This post concerns a book written some eight hundred years out of its proper time, and one with an evocative history.

Any acquaintance with early Christian history means encountering the many alternative gospels that circulated so widely in the first few centuries. Commonly, these works involved secret discourses and conversations that Jesus shared with his disciples, commonly after the crucifixion. Once the Roman Empire accepted Christianity, though, these works were destroyed or suppressed, and the common assumption is that they disappeared from view until their rediscovery in modern times. As I have suggested, that view is inaccurate, as different gospels remained available in various parts of the world.

Also contrary to the familiar stereotype, new pseudo-gospels actually continued to be written long after the fourth and fifth centuries, and some became widely influential. When we read them, we must be struck at how precisely they reproduce the format of those ancient lost gospels from centuries before, although they were written quite independently.

In the tenth century, a powerful Dualist movement called the Bogomils became very influential in the Balkans, in what was then the kingdom of Bulgaria. They became a whole alternative church with its distinctive rituals and hierarchy. Similar movements then flourished in Western Europe, until they were ruthlessly crushed by wars and persecution during the thirteenth century.

The Inquisition had a base of operations at Carcassonne in southern France, in the heart of what had been heretical territory. At the Inquisition’s archives, we find a manuscript introduced thus: “This is the secret book of the heretics of Concoreze [sic], brought from Bulgaria by their bishop Nazarius; full of errors.”

Now, this entry is multiply interesting: arguably, it is a historical novel waiting to be written. It describes a book written in Bulgaria, and stemming from the Bogomil church. This leaves no doubt about the wide international connections linking Europe’s Dualists during the High Middle Ages: clearly, heretics of Eastern and Western Europe really did see themselves as part of one common movement, one transnational church. The note also depicts a bishop of that church carrying that text to Concorezzo near Milan, in Italy. Although the work contains few internal clues to dating, it was probably written in the eleventh or twelfth centuries, presumably in Bulgarian. Conceivably, a Dualist congregation could have used it for decades before it was finally seized.

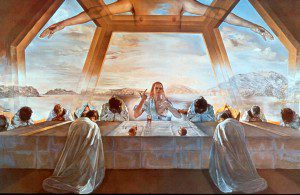

And it is a gospel, at least in the sense that this is the term we would assuredly apply if we discovered a similar text from the third or fourth centuries. Like those ancient scriptures, it presents distinctive views by putting them into Jesus’s own mouth, in the form of a dialogue with one of his apostles. Also resembling those early texts, it borrows an actual setting from the canonical gospels and uses that as the setting for an extended account. In this instance, the “secret book” reports the scene at the Last Supper when the apostle John lies upon Jesus’s breast. Hence the work’s alternative title, the Secret Supper.

The actual content of the “gospel” holds few surprises, as it is a classic summary of Dualist teaching. John begins his report with the words, “Lord, before Satan fell, in what glory abode he with thy Father?” Jesus then describes Satan’s former glory. After his Fall, Satan creates the material universe, in words that clearly echo those of Genesis, with Satan firmly identified as the God of the Old Testament. Satan, not God, creates humankind: “Then did the contriver of evil devise in his mind to make paradise, and he brought the man and woman into it. … the devil entered into a wicked serpent and seduced the angel that was in the form of the woman, and he wrought his lust with Eve in the Song of the serpent. And therefore are they called sons of the devil and sons of the serpent that do the lust of the devil their father, even unto the end of this world. And again the devil poured out upon the angel that was in Adam the poison of his lust, and it begetteth the sons of the serpent and the sons of the devil even unto the end of this world.”

John then asks, “How say men that Adam and Eve were created by God and set in paradise to keep the commandments of the Father, and were delivered unto death?” Jesus replies, “foolish men say thus in their deceitfulness that my Father made bodies of clay: but by the Holy Ghost made he all the powers of the heavens, and holy ones were found having bodies of clay because of their transgression, and therefore were delivered unto death.” Matter is death; the body is death.

From this Dualist standpoint, the whole history of the world is a story of Satanic deceit. It was the evil Enoch who inspired the practice of sacrifice. “Then did the devil proclaim unto [Moses] his godhead, and unto his people, and commanded a law to be given unto the children of Israel, and brought them out through the midst of the sea which was dried up.”

Liberation and salvation come only from the other God, the good God of Light, who intervenes to send Jesus – but assuredly not by putting him in the form of polluted matter: “When my Father thought to send me into the world, he sent his angel before me, by name Mary, to receive me. And I when I came down entered in by the ear and came forth by the ear.” Jesus’s followers must reject such evil inventions as baptism and the eucharist, which are Satanic snares.

In its format and the broad outline of its teachings, this is exactly the sort of text we might expect from the fourth century – yet here it is as a new creation of (probably) the twelfth. The Secret Supper must make us question the divisions we customarily draw between the worlds of early and medieval Christianity, and especially the unquestioning orthodoxy that we so normally assume in those later years.

Christians never ceased speculating about fundamental matters, and presented their conclusions by adapting and elaborating canonical texts.