Should those of us who work on religious history, particularly Christian texts from the past, consider publishing devotional as well as scholarly editions of our work?

Friars Quarters and Conference Meeting Rooms, Mission Santa Barbara

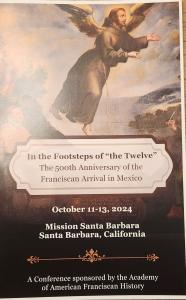

This is a question I asked myself last weekend during “‘In the Footsteps of “the Twelve’: The 500th Anniversary of the Franciscan Arrival in Mexico,” a conference at Mission Santa Barbara sponsored by the Academy of American Franciscan History, a research institute affiliated with the Franciscan School of Theology in Oceanside, California. After staying off the conference circuit to homeschool, the conference was a lovely reunion of friends old and new. AAFH Director Dr. Jeffrey Burns, in addition to being a Church historian and Archivist at the Chancery Archives for the Archdiocese of San Francisco, was my professor at the St. Ignatius Institute Great Books Program at the University of San Francisco back in the 90’s. Several Franciscan friars were in attendance, many of them members of the AAFH Board. What a delight to discuss Franciscan history at a Franciscan mission with Franciscans in our midst.

Program Cover of “‘In the Footsteps of “the Twelve’: The 500th Anniversary of the Franciscan Arrival in Mexico,” a conference at Mission Santa Barbara sponsored by the Academy of American Franciscan History

The opening keynote on Friday night, “The Franciscan Invention of the New World? New Directions in the History of Franciscans in the Americas,” from Julia McClure, a global historian from University of Glasgow, set the tone for the conference, prompting an animated discussion that spilled over into the opening reception.

Saturday brought many wonderful presentations: about Franciscans who recorded miraculous occurrences à la Little Flowers of St. Francis whenever criticisms of their work in colonial Mexico surfaced, about friars using games to teach (more on this below), and a project tracing diversity in the California missions. We also heard about Kivas in Franciscan missions in New Mexico, indigenous art in Franciscan friaries in 16th century Mexico, the Franciscan-educated indigenous boy martyrs of Tlaxcala, Dominicans using Franciscan histories, Franciscan Commissary-Prefects, and about a colonial transportation revolution and the Franciscan Mission system in California.

I’d like to highlight one presentation: “The Franciscans’ Playcentric Approach to Teaching Indigenous Children in the Americas” by historian Jonathan Truitt from Central Michigan University and Director of the Center for Learning through Games and Simulations. I’ve cited his book, Sustaining the Divine in Mexico Tenochtitlan: Nahuas and Catholicism, 1523-1700 several times in past blog posts. Truitt opened by quoting fray Jerónimo de Mendieta’s 1596 Historia Ecclesiastica Indiana (History of the Indian Church) declaring that God put it in the hearts of the first friars in Mexico that they should become childlike, setting aside solemnity. He told us that Hernando Cortés had outlawed the importation of games to New Spain after his gaming table was struck by lightning(!), so colonists carved their own dice and made their own cards. Inspired by Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas who understood games as a useful educational tool, early modern Europeans designed cards to represent Justinian’s code, to teach geography, and to teach rhetoric, the latter being so successful that the game maker was accused of witchcraft! The Church condemned the parlor games that emerged in Italy not in and of themselves, but because of what people *did* as they played.

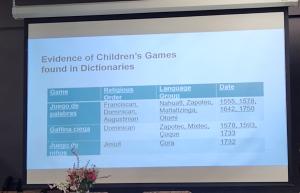

The Franciscans who arrived to Mexico in the 1520s were part of this tradition of education-based learning. To that end, Truitt shared a list of children’s games appearing in New World dictionaries from the 16th through 18th centuries, including Gallina Ciega (Blind Hen, aka, Blind Man’s Bluff). Dating back to the ancient Greeks, Gallina Ciega appeared in Mexico by the 1570s; the Franciscans introduced chess as early as 1555. To impress upon us the difficulty of introducing a game when neither knows the other’s language, Truitt paired us off and handed a slip of paper to one person with instructions, allowing 7 minutes to teach a game to one’s partner – using only sounds or made-up words.

