In my current project on the early 1890s, I have written a good deal about new religious ideas and movements, some of which were very influential. But religious issues, broadly defined, went far beyond the realm of heated discussion in parlors and seminaries, and contributed to making the years 1893-94 politically perilous, with serious threats of violence, and rip-roaring conspiracy theories. Time and again, anyone studying that era must be powerfully aware of the close parallels with the much better-known crises of the 1930s and the Depression era. In both eras, reasonable people feared outright revolution.

The whole era raises intriguing questions about how we tell the story of American history, and the lines we conventionally draw between “serious” protest and activist movements as opposed to conspiratorial groupings, and even “hate groups.”

Toward Crisis

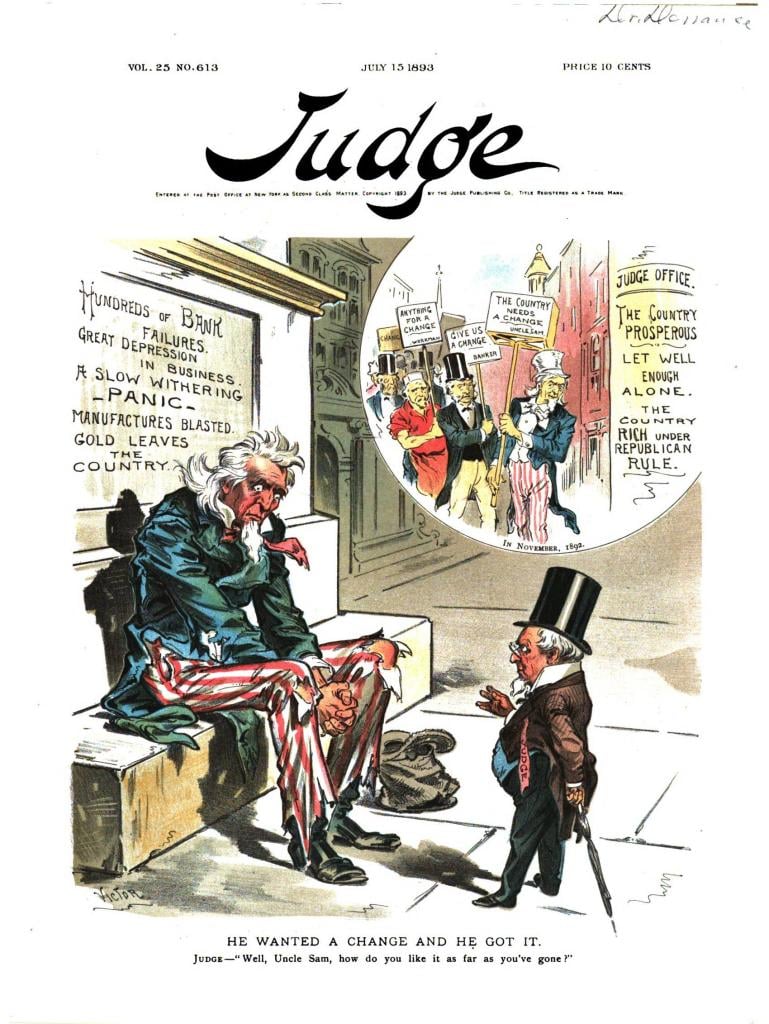

In 1892, the US elected Democrat Grover Cleveland as its president, choosing the man who had previously served from 1885 through 1889. Cleveland’s vice president bore the historic name of Adlai Stevenson, and he was reputed to be a ferocious radical. When Cleveland underwent dangerous surgery in July 1893, the matter was kept a dreadful secret because any prospect of Stevenson succeeding to the Presidency would have caused a financial panic: he terrified the rich. For maximum security, the surgeons carried out the operation on board a yacht sailing off Long Island.

The year 1893 began with high optimism, manifested in the spectacular World’s Columbian Exposition intended to commemorate the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World. Fittingly, the Exposition that opened in May was held in Chicago, that resounding symbol of modernity, and it was a cultural and technological extravaganza. The event suffered from some misfortunes that occurred at the time, including the assassination of the city’s mayor. But what the initial planners could not have known was that the year 1893 would mark a far-reaching economic crisis.

