I’m pleased to welcome David C. Kirkpatrick to the Anxious Bench. David is an assistant professor in the Department of Philosophy & Religion and Teaching Faculty in Latin American and Caribbean Studies at James Madison University. He is the author of the just-released A Gospel for the Poor: Global Social Christianity and the Latin American Evangelical Left. I was honored to blurb the book, and you should be able to tell that I’m a fan. I wrote, “Featuring impressive research in multiple languages, important historical recovery from the archives, theological nuance, and attention to context, A Gospel for the Poor captures perfectly the complexities of far-flung global evangelical relationships in the Cold War era.”

–David R. Swartz

***

Welcome to the Anxious Bench, David Kirkpatrick! Tell us about A Gospel for the Poor.

Let me begin by thanking you, David, for being such a careful reader and for your work that has inspired my own thinking. A Gospel for the Poor explores a renaissance of evangelical social Christianity. Why did many evangelicals in the Global North greet these ideas as family rather than foe in contrast to their reaction to the so-called Social Gospel of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

A Gospel for the Poor adopts a transnational perspective to tell the story of how a Cold War generation of progressive Latin Americans developed, named, and exported their version of social Christianity to an evolving coalition of global evangelicals. This broader transnational influence, while at times directly tied to progressive Latin Americans, often was mediated through mission and relief organizations such as Compassion International and World Vision. These organizations aggressively marketed their mission in conservative evangelical churches, magazines, radio stations, music festivals, and the homes of everyday evangelicals through pictures of “sponsored children” stuck to refrigerator doors.

Theologically, they no longer justified their presence exclusively through the language of evangelism or saving souls. Indeed, they shifted decisively in terms of what they were saving the world from—souls and bodies saved from eternal damnation and temporal suffering. They baptized their project as integral mission—dripping with the words and schema of the Latin American Evangelical Left. The book concludes with how global NGOs borrowed their language and framework, while rounding the political edge.

Long after the decline of the Evangelical Left as a political force in the United States, this new expression of social Christianity gained acceptance even among many evangelicals that rejected the political movement. The theological framework of many in a global Evangelical Left was built not within the American public square but within Cold War Latin America.

You are not the first to write about the topics of global Christianity, the Latin American Theological Fraternity, or Lausanne. What does this book add or change about older scholarship?

You are not the first to write about the topics of global Christianity, the Latin American Theological Fraternity, or Lausanne. What does this book add or change about older scholarship?

