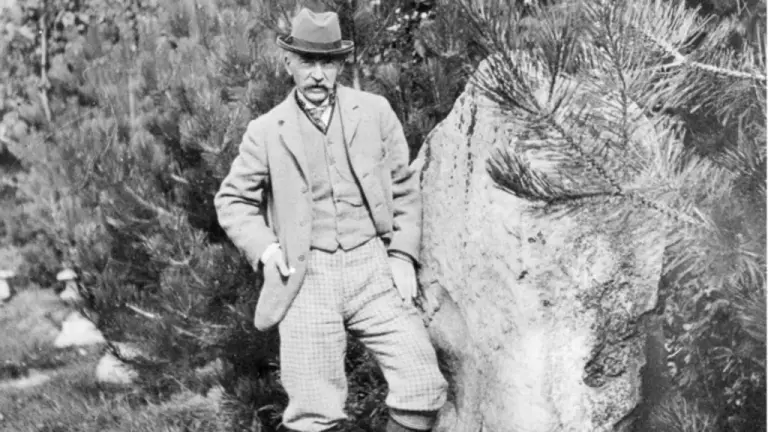

The category of folk horror was first identified in the 1970s, and in recent years it has generated a huge amount of media and critical attention. It is also the subject of a book I am working on presently. (See the major bibliography I offer here). Much of the early discussion focuses on cinema, and such classic 1970s films as The Wicker Man. But in fact, those productions were only the latest in a very long sequence of novels and literary works, which dated back into the late nineteenth century. In today’s post, very much intended for Halloween, I propose a candidate for the founder of the whole genre. If he did not actually write horror stories as such, then basically nothing that appears in the later novels and films is missing from the work of Thomas Hardy (1840-1928).

And as I will show, a very recent news story – just from last month! – makes this linkage even more totally appropriate.

I will just add that I have another highly seasonal Halloween post over at today’s Current magazine, on stone circles.

What is Folk Horror?

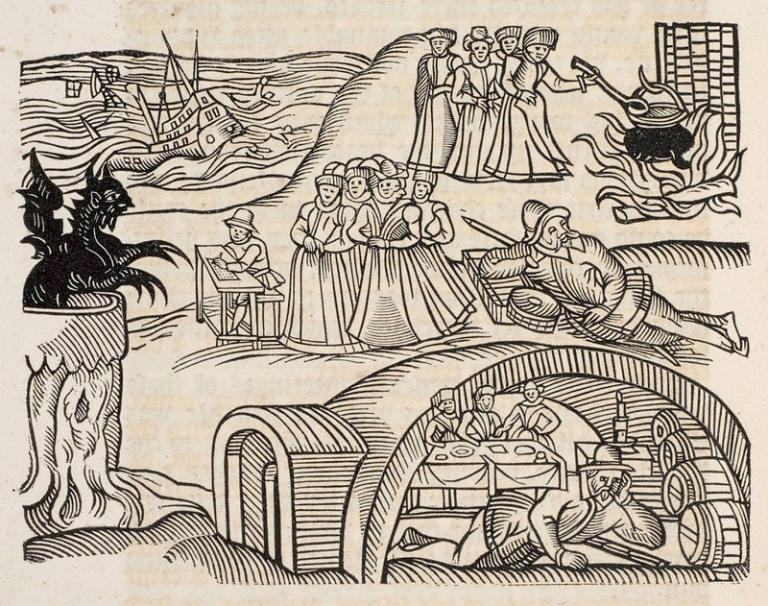

Folk horror is grounded in the idea that potent ancient forces and deep-rooted evils survive in the landscape, scarcely acknowledged by the modern world. In isolated communities, active witches or pagan groups mobilize those dark forces, deploying rituals dating from pre-Christian times. Think The Wicker Man.

Definitions of folk horror abound, but my own working model might be summarized as involving a “Three R” structure, of rural, recovery, and religious. If not essential, a rural or village setting is probable, or at least the suggestion that a modern environment is superimposed upon such a primordial landscape. Modern characters might for instance find that their familiar landscape was an overlay built upon an old pagan grove or temple.

Still more central is the theme of return or recovery, in the sense that ancient and primitive forces are found in that landscape and its inhabitants, and that they will manifest anew in the modern world. Such a return might happen in the form of ghosts or demonic figures, or else through the conscious revival of older ways by modern cults or devotees. Commonly, not necessarily, those “revivalists” are presented as witches or members of pagan movements. Modern people encounter aberrant forces or movements that have always existed in a particular locale, but in a clandestine way, until they are discovered anew. The motifs of return and discovery alike allow moderns to begin a sequence of encounters that will likely prove disastrous.

Beyond “rural” and “recovery,” the resurgent forces have some religious, spiritual, or otherwise supernatural dimension. It is not sufficient that they merely represent violence or sexual excess, unless that is channeled in those ritualistic and religious-directed forms.

