There are years when everything seems to happen at once, years that shape conditions for decades to come. 1915 is one such, 1968 another – and as I have learned through writing a good many books, 1893 is another, and above all in matters of religion and spirituality. Now, I know what you are probably thinking here. 1893 is already very famous in such matters, as the time of the very influential World’s Parliament of Religions, held in Chicago, and that is the subject for a great many studies, general and specific. But that is only one small part of a much larger story.

Please note that this and all the images in this post are from wikipedia sites, and all are public domain

Please note that this and all the images in this post are from wikipedia sites, and all are public domain

When the World Changed

Let me make the case for 1893 as a critical turning point. If not the precise birthdate of modernity in US history, then that one year marks a crucial beginning in the American history of Biblical scholarship; of the clash between fundamentalism and Modernism in religion; of the Judeo-Christian encounter with Global Faiths; of feminist theory in religion; in anthropological understandings of Christianity; in theories of witchcraft as an authentic pagan survival; of critical developments in the history of women’s rights, and of the history of Temperance and Prohibition militancy; of scientific theories of race, religion, and intelligence; of a grimly decisive shift towards White Supremacy and racial segregation; of Black protests against that White Supremacy; of scientific studies of sexuality; of understandings of criminality and sexual deviancy, especially offenses committed against children; of American concepts of empire, with all the racial implications; of the American leap to Trans-Pacific power; and of so much else.

In so many of these individual topics, we find common overlapping cultural themes, including unprecedented globalization, surging interest in scientific approaches to race, a new sense of women’s role in the world, and a fascination with biology that encouraged determinism. The year marked a sweeping change in cultural consciousness.

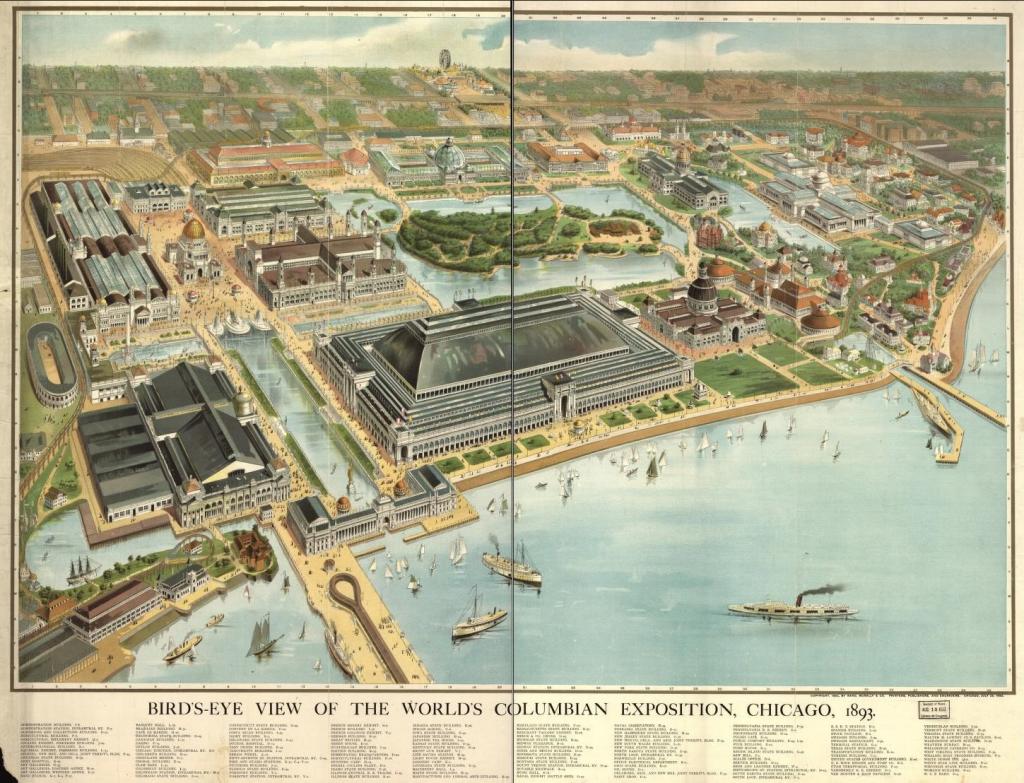

In matters of technology and business, too, the future was fast coming into view. Any account of the 1893 Exposition offers a canonical list of the discoveries and novelties that now gained popularity. The zipper naturally leads the list, followed by the Ferris Wheel, Aunt Jemima products, and the automatic dishwasher. But other developments were of far more consequence. The year brought America’s first company automobiles (Duryea, in Massachusetts). In New Jersey, Thomas Edison created the world’s first motion picture studio. Oh, the year also marks the first recorded college basketball game.

In standard American histories, 1893 stands out because that was the year when Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his famous paper proclaiming the death of the American frontier. We can agree with that argument or not as we wish, but assuredly, the closing of one geographical and cultural frontier coincided neatly with the opening of many others.

