After the recent horrors in New Orleans, we have heard a huge amount about lone wolf terrorism and self-radicalization, with many debates about when and whether a seemingly isolated act of extreme violence can properly be categorized as terrorism. I have been publishing and teaching on lone wolf terror at least as long as any other expert in the field – thirty years or so – and I have things to say on the topic that are still not widely recognized, particularly about where the concept came from in the first place. Some of the connections really are startling.

Apart from shorter magazine pieces, I discussed these matters at length in my 2003 book Images of Terror: What We Can and Can’t Know about Terrorism, and in later pieces. One of those in particular still makes me uneasy. In July 2016, I did a column for American Conservative on “Low Tech Terror” which warned of the then very new peril of terrorists using cars or trucks to slaughter innocent civilians. As I wrote, “On such occasions, a determined driver not afraid of being killed could easily claim twenty or more fatalities.” One week after that column appeared, a truck driver in Nice, France, did exactly that, killing over eighty. As I posted at Anxious Bench at that time, I truly, truly, hate being right.

I also know where that lone wolf idea came from, and the source is very surprising. I will here reproduce a column I did at RealClear Religion back in 2013. I will keep the text pretty much as it stood without doing any updating or editing. You will see that I refer to then-recent attacks like the Boston Marathon bombings. Note also that I am talking here about al-Qaeda not Islamic State, as I would have done had I been writing a bit later: IS actually originated as a Qaeda affiliate, al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). Nor do I reference the recent Jude Law film The Order. But the strictly contemporary relevance of the piece as it stands is obvious, I think.

That original column here follows:

Anwar al-Awlaki’s Nazi Roots

Western governments dread large-scale terror attacks that might repeat the horrors of 9/11, or of subsequent atrocities in London, Madrid, Mumbai and elsewhere.

In theory, though, such assaults should now be fairly easy to prevent. Modern means of surveillance make it extraordinarily difficult for terror groups to keep their operations secret for months or years at a time, to handle complex logistics without drawing attention. In consequence, al Qaeda and related Islamist movements have in recent years shifted their focus to smaller-scale acts carried out by lone individuals or very small cells of two or so people, which are very difficult indeed to detect in advance.

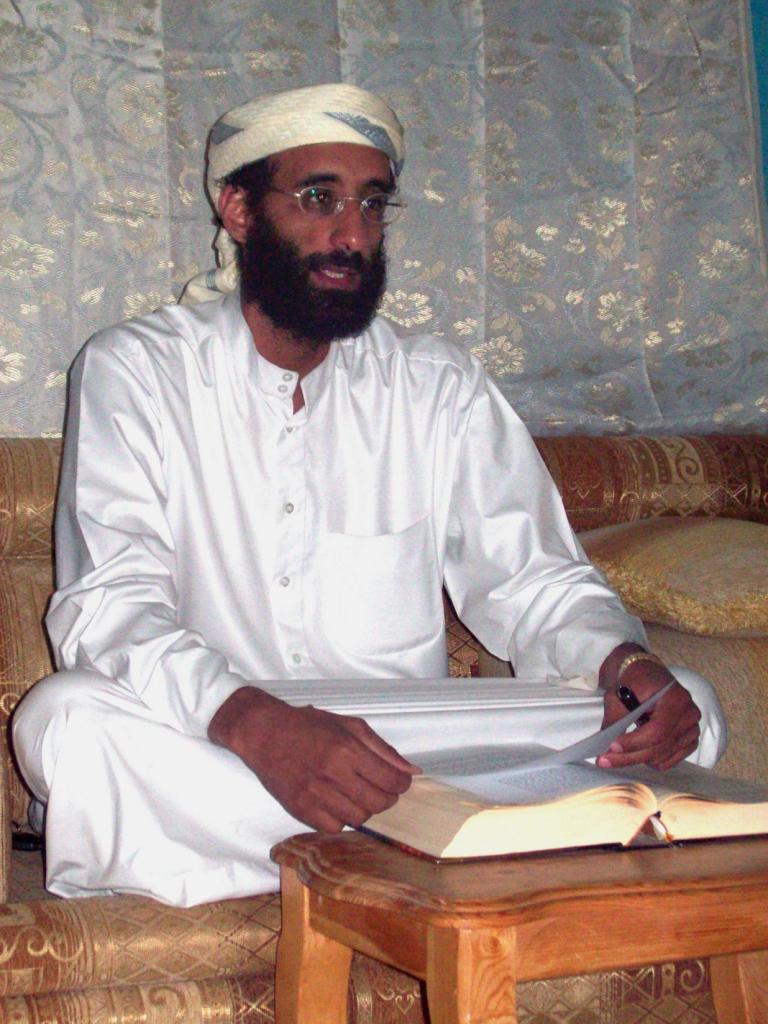

We think of the attacks at Fort Hood, at the Boston Marathon, and the recent beheading of a soldier in London. Yemeni-American Qaeda leader Anwar al-Awlaki (now, happily, deceased) used the Internet to propagate a whole instruction manual for small groups and individual lone wolves seeking to create mayhem while avoiding detection.

When I hear of such assaults, I feel a strange sense of déja vu. Although the present terror wave undoubtedly grows out of the extreme Islamist world, it precisely reproduces theories that originated in very different circumstances, and in fact, in the United States itself. Amazingly, these ideas surfaced not in a Muslim context, but rather grew out of the neo-Nazi White Supremacist Right.

