant seminary. Both Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich, arguably the most influential white theologians of the twentieth century, had taught at Union for the majority of their careers. Cone was the first African American to hold a professorship at Union.

Vine Deloria Jr was perhaps the most important Native intellectual of the second half of the twentieth century. While two volumes promising at least partial biographies of Deloria have beenpublished in the last few years, neither really offer us a complete figure of the man. And unlike Cone, Deloria never published a memoir. Instead, then, we must glean what we can from his essays, correspondence, and reminisces from his students and friends. Both Weaver and Warrior note that in private Deloria was quite insecure about having never received a doctorate. This might explain his often-deferential tone in correspondence with Cone when it comes to academic matters.

Cone and Deloria first met while the former was giving a lecture in Denver. During the question-and-answer portion of the program, Vine Deloria stood up and asked the question “What does all this have to do with Indians?”[6] Cone was stumped. After further conversation, the two continued their discussion over catfish in the Deloria kitchen. In the first letter from their voluminous correspondence, dating from March 1976, Cone thanks Deloria: “By the way, you wrapped the fish so well that I was able to bring it back to N.Y. and Rose, my wife, and children just loved it. They send their thanks.”[7] The friendship, collaboration, and letters would continue until Deloria’s death in 2005.

Both Deloria and Cone were giants in their respective fields. They also realized this about themselves and each other. One scholar commented to me that “Everyone sort of has their own personal Vine.” Similar stories were offered about Cone. It is perhaps not surprising then, that while I have heard from several scholars who knew Deloria intimately that he was publicly contemptuous of liberation theology, he wrote to Cone in 1979 apologizing for misunderstanding what liberation theology was: “I thought you had to be a Marxist.”[8] In some essays, Deloria even refers to himself as a Liberation theologian. Towards the end of his life, Deloria wrote that “The bitterness of reflection, these days, dwells not on what was accomplished but on what could have been accomplished had men been reasonable, just, or even consistent with themselves.” In Cone, he had found an intellectual fellow traveler who fulfilled these criteria. In another letter, he refers to both men as “people of the drum” up against and perhaps in conflict with the Western “people of the lyre.”[9]

Deloria then, somewhat confusingly, explains that he does believe that “the message of Christianity can’t be repeated enough… it does take the edge off the Anglo-Saxon Germanic desire to destroy.”[10] Meanwhile, he was publicly contemptuous of all christianity. Despite these claims to have “joined the pagans and heathens gathering in the hills,” Deloria had been ordained in the Episcopal Church after theological training, came from a long familial tradition of the priesthood, and continued in conversations with christians of nearly innumerable stripes.[11] Indeed, his father, Fr. Vine Deloria, Sr. was not only present at the 1983 Princeton conference, but offered an opening invocation and a closing benediction. Warrior comments that “The church had wounded him, but he kept going back, at least in certain ways because of his family and feeling bound by prophecy.”[12]

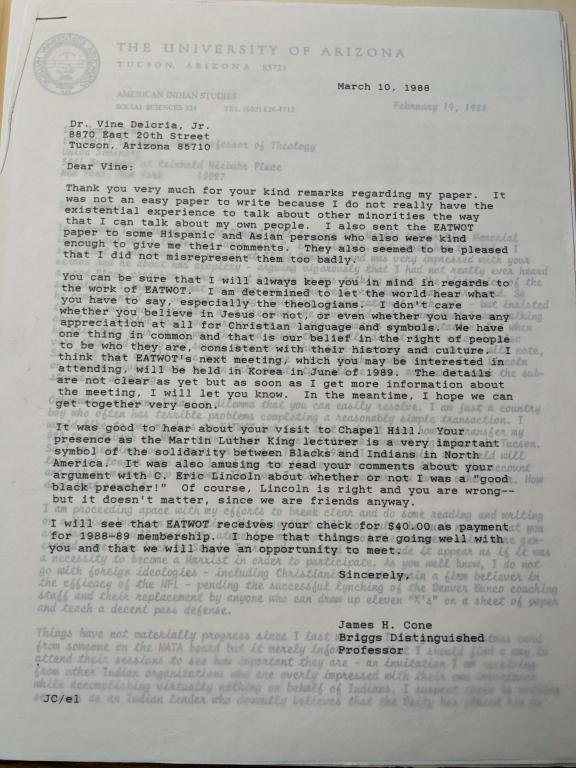

Additionally, one of the very few side-by-side comparisons of Cone and Deloria’s works I have been able to find in secondary literature comes in an essay by the Black scholar of religion, Charles Long, who argues quite critically that theology as a discipline is inappropriate for both Native and Black liberation. It becomes clear there are a series of critiques which we must make sense of. There is the critique Cone and Deloria level against White christianity, Deloria’s critique against religion writ large, the critique against theology, and critiques of these outside critics against Cone and Deloria. Cone and Deloria each clearly felt a debt to and a need to defend the other. In a September, 1988 letter to Cone, Deloria writes “Thanks of course to your career and leadership I have been able to get my intellectual ship on course and have been seriously thinking about what should be written from an Indian perspective on Liberation.”[13] In response, Cone wrote to Deloria “I am determined to let the world hear what you have to say, especially the theologians.”[14]