If we apply that model to the British context, we see how naturally and intuitively writers or artists could imagine the coalescence of the three elements, in a way that made the rise of some kind of “folk horror” all but inevitable. We think especially of the megalithic monuments that are such a visible feature of the pre-modern landscape. The world-famous stone circle of Stonehenge has many local counterparts, besides stone tombs, barrows, and earthworks. The religious or spiritual nature of such places is a natural deduction, but least from the seventeenth century, a large corpus of speculative writing associated their construction with the druids, who were described at length by Classical authors such as Julius Caesar (However widely credited, that attribution was around two thousand years too late). That druidic context encouraged the view of stone circles not just as temples of a bygone religion, but also of human sacrifice, possibly on a large scale. From that perspective, to contemplate the British landscape was to inspire thoughts of its buried horrors, a bygone fanaticism devoted to forgotten gods, and it did not take too much imagination to think of such ghosts returning to haunt a modern world. The resulting fictions almost wrote themselves. The wicker man figure that gave its title to the 1973 film was taken directly from Caesar’s accounts of the British druids.

So think of a rural landscape with its ancient monuments, look at the ancient and likely lethal forces that once resided there, and imagine them returning in some form to the modern day world. The story writes itself.

Hardy’s Pagan Worlds

One surprisingly early advocate of ideas of pagan remnants and survivals was Thomas Hardy. Several of his novels offered rich portrayals of the rural society he had known during his mid-century childhood, a world that revolved around seasonal rituals, with their attendant folk customs. In describing these, Hardt often drew attention to their pagan origins, and their associations with ancient features of the landscape, Roman or prehistoric. Because Hardy was such a very standard and canonical author through the twentieth century, and was so often represented in school curricula, his portrait of the pagan countryside reached a very wide audience. Reinforcing that impact were the very frequent adaptations of the individual novels, in film, television, theater, and radio. In 1973, even Monty Python featured a sketch of Hardy writing his novel The Return of the Native (1878). The books are (or were) that well known.

Hardy’s work offered a primer in folk horror. The Return of the Native itself begins with the country dwellers on Egdon Heath building their November bonfires which were notionally intended to commemorate Guy Fawkes’s Day, but which also marked the age-old celebration of the start of the Winter season. The country dwellers gather around an old Celtic/British barrow, where Hardy suggests that an observer might almost see the shade of one of the ancient builders. Hardy places the ritual fires in a historical trajectory dating back millennia, suggesting that ancient paganism was lurking only barely below the surface:

It was as if these men and boys had suddenly dived into past ages, and fetched therefrom an hour and deed which had before been familiar with this spot. The ashes of the original British pyre which blazed from that summit lay fresh and undisturbed in the barrow beneath their tread. The flames from funeral piles long ago kindled there had shone down upon the lowlands as these were shining now. Festival fires to Thor and Woden had followed on the same ground and duly had their day. Indeed, it is pretty well known that such blazes as this the heathmen were now enjoying are rather the lineal descendants from jumbled druidical rites and Saxon ceremonies than the invention of popular feeling about Gunpowder Plot.

Reporting the local women decorating a Maypole, Hardy remarks that

The instincts of merry England lingered on here with exceptional vitality, and the symbolic customs which tradition has attached to each season of the year were yet a reality on Egdon. Indeed, the impulses of all such outlandish hamlets are pagan still—in these spots homage to nature, self-adoration, frantic gaieties, fragments of Teutonic rites to divinities whose names are forgotten, seem in some way or other to have survived mediaeval doctrine [that is, Christianity].

Here, the past is never truly past. When the hero walks the heath alone,

the past seized upon him with its shadowy hand, and held him there to listen to its tale. His imagination would then people the spot with its ancient inhabitants—forgotten Celtic tribes trod their tracks about him, and he could almost live among them, look in their faces, and see them standing beside the barrows which swelled around, untouched and perfect as at the time of their erection.

It is “as if” those ancient dwellers were walking around him – but we would not have to travel very far indeed to imagine them actually returning in some way, to assail or curse the present. We are on the verge of full-fledged folk horror.

Tess’s Sacrifice

In 1891, Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles tells the story of a village girl who is seduced by a wealthy neighbor, whom she eventually kills (The book appeared in a single volume the following year). By no standard could the book be categorized as horror and still less folk horror, but the pagan context is pervasive, even in this late Victorian setting. Echoing his earlier comments, Hardy remarks that, the countryside around Tess’s village was once densely wooded: “The forests have departed, but some old customs of their shades remain. Many, however, linger only in a metamorphosed or disguised form.” The book begins with the heroine marching in a Spring event for village women that Hardy sees as a modern-day continuation of an ancient May Day pagan rite, the Roman fertility festival of the grain goddess Ceres. The women’s club “lived to uphold the local Cerealia. It had walked for hundreds of years, if not as benefit-club, as votive sisterhood of some sort; and it walked still.”

Hardy even applies the loaded word “fetish,” a term originally applied to African idols, the study of which had become a mainstay of the academic anthropology of the time. When Tess sings the Christian Canticle of the Benedicite, with its invocation of the forces of Nature, Hardy calls it

a Fetishistic utterance in a Monotheistic setting; women whose chief companions are the forms and forces of outdoor Nature retain in their souls far more of the Pagan fantasy of their remote forefathers than of the systematized religion taught their race at later date.

