It’s March, which means it’s Women’s History Month– and while in past years at the Anxious Bench, my March posts have been more celebratory, this year’s post is a bit different. Past posts have pointed out how doing church history with an eye towards women tells a better story of the church, or why having women at the table when making policies matters. This year, I’m writing about two books that I think everyone should read this March (one that’s been out a while and one that comes out on March 18). These are hard but important reads, books that should push us first towards contemplation of our systems and structures and how we use them and then towards action within our communities.

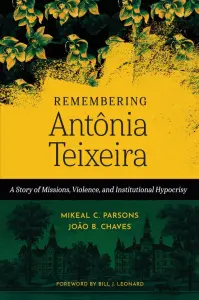

The first of these two books came out in 2023 and sat on my bookshelf for a while until I picked it up this fall: Remembering Antônia Teixeira: A Story of Missions, Violence, and Institutional Hypocrisy. Mikeal C. Parsons and João B. Chaves, the authors of this book, tell the story of Antônia Teixeira, the young daughter of a Baptist missionary in Brazil in the late nineteenth century. Her father, Antônio, was a controversial figure but played a central role in Baptist mission efforts in Brazil; his work put Antônia in close relationship with missionaries from the United States, who worked with Baylor’s president to enroll Antônia as a student at Baylor University in 1892. She paid for her tuition and living expenses through working as a servant in the household of Rufus and Georgia Burleson, the president and first lady of the university. While working in their household, in 1894, Antônia was assaulted by H. Steen Morris, a relative of the Burlesons. A series of trials– in courts, in newspapers, and in public opinion– took place over the rest of the 1890s, during which Antônia’s character, virtue, age, and account were constantly doubted, disparaged, or minimized. And as soon as possible, Antônia was forgotten, literally sent out of state to prevent any additional scandal– while the powerful men who had used the systems of courts and press to protect their own positions kept their homes, jobs, careers, and reputations. The careful archival work of Parsons and Chaves follows Antônia from Brazil to Texas and ultimately to Memphis, where she disappears from the record in 1896, seeking to remember and give voice to the story of a vulnerable young girl used and abused by powerful men.

The first of these two books came out in 2023 and sat on my bookshelf for a while until I picked it up this fall: Remembering Antônia Teixeira: A Story of Missions, Violence, and Institutional Hypocrisy. Mikeal C. Parsons and João B. Chaves, the authors of this book, tell the story of Antônia Teixeira, the young daughter of a Baptist missionary in Brazil in the late nineteenth century. Her father, Antônio, was a controversial figure but played a central role in Baptist mission efforts in Brazil; his work put Antônia in close relationship with missionaries from the United States, who worked with Baylor’s president to enroll Antônia as a student at Baylor University in 1892. She paid for her tuition and living expenses through working as a servant in the household of Rufus and Georgia Burleson, the president and first lady of the university. While working in their household, in 1894, Antônia was assaulted by H. Steen Morris, a relative of the Burlesons. A series of trials– in courts, in newspapers, and in public opinion– took place over the rest of the 1890s, during which Antônia’s character, virtue, age, and account were constantly doubted, disparaged, or minimized. And as soon as possible, Antônia was forgotten, literally sent out of state to prevent any additional scandal– while the powerful men who had used the systems of courts and press to protect their own positions kept their homes, jobs, careers, and reputations. The careful archival work of Parsons and Chaves follows Antônia from Brazil to Texas and ultimately to Memphis, where she disappears from the record in 1896, seeking to remember and give voice to the story of a vulnerable young girl used and abused by powerful men.

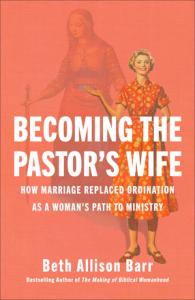

The second book, Beth Allison Barr’s forthcoming Becoming the Pastor’s Wife: How Marriage Replaced Ordination as a Woman’s Path to Ministry, might not at first glance seem to be closely related to Parsons’ and Chaves’ study of Baylor and Brazil in the 19th century. Barr’s book is not a focused study of a single individual or case, but instead a sweeping chronological survey of the shifting roles of women in the church from the early church to the present, showing how as definitions of ministry and ordination shifted, the expectations for women (and the spaces in which they were permitted to serve) shifted as well, culminating in the modern model of the pastor’s wife, an unpaid “bonus” ministry worker serving not as a formal member of church staff but as a part of her husband’s formal, paid ministry. However, when reading Ch. 8 of Barr’s book I couldn’t help but notice thematic resonances between the two works. In this chapter, Barr tells the story of Maria Acacia, a victim of abuse and an institutional coverup in the 20th century. The wife of a pastor and missionary, Maria and her family worked and served in Baptist missions efforts and churches in Switzerland, Italy, Canada, and the US. During their time in Toronto, her husband’s “affair” with a much younger congregant (a clear case of clergy sexual abuse) came to light– and then was covered up, as Maria’s husband Mario was allowed to resign his position and move to a new one in Washington, D.C.. Despite attempts from his former congregants in Toronto to have consequences brought against Mario Acacia for his unrepentant abuse and sin, Baptist leaders set aside and archived the letters of concern without taking action. Concerns for reputation again overcame concerns for vulnerable women.

