A couple of weeks ago, I had the great honor of participating in a symposium reflecting on the 60th anniversary of 1963 at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Institute at Stanford University. Over the course of several days, scholars shared their research on King’s legacy and impact, challenging modern mythologies of King and recapturing a radical message as relevant and necessary today as it was 60 years ago.

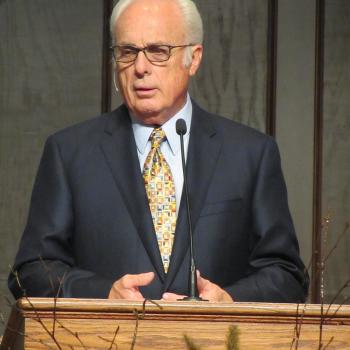

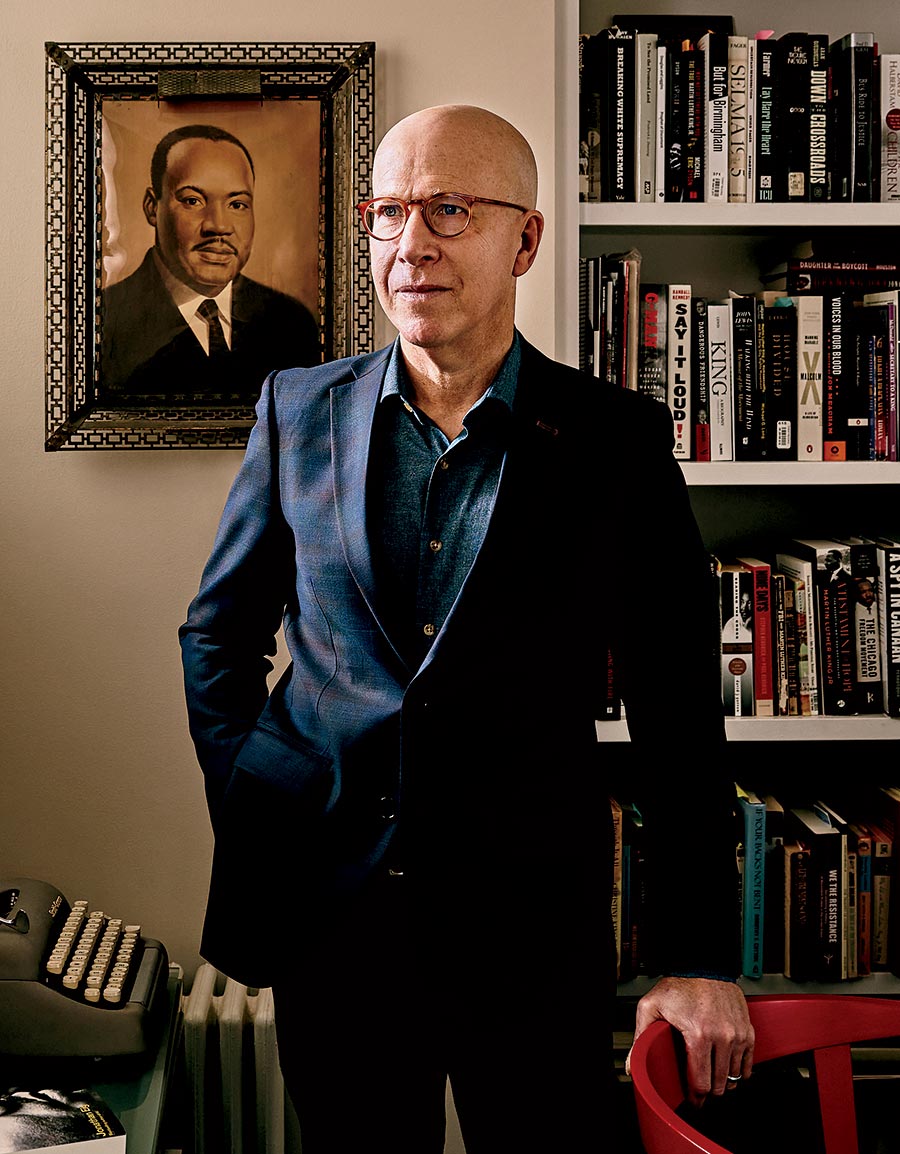

The event kicked off with a keynote address by journalist and King biographer Jonathan Eig. Having recently published King: A Life, Eig offered thoughts on King’s upbringing and marriage before turning to his role in 1963. King was, by that point, a “lightning rod,” Eig argued. He recounted the March on Washington, adding anecdotes, while noting that it was just two days later that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI targeted King, “the most dangerous Negro of the future.” Borrowing from Lerone Martin’s The Gospel of J. Edgar Hoover, Eig asserted that the FBI, threatened by King’s ability to galvanize a mass movement to change the American status quo, actually interpreted King and his radicalism correctly. That’s why they began to blackmail him over his infidelity, even encouraging him to end his life. King, for his part, reacted to the harassment generously, offering, “the Director must be under enormous pressure.” But so was King. Eig described a man pulled in many directions, unpopular, facing feelings of betrayal even by those close to him, but also a man insisting on going to Memphis and opposing the Vietnam War. Eig’s King had counted the cost. Movingly, he concluded with King’s words in the mountain top speech in Memphis, his almost pleading intonation that he just “wanted to do God’s will.” His last words, spoken the very next day to his driver’s encouragement that he grab a jacket were “OK, I will.”

(Photo by Jaclyn Rivas for Chicago Magazine; https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/may-2023/this-dreamer-cometh/)

Predictably, Eig is a fantastic storyteller, with a journalist’s sense of pacing and emotion. The Q & A was lively, including questions about the efficacy of nonviolence today, King’s improvisation, and also a perceptive question about the morality of using the FBIs records. Is it ethical for historians to use sources gained by intimidation and even slander?