Early in the book, we encounter hints of older sacrifices. When Tess first visits the great house of the man who would seduce her, the author remarks that it stood near “a truly venerable tract of forest land, one of the few remaining woodlands in England of undoubted primaeval date, wherein druidical mistletoe was still found on aged oaks.” At the time, referring to druids certainly implied human sacrifice.

The novel ends with Tess facing capture and death within Stonehenge, effectively as a sacrifice to the pagan gods – arguably, as a personification of Nature. When Tess herself seeks rest, she literally lies on a sacrificial stone altar: “The eastward pillars and their architraves stood up blackly against the light, and the great flame-shaped Sun-stone beyond them; and the Stone of Sacrifice midway.” That sacrificial image would influence feminist writers over the following decades. Stonehenge itself has also featured in some of the novel’s many film versions.

Of Witches and Woodlanders

Hardy made much use of pagan and occult material to suggest the thoroughly non- and pre-Christian spiritual underworlds of the Victorian countryside. The conflict between the two main women characters in The Return of the Native is fought out through charges of witchcraft, with Eustacia Vye characterized as the Queen of the Night, with “pagan eyes, full of nocturnal mysteries.” Seeking to defend herself, Susan Nunsuch attacks Eustacia by melting a wax effigy of her while reciting the Lord’s Prayer backwards.

Hardy’s short story “The Withered Arm” (1888) is another a classic story of rural witchcraft. Despite its contemporary setting, the tale describes a situation which would have occurred widely in earlier eras, when it would likely have ignited a full-scale witchcraft panic. In a dream, a woman unintentionally casts an effective spell on a neighbor. The situation can only be resolved by consulting a local conjuror, who explains the ritual magic she will need, namely touching the neck of a hanged man.

But it was in his novel The Woodlanders (1887) that Hardy delved deepest into pagan ideas, thoroughly rooted in the English countryside. The book follows the cycles of the year in a village dominated by its apple orchards, with all the pagan-looking ceremonies attached to different seasons of the year. The local people are “woodlanders” in the sense of being as integral to the wooded landscapes as are the trees themselves. The character Giles Winterborne is frankly described as an incarnation of a pagan deity, the spirit of the Fruit:

He looked and smelt like Autumn’s very brother, his face being sunburnt to wheat-color, his eyes blue as corn-flowers, his boots and leggings dyed with fruit-stains, his hands clammy with the sweet juice of apples, his hat sprinkled with pips, and everywhere about him that atmosphere of cider which at its first return each season has such an indescribable fascination for those who have been born and bred among the orchards. ….. He rose upon her memory as the fruit-god and the wood-god in alternation; sometimes leafy, and smeared with green lichen, as she had seen him among the sappy boughs of the plantations; sometimes cider-stained, and with apple-pips in the hair of his arms, as she had met him on his return from cider-making in White Hart Vale, with his vats and presses beside him.

This reads uncannily like the portraits that Sir James Frazer would offer in his vastly influential book The Golden Bough (1890), of the human manifestations of Nature spirits. Frazer also argued that that belief was inextricably connected to human sacrifice. A human being, a king, personified the Nature spirit, and when he became old and frail, he had to be killed and replaced to avoid the danger that the earth might lose its fertility. When Frazer’s book did appear, Hardy read him with much interest, but in this instance, it looks rather as if Hardy influenced Frazer, rather than the other way round. If it is no sense a work of horror, The Woodlanders is an authentically visionary pagan novel.

To What Green Altar?

Hardy has been dead for almost a century, so how on earth can I suggest that a recent news story might throw new light on his work, and its folk horror dimensions?

Well, it goes back to the 1880s when he was building his house, Max Gate in Dorchester, where ancient burial remains turned up during the process of construction. He also found a sarsen, a megalithic stone dating back several thousand years. Like most of his contemporaries, Hardy believed that this was the work of druids, and in one poem he refers to that standing stone in his garden as “the druid stone/That broods in the garden white and lone.” That association was heavily loaded, suggesting as it did the vestiges of human sacrifice.

It was only when excavations were carried out in the 1980s, before the construction of a road next to the house, that archaeologists discovered what else was under the soil: a large circular Neolithic enclosure, or “proto-henge”, almost 100 metres in diameter, that was built in about 3,000BC, or about the same time as the circular earth bank that today surrounds Stonehenge’s stone circles, the earliest phase of the monument….

When he was writing the climax of Tess of the Durbervilles, with its scene at Stonehenge, Hardy “was sitting right in the heart of a large henge-like enclosure that was even older than the famous monument on Salisbury Plain.” It was literally right under him. Last month, that “Dorset Stonehenge” received protected status, and hence the news story.

Oh, what Hardy could have done with that, had he known.

I won’t single out much from the folk horror bibliography I mentioned earlier, but do see Alan G. Smith, Robert Edgar, and John Marland, Thomas Hardy and the Folk Horror Tradition (New York: Bloomsbury, 2023). Lest it appear that I am just borrowing from that book, I note that I was posting on all this back several years previously!

There are plenty of other fine recent studies of Hardy and his world, by no means all on the themes that I discuss here. See particularly Paula Byrne, Hardy Women: Mothers, Sisters, Wives, Muses (London: William Collins, 2024).