“[T]here is no image of an American Indian intellectual” wrote the Lakota literary theorist Elizabeth Cook Lynn in 1996. She continues, “It is as though the American Indian has no intellectual voice with which to enter into America’s important dialogues… It is as though the American Indian does not exist except in faux history or corrupt myth.” This has been true also in literary circles.

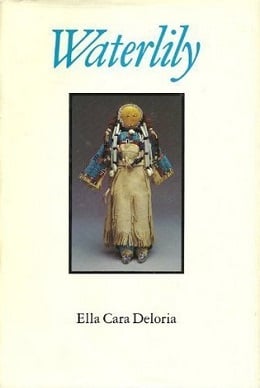

While studying for my comprehensive exams, I struggled to write here regularly, including missing my last couple posts here (Sorry Jake!). Having now passed my comprehensive exams, I promise to be on schedule with my posts from now on. To dive back in, I wanted to introduce y’all to perhaps the most unique book I read while studying for my comprehensive exams. This novel, part ethnography, part history, is a remarkable tale by one of the great American Indian intellectuals of the last century. It defamiliarizes the American West and Native Americans for almost any audience. Indeed, it is a novel the likes of which can probably never be written again. Its author was Ella Deloria.

Ella Cara Deloria was a member of one of the most notable Indigenous activist families of the twentieth century. (In fact, I have written about her nephew on this blog before.) Her family included the first Native American head of missions for the Episcopal Church (who quit out of frustration with the church’s racism), perhaps the most important Native activist of the second half of the 20th century, and an avant-garde artist.

Ella Cara Deloria was a member of one of the most notable Indigenous activist families of the twentieth century. (In fact, I have written about her nephew on this blog before.) Her family included the first Native American head of missions for the Episcopal Church (who quit out of frustration with the church’s racism), perhaps the most important Native activist of the second half of the 20th century, and an avant-garde artist.

After receiving a degree in physical education from (my own) Columbia University in 1915, she spent time teaching at the Haskell Indian Nations Boarding School before joining the anthropologist Franz Boas at Columbia as a researcher.

Waterlily is a novel researched in the 1920-30s, written in the 1940s, published in the 1980s, but set amongst the Teton Dakotas in the 1840s. In almost any other time, the novel would most likely not have been published for any number of reasons. Its uniqueness is as visceral as it is powerful. From the opening scene, a contemporary reader finds themselves in a world entirely different from their own. Not simply because it is set in another time, but also because of it is shaped by non-Western ways of knowing and social norms. The novel tells the story of two women across their lives. While under half the length Deloria originally planned and wrote, the story is still engrossing in both scope and depth.

Waterlily is deeply rooted in Dakota epistemology, ceremony, and kinship as ethics. Its narrative voice is ethnographically grounded but also intimately literary: interweaving cultural instruction with storytelling. The novel’s structure further reflects the rhythms of communal life: cyclical, relational, and morally coherent. There is a strong emphasis on the transmission of traditional knowledge, preserving cultural continuity, and modeling Indigenous womanhood in an unbroken connection of values and practices. Deloria’s work resists settler erasure not by dismantling narrative form as such, but rather by asserting a cohesive/coherent Dakota worldview through the novel—a hybrid genre she adapts to her own purposes. In this sense, Waterlily is an act of literary sovereignty, one that values stability, intergenerational transmission, and cultural persistence. Deloria insists that coherence is itself a political act in the face of colonial fragmentation.

Tiyóšpaye is a Siouxan term for the kinship based circle or spiral of tipis that form a Dakota camp while on the move. This term forms the basis for perhaps the novels most important theme, kinship. The theme comes with many questions, particularly, what does it mean to be good kin? This question reminds me that Cook Lynn and many other Native literary theorists often return to the idea that for Native people, “Taku inicia [Lakota: who are you?]” has never meant what is your name. instead, it asks Who are you in relation to the rest of us? It is a self-less question…” Instead, the self/person (I’m, reticent to use the word identity) is constructed reciprocally through kinship systems, community responsibilities, and cultural protocols. Waterlily the character, becomes a fully realized/recognized person by learning to navigate the ethical and ceremonial obligations of Dakota life which include marriage, mourning, generosity, and kin maintenance—instead of through asserting autonomy or property as in western equivalent cultures of the time. In this way, Deloria asserts a form of subjectivity that is sovereign without being state-dependent. This also mirrors Deloria’s own experiences with Boas and helps make sense of why Waterlily was never published in her lifetime.

Waterlily as a story predates the conditions of anti-Native racism. The novel tells a story from a perspective prior to white people. Euroamericans are only seen once from a distance, and the only consequences are when small pox appears in one of the Tiyóšpaye. Waterlily tells a radically different history. As Cook Lynn observes of the conflict between Euroamerican narratives of Native history as opposed to the stories we tell about ourselves: “it becomes a crime to revise a well-loved, scrupulously cleansed, and largely mindless history while the attempt to do better, to correct, to investigate is seen as inappropriate scholarship” Deloria is not engaged in a postmodern or postindian dialogue—because her story is not trying to reclaim Indigeneity from simulation; it never conceded it. The novel insists on Dakota presence without irony. Deloria claims the Western novel form as a vessel for Dakota knowledge systems, transforming a genre used for colonial narratives into a ceremonial text rooted in kinship, reciprocity, and moral instruction. Rather than focusing on resistance to colonialism, she describes/recreates an entirely Dakota-centered world: offering an inward gaze that refuses to translate itself for white readers. Her work acts as an alternative archive, preserving oral tradition, ceremony, and women’s roles in a time when assimilationist policies threatened and enacted their public erasure.

While Waterlilly is written in English and structured like a Western realist novel, it enacts Dakota ways of being in every narrative choice, from the structure of kinship ties to the moral weight of gift-giving. Additionally, the novel is didactic in a culturally embedded way it doesn’t simply tell a story, but instead teaches its readers what it looks like to live Dakota values. Deloria’s writing is layered with meanings that would be legible to Dakota readers, or to broader Indigenous communities familiar with ceremonial codes. It functions almost like a coded cultural document. The novel itself is a refusal of the nakedness colonial readers/experts expect from Native texts. There are no confessions, apologies, or trauma-driven appeals for help. Instead, the novel preserves cultural protocol and sacredness through narrative modesty.

While Waterlilly is written in English and structured like a Western realist novel, it enacts Dakota ways of being in every narrative choice, from the structure of kinship ties to the moral weight of gift-giving. Additionally, the novel is didactic in a culturally embedded way it doesn’t simply tell a story, but instead teaches its readers what it looks like to live Dakota values. Deloria’s writing is layered with meanings that would be legible to Dakota readers, or to broader Indigenous communities familiar with ceremonial codes. It functions almost like a coded cultural document. The novel itself is a refusal of the nakedness colonial readers/experts expect from Native texts. There are no confessions, apologies, or trauma-driven appeals for help. Instead, the novel preserves cultural protocol and sacredness through narrative modesty.

I don’t know if I will ever teach an American history class without assigning some part of this book. It is powerfully unique as a text in American history and literature. It tells a story of Native presence and experience essentially prior to meaningful contact with Euroamericans. I recognize that I haven’t explained any of the narrative or structure of the novel. This is on purpose. I don’t want to give anything away. This entirely other experience is something I want you to have for yourself.