A stock market panic began in May – by a horrible irony, just two days away from the opening of the Chicago Exposition. By the end of 1893 the country was entering a deep depression that would last for four years. This was the most searing economic crisis in US history up to that point, and it remained the worst of its kind until 1929. I quote Wikipedia:

A stock market panic began in May – by a horrible irony, just two days away from the opening of the Chicago Exposition. By the end of 1893 the country was entering a deep depression that would last for four years. This was the most searing economic crisis in US history up to that point, and it remained the worst of its kind until 1929. I quote Wikipedia:

Five hundred banks closed, 15,000 businesses failed, and numerous farms ceased operation. The unemployment rate hit 25% in Pennsylvania, 35% in New York, and 43% in Michigan. Soup kitchens were opened to help feed the destitute. Facing starvation, people chopped wood, broke rocks, and sewed by hand with needle and thread in exchange for food. In some cases, women resorted to prostitution to feed their families.

The winter of 1893–4 was bleak, with perhaps 2.5 million unemployed and a total lack of social welfare facilities to begin to meet their needs. In the spring of 1894, some seventeen separate “armies” of unemployed marched on Washington DC to demand relief and reform, the best-known of which was named after its sponsor, Jacob Coxey. This was organized by the “Army of the Commonwealth in Christ,” but more generally known as Coxey’s Army. Protest also manifested in the Populist movement and the People’s Party.