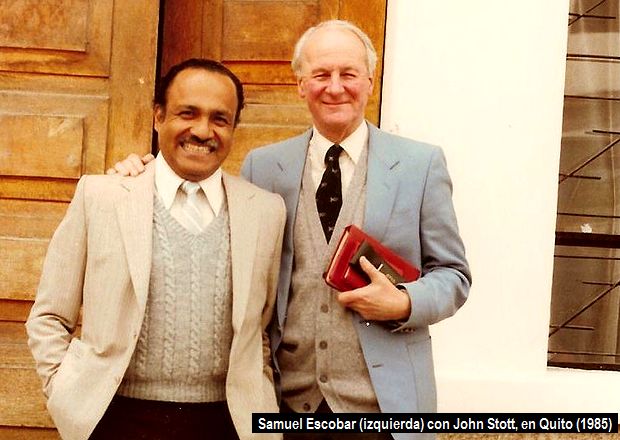

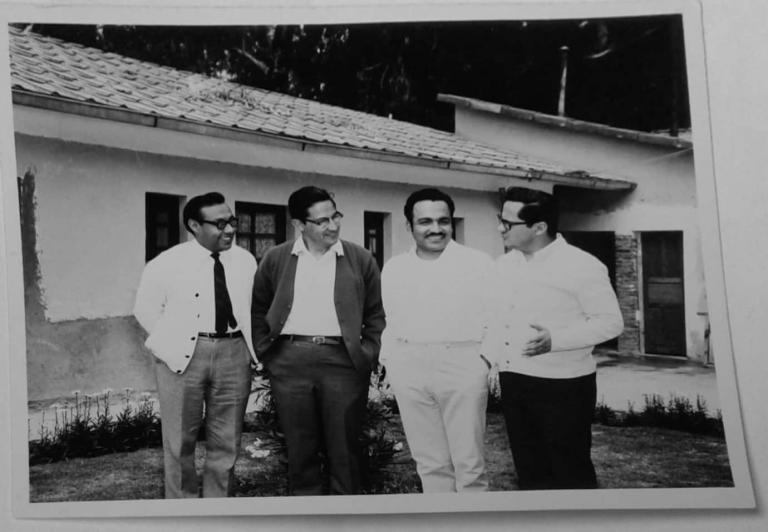

I sought to construct an alternative scaffolding for the Evangelical Left—one whose blueprint was not designed from centers of power but from the margins of the global Cold War. In order to do that, I utilized a far-flung set of archival materials from five countries—dusty boxes in René Padilla’s Buenos Aires garage, binders in Samuel Escobar’s Valencia, Spain, apartment, John Stott’s travel diary at Lambeth Palace library in London, and long-thought-lost meeting minutes from Seminario Bíblico in San José, Costa Rica, to name a few. I also had the privilege of conducting extensive bilingual interviews that flavor the narrative and fill in key details. By starting with an alternative archival base, I hoped to retell the story of the main Latin American characters but also a paint a revised picture of key powerbrokers such as John Stott, Billy Graham, and Stacey Woods, the founder of InterVarsity USA.

Let me give two brief examples. Woods, for example, destroyed all of his personal papers prior to his death. Yet many of his letters were carbon copied in the papers of my Latin American informants and include fascinating insight into his fraught relationship with Billy Graham, Campus Crusade founder Bill Bright, and his perspective on Lausanne 1974, among others events and people. Woods was instrumental in the rise of the Latin American Evangelical Left, as he released institutional leadership much earlier than rival organizations and provided space for their emerging social Christianity.

John Stott, whose only rival for influence during this time was Billy Graham, became intimate friends with René Padilla and Samuel Escobar during crucial years leading up to the Lausanne Congress of 1974. In particular, Stott’s travel diary records his extensive trips with Padilla in 1973, where they camped in the Patagonia mountains and stayed in the same hotel rooms while crisscrossing Latin America on a preaching tour to political prisoners and politically-engaged college students. Their friendship, it appears, was key not only to the social elements of the Lausanne Congress but also Stott’s very public conversion to social Christianity in 1975. Stott provided a stamp of approval to this Cold War social Christianity but also rounded its political edge. In the book, I explore ways in which Stott not only exported these ideas to the Global North but also has been falsely credited with the writings and contributions of Majority World thinkers. In some ways, the story of evangelical social Christianity has been whitewashed.

You use the term “Latin American evangelical left” to describe figures like Rene Padilla and Samuel Escobar. Who would you classify as being in the “Latin American religious right”? What have they been doing?

Most of Latin American Pentecostalism and evangelicalism would land rightward on the political spectrum. The recent Brazilian presidential election of Bolsonaro, often called the “Latin American Donald Trump,” presents a stereotypical example of the evangelical and Pentecostal voting bloc. This is partly why a story of a Latin American Evangelical Left is surprising, overlooked, and even thought impossible. Those familiar with Latin American social Christianity often think of Catholic liberation theology and its vast narratival shadow.

But the Latin American Evangelical Left came from the same context and same generation as many of those main characters like Gustavo Gutiérrez and even Pope Francis. Padilla’s successor Pedro Arana, whom I interviewed for the book, was a student in Gutiérrez’ Chimbote lectures that became his book famous Theology of Liberation (1971). This is simply one example where the proximity between Catholic and Protestant, Left and Right, were much closer than previously told. The Latin American Evangelical Left had to thread a needle between an overwhelmingly Catholic context. a rising Protestant right, and influential American missionaries in the region. This set the stage for fierce battles for theological and political turf.

What is the most difficult part of writing for you?

There is little more satisfying for me than the intellectual archaeology of archival research and oral interviews. I love encountering hidden stories and including diverse voices in new narratives. The most difficult part of writing, then, might be cutting material. I want the reader to know every intimate and gripping detail, and cutting them can be painful. I am thankful for editors (like Bob Lockhart at Penn) whose direction can help streamline narratives to better capture the story.