Truitt explaining his game experiment

I turned expectantly to the scholar beside me, a young man from San Diego, who smiled, studied the sheet, then began gesticulating, repeating Shmee, Shmo, Shmu as he made three different signs with his hands, then pointed to me and grunted. Eventually, I came to understand that I must make each sign/sound. My partner then cycled through two signs – one with each hand – showing me which sign/sound conquered the other. Once I understood, he indicated that I was to make one of the three signs/sounds at the same time he did, and thus we began playing a game together, which I came to understand was a form of Ro, Sham, Bo. What an effective use of 7 minutes! Truitt took us back to that historical moment with the friars and the Nahuas, asking us to imagine explaining the rules of chess.

Saturday night’s collaborative keynote inspired the question with which I opened this post. John F. Schwaller, Professor Emeritus at the University of Albany, Editor of the Americas, and former Director of the Academy of American Franciscan History opened by discussing the development of Nahuatl-language devotional texts in colonial Mexico penned by friars or co-written by Franciscans and their tri-lingual (Nahuatl, Castilian, Latin) Nahua students. One text Schwaller mentioned, fray Alonso de Molina’s 1577 Nahuatl translation (with some Latin) of St. Bonaventure’s Life of Francis, he is currently translating with a team of interdisciplinary scholars. Mentioning the Reformation’s influence on art produced in colonial Mexico such as the deposition of Christ from the cross, Schwaller handed the floor to historian Mark Christensen from Brigham Young University, a specialist in Nahua and Maya Christianities, who discussed another genre of devotional text: performative sermons, i.e., as the priest speaks his sermon, Nahua actors perform his words. Stage directions guide the action.

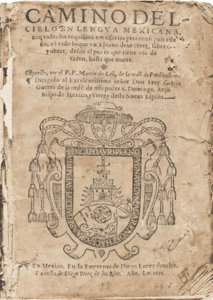

Frontispiece of fray Martín de León’s 1611 Camino del cielo en lengua Mexicana:

Christensen shared his current project: a translation of a performative sermon about the Deposition in Dominican fray Martín de León’s 1611 Camino del cielo en lengua Mexicana: con todos los requisitos necessarios para conseguir este fin, co[n] todo lo que vn [Christ]iano deue creer, saber, y obrar, desde el punto que tiene vso de razon, hasta que muere (The Road to Heaven in the Mexican Language: with everything necessary to reach this end, with all that a Christian should believe, know, and act from the age of reason to death); despite the Spanish title, the text is in Nahuatl, which would have been reviewed by a Nahua scholar. After giving us examples of the beautiful way certain words had been translated – apostles as “the agents of your precious child” and “they who were shaping him, his beloved” and the Virgin Mary as “precious noblewoman,” “precious-honored mother,” and “Our sorrowing mother,” Christensen proceeded to read a selection of the text. The language, added character (Ctesiphon whom Christ cured of blindness), and additional implements (ladder, pliers, shroud, tomb) provide insight into Nahua understandings of Christianity and ultimately, further reveal the uniqueness of Nahua Catholicism.

Mark Christensen introducing fray Martín de León’s Deposition in Nahuatl

Because this is an active project, I will share only a flavor of it here:

[Mary via the orator]

O wretched sin, o you disobedient. How could you throw my precious child to the ground? You relieved the light of my eyes. Where will I go? What will I do? Who will console me here on earth? I lost my consoler, but he remains next to me so that I can bury him. Who will help me? How can I lower him even if I had one who really dared to take him without the permission of Pilate?

[To Mary]

O precious noblewoman, may you not be very sad…. [God] already knows what is necessary for you: a wooden ladder, hammer, pliers, a cloak to wrap him in, and a death cave where you can bury him…

[To the audience]

Joseph and Nicodemus have arrived, they bring what is necessary to lower him down and bury him.

As Christensen read about the moment Christ’s sacred body came off the cross, I felt myself moved in a way I have never before been moved while listening to an academic paper. I was reminded of the closeness I felt to Christ while in the hospital on Holy Week, subject of a previous post [link]. During the Q & A I asked Mark whether in addition to a scholarly edition, he had considered releasing his translation as a devotional text, which I could imagine myself praying at church during Holy Week. Though he said he had not, afterwards he told me how much he appreciated my question, saying he would give it some more thought. I hope that he does publish a devotional version, for not only would modern-day Christians benefit from seeing our faith through the eyes of Nahua Christians, but praying with native peoples – even if separated by time and space – will change our (mis)understanding of native peoples of the Americas.

So I ask again, should those of us who work on religious history, particularly Christian texts from the past, consider publishing devotional as well as scholarly editions of our work?