Evidently, no one date literally changed the world, and what we are really doing is seeing how those years served as focal points for much larger trends. But time and again, those special years do emerge as turning points. Any effort to focus on a single year raises obvious problems, of which I am keenly aware, and I want to state them upfront. No year or decade in itself has any kind of mystical quality, and there is a tendency to shoehorn dramatic events from nearby years into that one magical period, and to exaggerate their novelty and uniqueness. We might for instance take long term trends and find some tag that allows us to pin them down as if they were somehow new or unique to 1893, or 1968. It might also be that some special reason makes sources for some allegedly special year uniquely abundant or easy to find, and that is certainly the case in 1893. The Chicago World’s Fair attracted global interest, encouraging any ambitious writer or publisher to attach a project to the amazing event, and the amazing year. The Exposition in itself generated huge amounts of writing and speech-making, not to mention multiple ancillary events, such as the World’s Parliament of Religions. People knew they were living at an astonishing historical moment, and they responded by writing and speaking for the ages.

1893 as a Hinge Year

But even with all these caveats, 1893 still stands out, much like its counterpart years, such as 1968. Some of the events and publications that I will be discussing genuinely were unprecedented, and assuredly qualify for the R-word, revolutionary. In some instances, we are indeed looking at long term trends, but they accelerated so rapidly during 1893 that they seemed to have been created afresh. So dramatic were they, so innovative, that they took decades to play out, but time and again, we have to turn back to 1893 to understand them. Repeatedly too, 1893 is a pivot for trends that are often misleadingly located in other eras, such as the ever-popular 1898. In short, 1893 qualifies for my definition of a revolutionary era, namely that once it had been experienced, it was impossible to imagine realities as they had existed beforehand. It was not that people did not want to return to the prior era, but they could not: the world had changed too much.

In passing, that was also the era of some American writers I value greatly, and who offer terrific quotations to illustrate what I have to say: Mark Twain and William Dean Howells, of course, but also Harold Frederic, Kate Chopin, Robert W. Chambers, Stephen Crane, and George Washington Cable. And then there is Hamlin Garland, Henry Blake Fuller, Charles Chesnutt, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Sarah Orne Jewett, Ambrose Bierce, Lafcadio Hearn … hmm, quite an era! (I’m not a Henry James fan, sorry. I am still waiting for the English translation of The Golden Bowl).

To make life easy for anyone seeking to list the major visual work of the day, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago Exposition included a sumptuous collection of the best American art of the day, with contributions by Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, Winslow Homer, and James McNeill Whistler, among a great many others. The organizers wanted to demonstrate that the United States was enjoying something like a cultural golden age, and they were not far wrong. And that does not include the cartoonists, caricaturists, and graphic artists who were flourishing in these same years, and about whom I have posted at this site. Overall, the visual resources for any study of the era are stunning.

What I have to say today is far more than I can cover in one blogpost, so this will be the start of an indefinite series. As I develop the topic, I almost certainly am sketching a whole new book project, but that remains to be planned out in any detail. What I do already know is that the material, both textual and visual, is overwhelmingly rich.

1893 matters.

The World Exposition

Because it has been so widely covered, I will say little here about that crucial Parliament of Religions, given that its importance is so obvious to be highlighted yet again here. The original records of the event and the proceedings constitute an inexhaustible resources.

In 1893, briefly, Chicago was the setting for the World’s Columbian Exposition, a spectacular world fair that commemorated the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the New World in 1492, and the commencement of European empire in that region. Throughout the year, all the world’s roads seemed to converge on Chicago, and that Exposition is likewise the subject of many books.

In associated with the Exposition, the World’s Parliament of Religions likewise met in 1893, including representatives of all the great faith traditions. It was in fact the first global interfaith gathering ever to be organized.

The organizers had no doubt of the superiority of their own Protestant faith, and the meeting concluded with a joint recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, an act that they hoped would show the fundamental spiritual unity of all the creeds. Yet Lyman Abbott, one of the leading American Protestant clergy of the time, freely declared his openness to the wisdom that other faiths might offer:

We recognize the voice of God in all prophets and in all time. … We do not think that God has spoken only in Palestine and to the few in that narrow province. We do not think he has been vocal in Christendom and dumb everywhere else. No! We believe that he is a speaking God in all times and in all ages.