The key figure was American neo-Nazi leader William L. Pierce (1933-2002). Although Pierce spent decades trying to organize the nation’s diffuse menagerie of far Right groups, his most significant contribution was the 1975 novel The Turner Diaries, a terrorist manual for the overthrow of the United States government by a group called the Order. The Diaries supplies elaborate nuts and bolts descriptions: how to combine fuel oil and fertilizer to make a powerful bomb, how to sabotage the port of Houston, the best means of sabotaging a nuclear power plant (mortars firing nuclear contaminants).

The book reads like a manual for terrorist warfare, and some of its readers did indeed try to realize its lethally dark vision. Already in the mid-1980s, the text inspired a vicious campaign by a group based in the Pacific North West that actually took the name of “The Order,” and plotted to bring down the U.S. government by counterfeiting, bombing and assassination. The 1995 Oklahoma City bombing precisely followed the Diaries‘ detailed technical blueprint for the imaginary destruction of FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The real-life Order’s campaign failed miserably, and for obvious reasons. A terrorist leader may issue an order to plan some attack, but almost certainly, law enforcement will intercept it somewhere along the chain of command. Followers will be arrested and “turned,” persuaded to become informants within the organization. Soon, the group can do nothing without its every move being overheard by the FBI, who can intervene at will. New techniques of surveillance were reinforced by powerful legal weapons aimed against subversive conspiracies. By the late 1980s, the paramilitary far Right was in ruins.

Responding to crisis, extremist theorists evolved a shrewd if desperate strategy of “leaderless resistance,” based on what they called the “Phantom Cell or individual action.” If even the tightest of cell systems could be penetrated by federal agents, why have a hierarchical structure at all? Why have a chain of command? Why not simply move to a non-structure, in which individual groups circulate propaganda, manuals and broad suggestions for activities, which can be taken up or adapted according to need by particular groups or even individuals?

To quote far Right theorist Louis Beam, “Utilizing the leaderless resistance concept, all individuals and groups operate independently of each other, and never report to a central headquarters or single leader for direction or instruction…No-one need issue an order to anyone.” The strategy is almost perfect in that attacks can neither be predicted nor prevented, and that there are no ringleaders who can be prosecuted. The Internet offered the perfect means to disseminate information.

And that brings us back to William Pierce, who followed Turner Diaries with another book that provides a prophetic description of leaderless resistance in action. Hunter, published in 1989, portrays a lone terrorist named Oscar Yeager (German, Jäger) who assassinates mixed-race couples. The book is dedicated to Joseph Paul Franklin, “the Lone Hunter, who saw his duty as a white man, and did what a responsible son of his race must do.” Franklin, for the uninitiated, was a racist assassin who launched a private three year war in the late 1970s, in which he murdered interracial couples and bombed synagogues. The fictional Yeager likewise launches armed attacks against the liberal media, and against groups attempting to foster good relations among different races and creeds.

Central to the book is the notion of revolutionary contagion. Although the hero (for hero he is meant to be) cannot by himself bring down the government or the society that he detests, his “commando raids” serve as a detonator, to inspire other individuals or small groups by his example. “Very few men were capable of operating a pirate broadcasting station or carrying out an aerial bombing raid on the Capitol, but many could shoot down a miscegenating couple on the street.” He aimed at the creation of a never-ending cycle of “lone hunters,” berserkers prepared to sacrifice their lives in order to destroy a society they believe to be wholly evil.

Had Pierce’s blueprint been followed, the result would have been an entirely unprecedented terrorist campaign, combining the devastating effects of traditional clandestine warfare with an immunity to essentially all existing counter-terrorist methods. This new form of terrorism would have differed as much from the classic model as the electronic battlefield of modern warfare does from Gettysburg.

Politically, the US ultra-Right was too weak in the 1990s to follow Pierce’s model, and the movement never fully recovered from Oklahoma City. But the Hunter tactics live on, precisely, in the modern Islamist world, and specifically in the influence of Anwar al-Awlaki. Reading texts from al Qaeda’s online magazine Inspire, we so often hear what sound like direct echoes of Pierce.

So close are the parallels in fact that I wonder about a direct link, most likely through al-Awlaki himself, who spent the 1990s in the US. Obviously, he would have had no sympathy for White Supremacist theories, but he might well have encountered related materials almost by accident. We know that in the 1990s, he was being drawn to radical Islamism, and supported armed resistance in Chechnya and elsewhere.

I am speculating here, but I offer a possible interpretation. In the United States, al-Awlaki would have had easy access to the rich array of paramilitary books and manuals circulated by far Right and survivalist mail order firms, which also sold anti-Semitic tracts. Both kinds of writing would have appealed to a budding jihadi. If he dabbled at all in this subculture, he would very soon have encountered the books of Pierce, who was a best-seller in these catalogues. Particularly in the early nineties, Hunter was the hottest name in this literary underworld. If not Hunter itself, al-Awlaki would certainly have heard discussions of leaderless resistance, which was all the rage on the paramilitary Right in those years.

It would be a strange irony if ideas developed to promote White Supremacy were borrowed so successfully by the deadliest enemies of Euro-American civilization. Somewhere, William Pierce’s ghost is not amused.