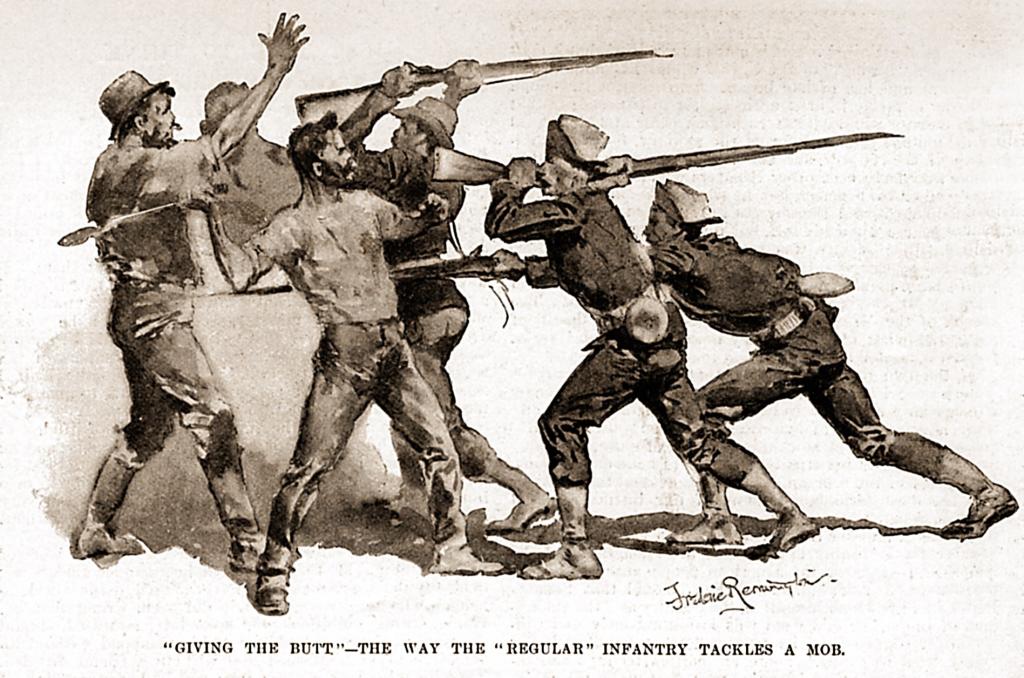

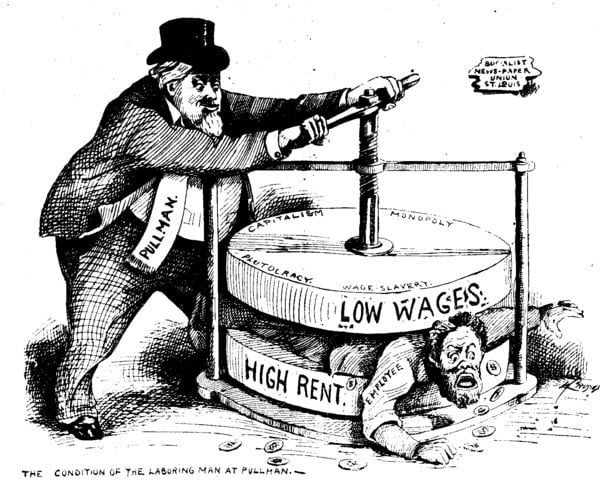

The increasingly militant labor unions fought the inevitable wage reductions, leading to some of the most savage industrial conflicts in the nation’s history. In 1892, the Homestead steel strike in Pennsylvania had witnessed epic battles between strikers and state militia, on a scale that looked much like a civil war. The movement was defeated, but unions revived in the harsh new environment. In Spring 1894, the Pullman strike in Chicago led to attempts to shut down rail traffic across the Midwest. The administration deployed the army to prevent such a devastating economic blow. At least seventy were killed. Between them, Homestead and Pullman remain the two most famous battle honors in American labor history.

The increasingly militant labor unions fought the inevitable wage reductions, leading to some of the most savage industrial conflicts in the nation’s history. In 1892, the Homestead steel strike in Pennsylvania had witnessed epic battles between strikers and state militia, on a scale that looked much like a civil war. The movement was defeated, but unions revived in the harsh new environment. In Spring 1894, the Pullman strike in Chicago led to attempts to shut down rail traffic across the Midwest. The administration deployed the army to prevent such a devastating economic blow. At least seventy were killed. Between them, Homestead and Pullman remain the two most famous battle honors in American labor history.

Democratic candidates suffered an electoral massacre in the 1894 Congressional elections, which opened the door to the crucial Republican triumph in 1896.