The afternoon panel that day, “Why does 1963 matter today?” included brilliant, interdisciplinary talks from Jeanne Theoharis, Hajar Yazdija, Shirin Sinar, and Thomas Jackson each of which pushed against traditional narratives. Dr. Theoharis, a veritable encyclopedia of civil rights history, recounted King’s activism in the North in 1963, debunking traditional timelines and widening King’s activist scope. He demanded “All (rights), Here (wherever: LA, New York,, Birmingham), Now (1963), challenging segregation and pushing for a radical re-imagining of the status quo in the early 1960s, much to the chagrin of the Kennedy Administration. Then, Dr. Yazdija, author of The Struggle for the People’s King, eloquently explored the intentional misuses of King’s rhetoric in American politics from 1980-present. After explaining how King’s words had been used to oppose everything from affirmative action to Black Lives Matter, she concluded: “obstructing the past has been the political project all along.” Taking the conversation in a different, important direction, Sinar highlighted the federal surveillance and local enforcement against King and the post 9/11 surveillance “of structures and ideas, not just individuals.” Sinar explained FBI operations against vulnerable communities of color and who and what gets labeled “dangerous.” Finally, Dr. Jackson , author of From Civil Rights to Human Rights, concluded the panel with a detailed, expansive presentation on the Movement in 1963. Moving the emphasis away from King as a singular figure and towards the many local expressions and movements in 1963, Jackson employed archival footage, newspaper articles, and clips of speeches to show the varied expressions of a people’s desire for freedom. A wonderful discussion followed, including: what if King had not included the “dream” part of his March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom speech–would people have listened to the actual political and economic demands? Theoharis added that his reimagination was not simply a product of Reaganism but that “he was getting defanged as he’s alive” by media outlets. However, the conversation turned to possibility: with a King curriculum in every school, perhaps his radical reimagining of a just, beautiful America might be reintroduced?