Helpfully, Cone describes for us what both systematic and liberation theology are. In a memoir published posthumously, he defines the field as “Theology is not philosophy…Theology is symbolic language, language about the imagination, which seeks to comprehend what is beyond comprehension. Theology is not antirational but it is nonrational, transcending the realm of rational discourse.”[15] Cone’s particular innovation was reading and constructing theology particularly as a Black man. As he puts it, “God must be with us because he was with Christ on the Cross. Even as we are lynched, God is beside us.”[16] Black Liberation Theology as he defined it focused on three themes in the christian scriptures and then married these themes to the experience of Black Americans. They are the Exodus or liberation of the Jews from Egypt, the Hebrew prophets’ emphasis on God’s solidarity with the poor, and Jesus’ description of his ministry as focusing on liberation. Cone further argued that “If the gospel is a gospel of liberation for the oppressed, then Jesus is where the oppressed are…If perchance, he is not in the ghetto, if he is not where men are living at the brink of existence, but is rather in the easy life of the suburb, then he lied and Christianity is a mistake.”[17] It should come as no surprise then that Cone and Deloria found common cause in questioning the veracity and helpfulness of easy, white christianity.

These themes have also been articulated by liberation theologians across the non-Western world and would also immerge amongst Native American Liberation Theology, which Deloria touched on and others have continued. Gustavo Guitierrez (A Peruvian theologian, largely credited alongside Cone as an originator of the broader category of liberation theology), Cone, and Deloria are all participants in a 1999 volume on American Liberation Theologies.[18] This volume also includes contributions from such luminaries as Cesar Chavez, Fr. Greg Boyle, and Delores Williams. Here we see Deloria at, in certain respects, his most pro-christian. In his essay, titled “Vision and Community, a Native American Voice,” Deloria argues that “we can glimpse a vision of community through the praxis of that liberation theology asks and demands of us.”[19] This praxis was precisely the preferential treatment liberation theology offered to the subaltern. It would also form the basis of a method for Cone’s Native students.

Cone and Deloria’s correspondence is the genre of the letter at its best and most colorful. Their letters are peppered with Biblical allusions, NFL allusions, and references to classic literature as well as their disgust with contemporary political figures, most especially Ronald Reagan. Deloria often references professional football as his true religion, even more than Lakota traditions. The humor at work between them also helps the friendship come to life before the reader’s eyes. In a letter from November 1992, Deloria opens “Well, I expected no less from an avowed Christian than a total forgiveness and I am glad I have that in hand.”[20]

Next month, I’ll most likely continue the story. For now, here’s the very first letter I found between the two. Its warmth excited me and suggested there was much more to come.

[1] Vine Deloria Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Correspondence box 119

[2] Vine Deloria Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Box 49, file Indian Theology and Law, Princeton

[3] Ibid.

[4] (Cone, Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody: The Making of a Black Theologian 2018) 64, (Cone, Risks of Faith: The Emergence of a Black Theology of Liberation 2005) xi ff

[5] (Cone, Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody: The Making of a Black Theologian 2018) 33ff

[6] Warrior describes hearing this story from both Cone and Deloria. Weaver heard it from Cone. It is also referenced throughout the Deloria/Cone correspondence. Robert Warrior, “Video: The Impact of God Is Red on Theology: Women’s Studies in Religion Program,” Harvard University, August 11, 2022, https://wsrp.hds.harvard.edu/news/2022/11/08/video-impact-god-red-theology-4.

[7] Vine Deloria Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. box 129, file James Cone

[8] James Hal Cone papers, box 44, file 17

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Following theologian George Tinker (Osage) I capitalize “White” while leaving “christianity” and several other terms lower case. Tinker explains this move “using the lower case christian or biblical allows us to avoid any unnecessary normativizing or universalizing of the principal institutional religious quotient of the Euro-west… Paradoxically, I insist on capitalizing the W in White (adjective or noun) to indicate a clear cultural pattern invested in Whiteness that is all too often overlooked or even denied by American Whites.”

[12] Interview with the author. This prophecy was given by a Deloria ancestor who determined that the family’s lives would be intertwined with christianity and particularly the Episcopal church. It was in duty to this prophecy that Vine Deloria Sr. became a priest instead of a football player. (P. J. Deloria 2004) Deloria interprets the vision/prophecy of his ancestor as such: “Had he chosen it, the left-hand road with the four skeletons would have meant that Saswe would have four generations of prosperous descendants, but the people following him would be no more than skeletons with flesh who would contribute virtually nothing to the world. It would have been a safe but completely nondescript family that nonetheless would have luck and would prosper. The red road was fraught with danger but filled with life. The four purification tents meant that Saswe would kill four men of his own tribe and have to undergo four purification rituals. He would have great powers as a medicine man, the Thunders would be his close

friends, and many birds and animals would help him. He was given a special stone to make it rain.” (Deloria Jr. 2000) (Hoffman 2009) 104

[13] Vine Deloria Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. box 129, file James Cone.

[14] Ibid.

[15] (Cone, Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody: The Making of a Black Theologian 2018) 67ff

[16] Ibid. p 127-129, 131

[17] (Cone, Risks of Faith: The Emergence of a Black Theology of Liberation 2005) 9ff

[18] (Peter-Raoul, Forcey and Hunter 1990)

[19] Ibid. 79

[20] Vine Deloria Papers. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. box 49 folder James Cone