Religious Struggles

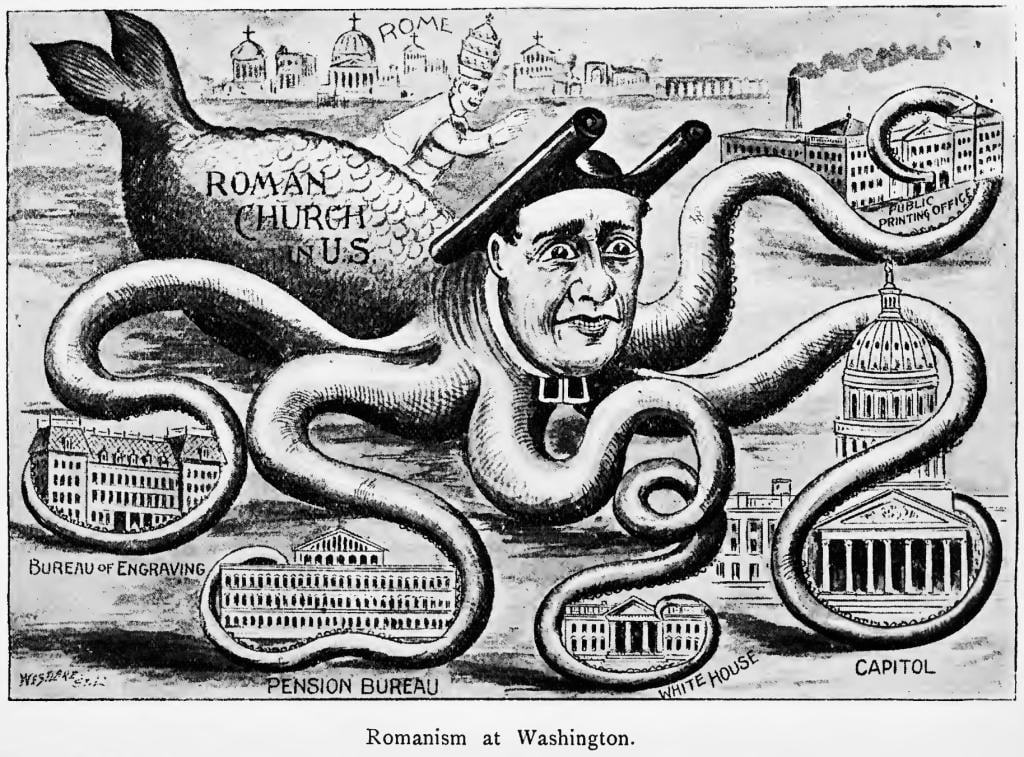

That story has often been told, but what we might miss is the potent religious movement that the crisis summoned forth. Since mid-century, the US had suffered from bitter Protestant-Catholic rivalries which at times threatened to erupt into overt violence. The early 1870s were such an era, when serious observers raised the prospect of a renewed civil war, but this time fought on religious lines.

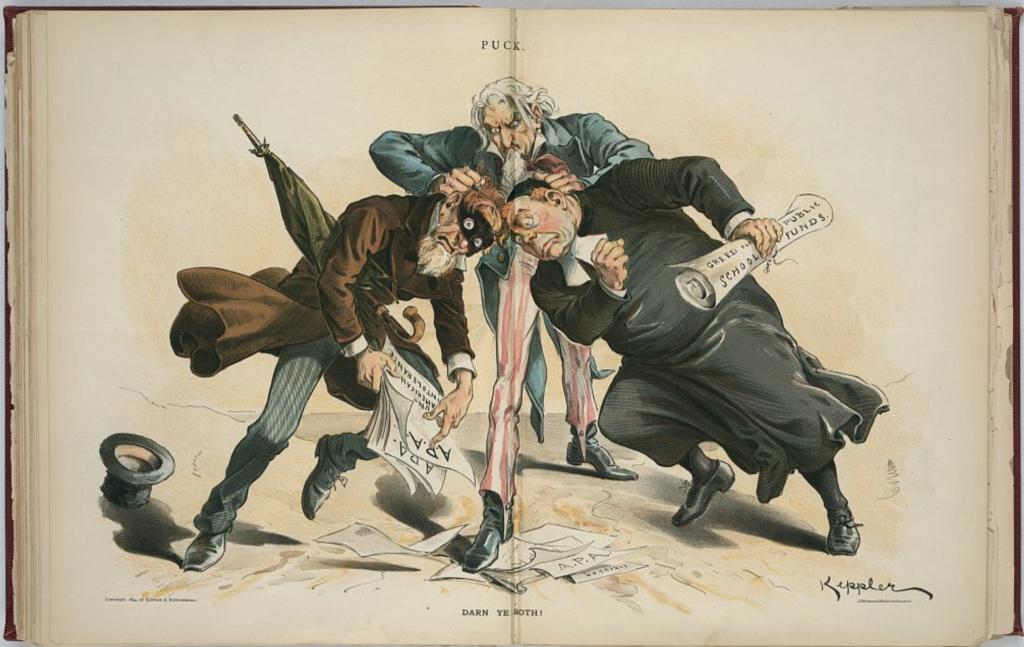

But if the hostility was not new to the 1890s, the sheer scale of the new movement in the 1890s was staggering. Founded in 1887, the American Protective Association (APA) began as a marginal grouping dedicated to defending Protestant interests against the machinations of Catholics, who supposedly followed secret directions dispatched by the Vatican. Allegedly, the Vatican planned the takeover of the US through armed insurgency, mainly directed by the Knights of Columbus. According to some accounts, the Catholic conspirators intended to massacre all heretics, a scheme proven by the many bogus documents then in circulation. These were over and above the very lively world of bogus confessions and exposés purporting to reveal the sexual depravity of priests and nuns. Self-described “ex-nuns” could count on a flourishing lecture circuit at this time, and for many years afterwards. On the Protestant side, the anti-Catholic “resistance” was largely a Masonic affair. The APA’s founder was Henry F. Bowers, a Freemason, who structured the movement on Masonic lines, with regalia, oaths and initiations. New members swore that