The second book, Beth Allison Barr’s forthcoming Becoming the Pastor’s Wife: How Marriage Replaced Ordination as a Woman’s Path to Ministry, might not at first glance seem to be closely related to Parsons’ and Chaves’ study of Baylor and Brazil in the 19th century. Barr’s book is not a focused study of a single individual or case, but instead a sweeping chronological survey of the shifting roles of women in the church from the early church to the present, showing how as definitions of ministry and ordination shifted, the expectations for women (and the spaces in which they were permitted to serve) shifted as well, culminating in the modern model of the pastor’s wife, an unpaid “bonus” ministry worker serving not as a formal member of church staff but as a part of her husband’s formal, paid ministry. However, when reading Ch. 8 of Barr’s book I couldn’t help but notice thematic resonances between the two works. In this chapter, Barr tells the story of Maria Acacia, a victim of abuse and an institutional coverup in the 20th century. The wife of a pastor and missionary, Maria and her family worked and served in Baptist missions efforts and churches in Switzerland, Italy, Canada, and the US. During their time in Toronto, her husband’s “affair” with a much younger congregant (a clear case of clergy sexual abuse) came to light– and then was covered up, as Maria’s husband Mario was allowed to resign his position and move to a new one in Washington, D.C.. Despite attempts from his former congregants in Toronto to have consequences brought against Mario Acacia for his unrepentant abuse and sin, Baptist leaders set aside and archived the letters of concern without taking action. Concerns for reputation again overcame concerns for vulnerable women.

While Maria’s story fits into Barr’s book as part of a much larger story, the similarities in the narrative Barr traces about the rise of the pastor’s wife (and corresponding limitation of other roles in ministry for women) and the one Parsons and Chaves tell about missions and institutions are striking. Both books show how mobile and responsive large religious institutions can be when power and money are on the line. And both books show how systems and structures can be used as shields for the powerful, at the expense of people sacrificed in the name of money and influence. By looking at the stories of these women, Barr, Parsons, and Chaves compellingly show the perils of making the preservation of an institution more important than the theology that institution is supposed to support.

So, what actions do these books urge us to take? What lessons can we take from them? First, these books urge us to remember: to look for and listen to the voices of the vulnerable, both in history and in our present. Doing so is an act of Christian love that follows Christ’s command to love our neighbors. Second, these books show us that abuse is not always a problem stemming from individuals, but perhaps more often growing from systems and structures that focus on wealth and power. This focus often encourages a sort of moral apathy or blindness towards actions that betray the teachings of Christ, as long as the actions extend the institution’s influence or wealth. As historian Bill Leonard puts it in the introduction to Remembering Antônia Teixeira, the history of those abused by the church teaches us a “hard lesson”: “our claims of orthodoxy will not absolve us from the sins that can so easily beset us . . . our claims to ‘believe the Bible’ do not mean that we are incapable of ignoring the gospel.” (p. xi) The fact that these two books (spanning chronologically from the early church to the present) ultimately show such similar systems at work in first hiding or minimizing abuse and then hiding the stories of these women should convince even the most skeptical readers that the problem isn’t a few individual sinners, but systems and structures that prioritize anything over the gospel.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, these books show that systems and structures can be (and often are) changed to protect power, money, and status. Barr’s book compellingly shows how, so often, changes in practice or definitions are driven by perceived threats to power and money, like in the case of changing medieval regulations (Ch. 4) or shifting IRS tax laws (Ch. 7) on clergy. If we can change structures and systems to protect the powerful, we can change them to protect the vulnerable: but we have to be willing to stare our idols of influence and wealth right in the face and reject them in order to do so. To rebuild structures and systems and institutions as shields for the vulnerable rather than the powerful is to follow the heart of Christ’s teachings. On his podcast, Esau McCaulley recently noted that “Jesus’ way of being God, namely that he suffered and humbled himself, challenges the Romans’ understanding of strength and success and power.” This seems to be at the heart of the problems these books point out: religious systems and structures that reflect the values of the Romans rather than Christ reflect the power structures Christ subverted and calls us to likewise subvert. We cannot accomplish this systemic shift without returning to the first action these books encourage: without listening to those being hurt by current systems and structures and remembering what our priorities should be, not in line with the goals of the Romans but with the teachings of Christ. So, this March, let’s remember, lament, listen, and learn. Let’s stop using systems and structures as swords of oppression that shield abusers and instead remake them into shields for the vulnerable– no matter the financial cost.