After many ongoing conversations and a delicious shared meal, the conference resumed the following morning with a panel on the March on Washington. Jonathan Greenberg, Director of the Institute for Nonviolence and Social Change, offered moving remarks on the March of Washington and recalling the role of his long-time friend and collaborator (and Dr. King’s attorney) Clarence B. Jones. Greenberg detailed how Jones contributed to the speech and also highlighted the actual demands of the March on Washington, radical by any standards. (a $2.00 minimum wage in 1963 would be over $20 today). Again, we saw how King’s legacy and even his words have been watered down, where the political substance of his efforts was concrete, specific and quite progressive. Of course another of King’s demands, in the speech itself, was an end to police brutality–the subject of the next presentation by Dr. Ayesha Hardaway, Professor of Law at Case Western University. She broke down the legal maneuverings around injunctions against constitutional violations committed by police, showing how political Administrations skirt accountability and erode community trust. In the 1960s, police unions used their political and economic power to prevent community oversight, a practice that continues through weak consent decrees. Hardaway drew a direct line from the 1960s to the present day, something that Dr. William Jones, continued with his exploration of the March on Washington. Jones, author of The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, countered historiographical notions that the March failed, saying simply: “it worked.” It represented a massive protest with clear demands that made a demonstrable impact on policy. Jones explained that the March on Washington 1. was not a one-day event but represented decades of political organizing, 2. was led by institutions and organizations (especially Black women!) not personality-driven, and 3. was not moderate, but rather advanced a radical, wide agenda. The discussion centered around possibilities for such a broad coalition of institutions and clear agenda today, the current seemingly-renewed labor movement, and longing imaginings of a twenty dollar minimum wage.

The second panel of the day, coming after a leisurely break in the Palo Alto sunshine, considered the Birmingham campaign of 1963 and included Dr. Adam Banks, Dr. James Campbell, Jonathan Eig, and myself. Dr. Lerone Martin, the Institute’s Director, in his introduced the panel by reading a portion of a speech King gave at St. James Church in Birmingham on April 10, 1963 which is to be included in the forthcoming Vol. IIX of the King Papers Project. In the speech, King is encouraging the downtown boycott in unflinching terms, calling for sacrifice from the entire Black community for freedom. It was a poignant reminder of King’s power with words and his embodied commitment to the cause. Dr. Banks picked up the theme, discussing King’s rhetoric, how he “created a rhetorical situation where none exists, and celebrating Black creativity with words, from King to Black Twitter. Then, Dr. Campbell, who is currently working on a fascinating book about history and transmission and memory in Philadelphia, Mississippi, explored the 1963 moment in all of its depth and tragedy through David Dennis, Carolyn Goodman, and James Baldwin. Bringing in art, literature, and details of the movement in Mississippi, Campbell offered a wide ranging view of Black life and resistance in the period. Jonathan Eig then spoke, arguing that 1963 was King at his most effective. He told the story of Francine Yeager, who as a young Black girl in segregated Chicago, went to the March on Washington. She reported that the crowd was so big and King’s voice was so big and that “the spirit had captured…what a blessing.” This provided a nice segway for me to talk about religion in Birmingham in 1963. In a few minutes, I talked about Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and his Chrsitian nonviolence, about the religious motivations and lived theologies of ordinary Black Alabamians. I talked about white segregationists and their warped theologies of exclusion as well as the white moderates to whom King wrote so eloquently in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail. Finally, I talked about how the same forces of white Christian nationalism that defaced Jesus at the 16th Street Baptist Church and discouraged King with talk of patience and order are alive and well today. Countering them will take a bold theological reckoning with the radical demands Christ makes of his followers.

After the panel, some students asked since the church is gone (Stanford! Maybe it seems so) where the power might come from. What might replace the old Jesus ways? I tried to make the case that those who value racial justice should not concede the church, the language of morality and religion to the Right. That still matters, and we must make our case–our theological case–against the powers and principalities of white Christian nationalism.

Overall, the symposium left me brimming and inspired (and exhausted!). The collected scholars displayed an abundance of knowledge about King and the Movement as well as informed energy for applications of that historical insight. It was wonderful to connect with them as well as with the MLK Institute, which does such integral work on King’s life and legacy. Thanks for joining me in this summary from Palo Alto–wish I could as easily capture the lovely crisp air and sunshine!