I do most solemnly promise and swear that I will always, to the utmost of my ability, labor, plead and wage a continuous warfare against ignorance and fanaticism; that I will use my utmost power to strike the shackles and chains of blind obedience to the Roman Catholic church from the hampered and bound consciences of a priest-ridden and church-oppressed people; that I will never allow any one, a member of the Roman Catholic church, to become a member of this order, I knowing him to be such; that I will use my influence to promote the interest of all Protestants everywhere in the world that I may be; that I will not employ a Roman Catholic in any capacity if I can procure the services of a Protestant.

The APA At Peak

As the economy sputtered and then collapsed, so APA membership surged. In early 1892, membership was a slim 11,000, but the group then passed the 100,000 limit by the end of 1893, and the boom continued. Notionally, the Vatican plan for a rising and massacre of Protestants was scheduled for September 1893, which must have focused the minds of potential recruits wonderfully; but the economic collapse undoubtedly attracted the discontented and terrified. People needed scapegoats and folk demons.

Also in 1893, the Vatican opened its Apostolic Delegation to the United States, under Cardinal Francesco Satolli, which to anti-Catholics looked like an attempt to set up some kind of Vatican provincial governor. Satolli was denounced as a would-be “American Pope.”

The APA dominated many states and cities across the Midwest. Aside from regular political offices, it was passionately involved in school board races, where the movement found one of its main causes in the defense of the public school against alleged Catholic subversion. Among the Association’s greatest nightmares was the prospect of public money being diverted to support sectarian (that is, Catholic) schools, which notoriously did not even used the correct Protestant-approved version of the Bible. To over-simplify a complex story, educational issues were usually at the heart of American Anti-Catholicism.

Our sense of accurate movement numbers is limited by the systematic tendency of APA leaders to exaggerate, and to go beyond actual paid members to report the supposed numbers of votes controlled in particular areas. By this standard, in early 1896, the group was reporting a voting strength of 3.5 million. Taking the different claims together, it is reasonable to suppose an actual card-carrying membership of around a million at peak in 1895-96. That is a deeply impressive figure if we think if it as a proportion of the population at the time – 63 million in 1890 rising to 76 million in 1900. APA membership then collapsed quite rapidly following the 1896 election.

In numerical terms alone, it is difficult to think of a more successful mass political movement in American history, and the obvious parallel is suggestive: this was the rabidly anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan of the mid 1920s, which might have hit five million members, albeit very briefly. The Klan likewise drew heavily on Masons and the other fraternal orders.

The World of Theron Ware

On this theme as in so much else of the religious world of the mid-1890s, there is a superb portrait in Harold Frederic’s novel The Damnation of Theron Ware (1896). The book tells the story of a naive young Methodist minister who meets some learned and educated people who transform his world view. Shockingly, one is a Catholic priest, an enlightened and liberal man, who is nothing like the monster of APA mythology. Theron Ware is forced to examine the dreadful images that shape his nightmare vision of Catholicism, and their complex historical roots. He examines the looming tableau forming in his mind:

The foundations upon which its dark bulk reared itself were ignorance, squalor, brutality and vice. Pigs wallowed in the mire before its base, and burrowing into this base were a myriad of narrow doors, each bearing the hateful sign of a saloon, and giving forth from its recesses of night the sounds of screams and curses. Above were sculptured rows of lowering, ape-like faces from Nast’s and Keppler’s cartoons, and out of these sprang into the vague upper gloom—on the one side, lamp-posts from which Negroes hung by the neck, and on the other gibbets for dynamiters and Molly Maguires, and between the two glowed a spectral picture of some black-robed, tonsured men, with leering satanic masks, making a bonfire of the Bible in the public schools.