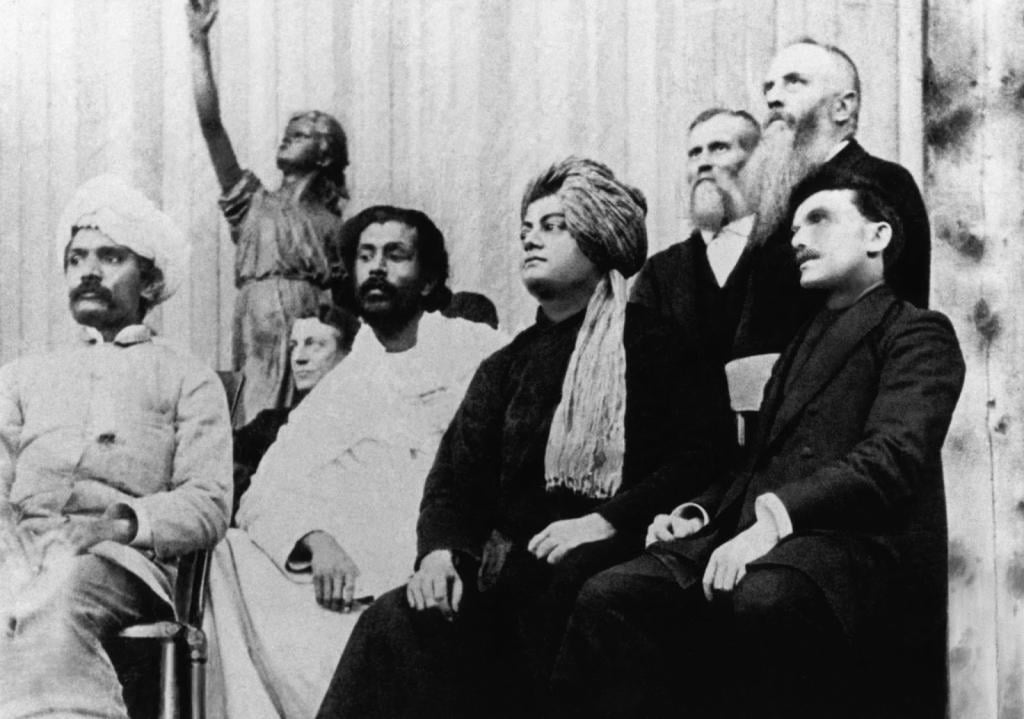

Certainly, Abbott then asserted the superiority of the Christian revelation, but for the time the openness to other faiths was remarkable. In practice, that Parliament opened the door for the enthusiastic white American exploration of Asian faith traditions, especially Buddhism and Hinduism, and Americans adopted many of the associated ideas, if (usually) stopping short of actual conversion. To appreciate the impact, we have to imagine a world in which the vast majority of Americans knew about Buddhists or Hindus only as those sad people described in the missionary tracts, who were just waiting to be illuminated by the newly arrived Presbyterian missionary from Iowa. Suddenly, those same Americans could see Asian gurus and spiritual masters in the flesh, and those “heathens” were deeply impressive.

Any history of that American exposure to global faith has to focus on 1893. Certainly the Transcendentalists like Emerson and Thoreau had been fascinated by Indian spirituality, but that subject now became a matter of mass public interest. Following the Parliament, the Hindu teacher Vivekananda was lionized as a celebrity, and the concept of the guru now entered American life. So did Vedanta mysticism, and the idea of yoga. D. T. Suzuki, the Japanese teacher of Zen, attended the Parliament, and his later influence would be enormous. Especially in California and western states, Asian religious ideas found expression in many new sects and – they already knew the word in its modern sense – of cults. It took a full generation for American culture to to absorb those insights, which they continued doing right through the “cult boom” of the 1920s. All the time, they kept harking back to 1893.

Writing shortly after the Exposition, Robert W. Chambers imagined writing a history of the United States from the near future world of 1920, and among the most important developments was this:

When, after the colossal Congress of Religions, bigotry and intolerance were laid in their graves, and kindness and charity began to draw warring sects together, many thought the millennium had arrived, at least in the new world, which, after all, is a world by itself.

I won’t go into this here, but those encounters also had their impact on the Asian societies from which those new ideas sprang. Suzuki himself was immersed in American Transcendentalism, which profoundly affected Zen traditions as they developed on both sides of the Pacific Ocean.

America the Beautiful

If it had just been the World’s Parliament of Religions, then 1893 would have marked a turning point in the history of American religion, but there was so much more. This was a truly visionary time, when all things seemed possible. In the words of the poem that Katharine Lee Bates composed in that very year, in the immediate aftermath of seeing the great “white city” of the Exposition:

O beautiful for patriot dream

That sees beyond the years

Thine alabaster cities gleam

Undimmed by human tears!

America! America!

God shed His grace on thee,

And crown thy good with brotherhood

From sea to shining sea!

Over the next twenty years, Bates had “given hundreds, perhaps thousands, of free permissions” for “America the Beautiful” to appear “in church hymnals and Sunday School song books of nearly all the denominations; . . . in a large number of regularly published song books, poetry readers, civic readers, patriotic readers . . . in manuals of hymns and prayers, and anthologies of patriotic prose and poetry . . . and in countless periodicals.” Because the poem so precisely captured the spirit of the age, it became nothing less than secular scripture.

And even after that, as the commercials say: but wait, there’s more! In my next two posts, I will talk about the revolutionary changes that now occurred in absorbing the findings of Higher Criticism into American Christianity; and also the deeply seditious insights of radical feminist criticism of the Bible, and of Christian history and tradition.