That is a pretty fair picture of the APA’s vision, and how they constructed their enemies. Note by the way the “ape like” reference. Anti-Catholic caricatures of the time commonly depicted the Irish in particular as subhuman, which was exactly in keeping with the racial and criminological approaches of the time (I will return to this in a later post).

Telling the Story

Any college course on the Gilded Age or Progressive Era will devote huge attention to the Pullman Strike or the People’s Party, and their various counterparts, and local manifestations. The APA receives nothing like as much attention, despite its size and mass appeal.

As an intellectual exercise, just imagine that in the late nineteenth century, there had existed a liberal activist group dedicated to promoting civil rights or women’s rights, and that this had drawn a card-carrying membership close to a million from a wide area of the US – even if it was quite short lived. Let us call this imaginary group the American Progressive Association, the Other APA. I have no doubt in saying that the research on this group would be intense, from dissertations to major scholarly books, and that this research would now have a track record of half a century or more. We would have countless state- and city-level studies, biographies of every local leader, and detailed accounts of squabbles within local branches over issues of race or gender. The topic would be done to death as each new generation scrambled to find new and unexplored angles. Nothing vaguely like that exists for the Real APA.

The reason is simple enough: generally, we study what we like. We approve of heroic radical or civil rights group, while we hate the haters. The problem is that this approach means that we don’t pay nearly enough attention to some very important movements.

I offer a personal example. Back in the 1990s, I was very interested in social movements, which were and are the focus of a great deal of scholarly attention: How do they organize, how do they propagandize, to whom do they appeal, why do they rise and fall, how do they combine national and local activism? From all these points of view, I turned my attention to the Pro-Life movement which was then so active, and which integrated street activism with political agitation. To be clear, that interest did not reflect any ideological commitment on my part, it rather arose because of an objective realization that this was an important and under-studied movement. I was actually one of the few people to publish on anti-abortion terrorism, which was a terrifying phenomenon in the 1990s.

Around that time, I was chatting with a colleague who was then offering a course on Social Movements in American History, and described the various such groups I had studied. We got along fine. And then I mentioned the Pro-Life example, and suggested it might be a great topic for his course. Mere horror does not begin to describe his response. Obviously he would do no such thing. He would be studying feminist movements, civil rights movements, and gay rights activism, with all of which he was in total sympathy, and I am sure he would do an excellent job on all of them. But what about those other groups which were undoubtedly social movements driven by real passion? It seems they don’t exist. And if they do exist, they shouldn’t.

A subsequent conversation with another colleague about such movements introduced me to a common academic taxonomy of social movements. It seems that there are authentic ones derived from the grass roots, and then there are bogus ones generated by sinister interest groups to pretend they command mass support. These are not grass roots but rather “astroturf” movements, a term that dates from 1985. Further conversation revealed that my colleague viewed basically all left or liberal movements as “grass roots,” and thus authentic, while any and all conservative or reactionary counterparts were “astroturf.” To say the least, that is a convenient perspective, and one that carries a lot of weight in an academic world that leans heavily to the left and liberal.

Like I say, we tend to study what we like. And we shouldn’t do that, or at least we should not constrain ourselves thus. Bigotry needs its history too. Of course, this is no simple picture. Some unpopular groups definitely are the subject of a solid literature: just look at the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s. But generally, the point holds, and the (Real) APA is a prime exhibit.

The Wrong Adlai

One final note. In the dear dead days before cellphones and easy access to Google, I used to enjoy quizzing colleagues knowledgeable about American history with a simple question: When Adlai Stevenson was Vice-President, who served as President? They immediately supposed this was a trick question, as Adlai Stevenson had never held that office – or at least not the Adlai they knew well, who was the Democratic candidate for President in the 1950s. When I insisted I was right, people became increasingly confused and even annoyed, until I offered the simple solution, which was “Grover Cleveland.” The vice presidential Adlai was the grandfather of the liberal paladin of the Eisenhower years. Anyway, it used to be a fun riddle, which virtually nobody ever solved. Try it.